Rwandan Basketry 10

Rwanda on the globe

(licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported)

THE RWANDAN GENOCIDE: ANSWERING EXCRUCIATING QUESTIONS

- Perpetrators or génocidaires

In his must-read essay When Victims Become Killers, the Ugandan scholar Mahmood Mamdani recalled a political commissar in the army with whom he talked in July 1995. “When we captured Kigali – that man said – we thought we would face criminals in the state; instead, we faced a criminal population”.

“A criminal population”.

We already know that civilian participation in the genocide was particularly high, but is the expression used by that political commissar a simple hyperbole, an overstatement, a sally to impress interlocutors or there’s more? Is it possible to roughly estimate the number of génocidaires and perpetrators at least in the final phase?

Some scholars, like Mamdani, wrote of “hundreds of thousands” perpetrators but this figure is too rough and vague. Christian P. Scherrer, in particular, claimed that 40–66% of male Hutu farmers, 60–80% of the higher professions, and “almost 100%” of the civil servants participated in the final phase of the genocide (source: Christian Scherrer, Genocide and Crisis in Central Africa: Conflict Roots, Mass Violence, and Regional War, 2002). «If properly calculated – remarked Scott Straus – those numbers would total more than a million perpetrators». Is it too high?

The issue was handled by Scott Straus both in his How many perpetrators were there in the Rwandan genocide? An estimate (2004) and his later essay The Order of Genocide (2008).

First of all, he defined ‘perpetrator’ or ‘génocidaire’ as «any person who participated in an attack against a civilian in order to kill or to inflict serious injury on that civilian. Perpetrators, thus, would be those who directly killed or assaulted civilians and those who participated in groups that killed or assaulted civilians. (…). A perpetrator is someone who materially participated in the murder or attempted murder of a noncombatant» (Scott Straus, The Order of Genocide, cit.). This definition, referred specifically to the period from April 6 to July 19, 1994, includes those who participated in attacks against Hutus who resisted genocidal violence or were in the opposition. It includes, also, the members of the paramilitary militias that played a relevant role in the genocide – Interahamwe, Impuzamugambi, and to a lesser extent the Inkuba, ‘thunder’, the youth wing of the MDR party – and the members of Rwandan Armed Forces, Gendarmerie, Presidential Guard, and Local Police. In his works, Straus proposed a figure of 175,000 to 210,000 perpetrators. According to him, some 10,000 of the estimated 40,000 soldiers and militiamen played a direct role in the genocide; therefore, most of these 175,000 to 210,000 perpetrators were male civilians. This figure, supported by a complex analysis, corresponds to 14-17% of the active adult male Hutu population in 1994. It was a minority, there’s no doubt, but a relevant minority nonetheless, whose participation determined an exorbitant death toll.

The definition of ‘perpetrator’ or ‘génocidaire’ given by Scott Straus is somewhat imprecise. It does include only those who participated in a physical attack to murder, rape, or torture, using grenades, guns, panga machetes, impiri (clubs), swords, knives, fire (arson) and water (drowning), sticks, rocks, and even hands, at central congregation points (such as churches, schools, and government buildings), at roadblocks, during house-to-house searches or searches through cultivated fields, woods, and marshes. Does it include planners, organizers, instigators, supervisors, and fierce advocates of the genocide, namely all those hardliners who did not kill anyone and never took part in any physical attack but were nevertheless major criminals found guilty as génocidaires or accomplices to genocide and crimes against humanity by the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda?

The essay does not say a word on this issue, while a simple note in the article says that all of the latter are included in the given definition, which is not. Since it opened in 1995, the Tribunal has indicted only 93 individuals whom it considered responsible for serious violations of international humanitarian law committed in Rwanda in 1994. Therefore the number of the génocidaires who have never used a gun or a machete is a rather derisory one; the definition given by Scott Straus remains inaccurate nonetheless. On the other hand, his figure of 175,000 to 210,000 perpetrators is coherent with other data: we know that by 2000, the Rwandan government had arrested nearly 110,000 individuals on genocide charges, of whom about 6,000 had been sentenced by 2002. Most likely, a similar number of perpetrators managed to flee abroad, hidden among the mass of refugees.

Despite the inaccuracy of the perpetrator’s definitions, the analysis carried out by Scott Stuart is meticulous, acute, and fruitful. He found that «the overwhelming majority of perpetrators in rural areas were ordinary men. They were fathers, husbands, and farmers who had average levels of education and who had no prior history of violence» (S. Straus, The Order of Genocide, cit.). The massacres of Tutsis and almost all genocidal acts were forms of mass violence, committed by groups of people, often of considerable size, under the direction of local authorities, soldiers, or members of the rural elite. These men, the ‘average’ rural men chose to join groups of attackers for different reasons: for fear of being punished or ostracized, for concerns related to the advance of the RPF, for opportunism, and to get the chance of looting with impunity, under compulsion or forced by local authorities. «A small core of local actors seized the initiative, consolidated control, and then mobilized adult Hutu men to destroy the “Tutsi enemy” (…). A large number of genocide perpetrators had already complied with state orders to participate in unpaid labor before the genocide» (Ibidem). The traditional unpaid labor called umuganda, literally ‘coming together in common purpose to achieve an outcome’, became common immediately after independence in 1962, organized by central and local authorities. Umuganda was and is still perceived as the right individual contribution to community development. Scott Straus found that many average people joined the groups of attackers and took part in the massacres following the traditional umuganda ‘obligation’: they did the ‘community work’ they were told to do, as they and their fathers have done before, for decades.

Scott Stuart also found that «the younger perpetrators, those with fewer or no children, and those with lower levels of education tended to be the most violent during the genocide». He called them “the thugs”: «a small group of younger men or those who had firearms, (…), political party youths, angry young men, reservists, (…). They were local specialists in violence (..) and they did the lion’s share of killing» (Ibidem).

I will discuss both of these results by placing them in a wider context. For now, I’d like only to underline the convergence with some results by Lee Ann Fujii, Associate Professor of political science at the University of Toronto, author of Killing Neighbours: Webs of Violence in Rwanda (New York: Cornell University Press, 2011). She wrote that joiners, low-ranking implementers of the genocide, were «ordinary people, farmers, with no previous police or military training, married men with children» who do not fit the category of ‘loose molecules’, professional thugs or violence specialists, but whose actions are better explained through the power of local ties (quoted by Giorgià Donà in “Situated Bystandership” During and After the Rwandan Genocide, see Bibliography).

The following three pictures are part of a celebrated series shot by Greg Marinovich in the overcrowded Kigali prison in May 1995, featuring adults and teenagers accused of crimes against humanity and genocide. All photos are shown by courtesy of Greg.

The South African photographer and filmmaker Greg Marinovich (born in 1962) at the 2011 Tribeca Film Festival opening of The Bang Bang Club.

Photo licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported.

Scott Straus is not the only scholar who faced the problem of providing an estimate of the number of perpetrators in the Jenoside yakorewe abatutsi final phase. Jean-Paul Kimonyo, Rwandan director of the Levy Mwanawasa Centre for Democracy and Good Governance, an institution of the International Conference on the Great Lakes Region (ICGLR), developed a different approach. He and Christopher Kayumba wrote: «To have a clear picture, an estimate of the importance of the popular participation in the genocide is provided by the Gacaca jurisdictions» (Kimonyo and Kayumba, Bystanders to the Rwandan Conflict & Genocide: Current State of Research, 2008, see Bibliography).

Gacaca (please, pronounce it /gatchátcha/), or ‘justice on the grass’, «is a customary conflict resolution mechanism that existed in Rwandan society since pre-colonial times» (Door Bert Ingelaere, Inside Rwanda’s Gacaca Courts: Seeking Justice After Genocide, 2016, see Bibliography).

«Delivering justice for mass atrocities is a daunting challenge, and the scale and complexity of the genocide would have overwhelmed even the best-equipped judicial system. In Rwanda – where the justice system was under-resourced before the genocide – the task was made even more difficult because of the vast number of judges and other judicial staff killed during the genocide and the destruction of much of the country’s infrastructure. Tens of thousands of suspects were arrested after the genocide, often on the basis of a single unsubstantiated accusation of participation in the genocide. The number of detainees grew rapidly and quickly overwhelmed the prison system. (…) Extreme overcrowding and lack of sanitation, food, and medical care created conditions that were universally acknowledged to be inhumane and claimed thousands of lives. Many people were held for years without charge and without their cases being investigated. In December 1996 the government began to prosecute genocide suspects in conventional courts. By early 1998, only 1,292 persons had been judged and relatively few people had confessed to their crimes. The authorities realized that, at this rate, it would take decades to prosecute a large number of detainees. (…). The government then set up a commission to assess these problems and contemplate whether it would be possible to modernize the customary dispute resolution mechanism of Gacaca to enable it to handle genocide-related cases. (…). In June 2002, Vice-President Kagame officially launched Gacaca courts to try genocide-related cases and announced five core objectives:

- Reveal the truth about what happened;

- Accelerate genocide trials;

- Eradicate the culture of impunity;

- Reconcile Rwandans and reinforce their unity;

- Prove that Rwanda has the capacity to resolve its own problems»

(Human Rights Watch, Rwanda – Justice Compromised – The Legacy of Rwanda’s Community-Based Gacaca Courts, 2011).

Gacaca was therefore a traditional community court system, reshaped after the Genocide and aimed «at restoring the social fabric of society. It provides a means for survivors to learn the truth about the death of their relatives and for perpetrators to confess their crimes and seek forgiveness from their victims’ families, as well as their communities» (Genocide Archive of Rwanda).

BELOW

A Gacaca court in a village near Ruhango, 2005.

Photo by Lisa Rogoff / Advocacy Project, under Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 2.0 Generic (CC BY-NC-SA 2.0) license.

How a Gacaca court work is well shown by the following video, part of a 2010 film by Bengt P. Nilsson.

Let’s come back to Kimonyo and Kayumba: they estimate the numbers of perpetrators considering the Gacaca Jurisdiction’s data, and their definition of ‘perpetrator’ is different from the one adopted by Scott Straus.

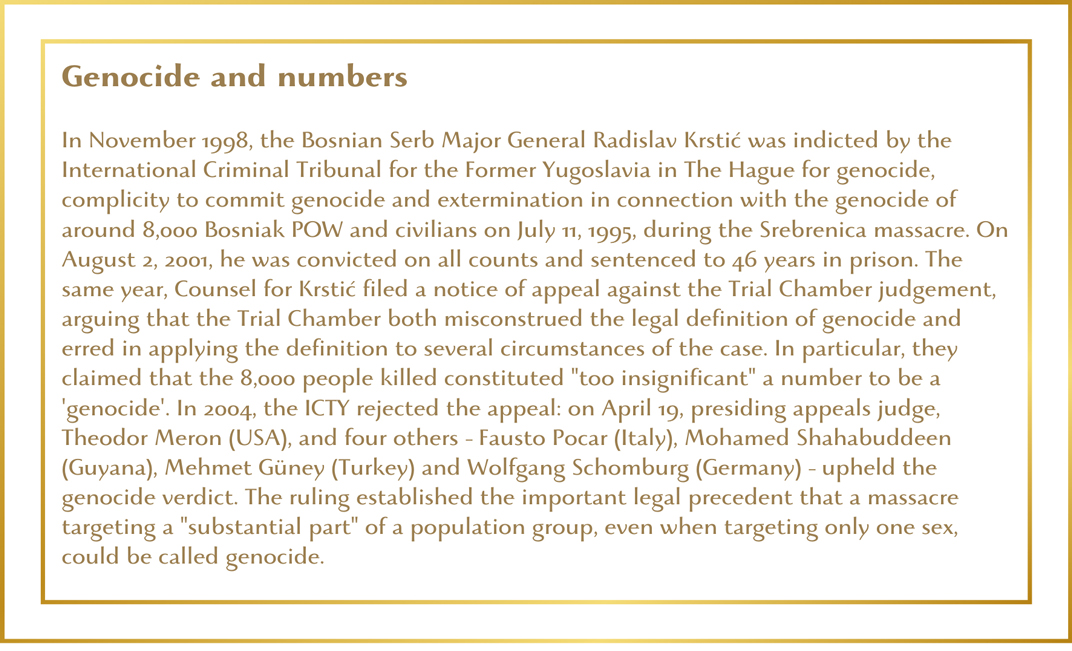

«These community-based and tradition-inspired tribunals – they wrote in 2008 – are responsible for the prosecution of people accused of involvement in the genocide. Almost at the end of their proceedings, Gacaca Jurisdictions issued some figures concerning the level of popular participation in the genocide. After the first phase of a formal gathering of information, Gacaca Jurisdictions have indicted 818,000 persons i.e. 11.4% of Rwandan population before the genocide, according to the 1991 population census, or 25% of the population aged between 15 and 54» (Ibidem).

The data quoted by Kimonyo and Kayumba are those given by the official report in July 2006 (Report on Collecting Data in Gacaca Courts, Kigali, National Service of the Gacaca Courts, 2006). However, the Gacaca court system was closed by President Paul Kagame in June 2012, and the final data are more impressive. According to an official report by the “Rwandan Service National des Juridictions Gacaca” and the data disclosed by the Fondation Hirondelle (a Swiss non-profit organization founded in 1995), there were 1,958,714 cases involving 1,003,227 individuals, most of whom were found guilty. The number of trials is higher than the people accused and sentenced because some of the latter were involved in more than one trial.

According to case statistics (different from individual statistics, where no data are available), 1,320,634 (67.5%) trials were related to looting and the destruction of property. 96% of people accused of these crimes, falling under the 3rd category, were found guilty. For the category of murder, torture, abuse, and physical violence (the 2nd one), a total of 577,528 cases were tried (29%); the acquittal rate of 37% was much higher than for property theft (only 4%). Finally, in the 1st category, that of organizers, authorities, and perpetrators of sexual violence, there were 60,552 cases tried (3.5%), with a 12% acquittal rate (source: Fondation Hirondelle). The number of the 1st category crimes is low because most were handled by ordinary courts, not by Gacaca ones. With regards to the latter, «there were prison sentences ranging from 5 to 10 years, life sentences in 5 to 8% of the verdicts and acquittals for 20 to 30%», said Justice Minister Tharcisse Karugarama (in office at the time).

There were criticisms and controversy surrounding the work of all Gacaca courts, an issue I cannot deal with here. I merely highlight that the Gacaca system developed a different categorization of ‘perpetrator’. Its final statistics, which have to be integrated with those given by the ordinary courts and the ICTR, gave us an estimate of perpetrators consistently different from that by Stuart Scott. Let’s do some math.

Straus gave a figure of 175,000 to 210,000 perpetrators. According to him, of the estimated 40,000 soldiers and militiamen in the country at the time of the genocide (which is a good figure, supported by other sources), some 10,000 played a direct role in the genocide, therefore the large majority of these 175,000 to 210,000 perpetrators were male civilians. He wrote: «My estimate of the number of perpetrators equals 7 to 8% of the active adult Hutu population and 14 to 17% of the active adult male Hutu population at the time of the genocide» (Scott Straus, The Order of Genocide, cit.). In a note, he says that «Rwanda had 2,813,232 citizens between 18 and 54 in 1991. If 8.4% were Tutsi, the Hutu population was 2,576,920, of which 48.7% were active men. Thus, the total number of active adult Hutu men was approximately 1,255,960. The actual figure may be slightly greater because of population growth between 1991 and 1994» (Ibidem).

The 8.4% data comes from the criticized Rwandan 1991 census, which probably under-reported Tutsis and over-reported Hutus. This means that the active adult Hutu male population in 1991 was less than 1,255,960. Marijke Verpoorten uses a more realistic 10.63%; in this case, if 10.63% were Tutsi, the Hutu population was 2,514,186, of which 48.7% were active men between 18 and 54. In 1991 we get 1,224,408. Let’s apply the growth rate of 2.5% (used by Verpoorten) to get an approximate figure for 1994: 1,255,018 adult active Hutu men.

Let’s now consider the Gacaca figure of 1,003,227 indicted. If we subtract the average acquittal rate of 25% (= 250,806), we get the figure of 752,421 convicts, to which we have to add the 93 sentenced by the ICTR and those judged by the ordinary courts in Rwanda. According to Human Rights Watch, at least 10,000 people have been tried for genocide-related crimes by conventional courts. Therefore, we can say that at least those convicted for genocide-related crimes were 762,514, setting aside those who fled from Rwanda to never come back. The large majority of the sentenced individuals were male, therefore we might say that this estimate approximately equals slightly less than 61% of the active adult Hutu population. Note that 61% is the lowest possible figure, not the highest, that’s to say that the real figure could be even bigger. In any case, it’s hugely different from the 14-17% proposed by Scott Straus. In other terms, in the spring of 1994, we face the participation in the genocidal violence of the majority of the Hutu adult male population.

Some people who were ‘bystanders’ for Stuart Scott were ‘perpetrators’ for the Gacaca system. None of the two included in the category of ‘perpetrators’ the supporters of the Jenoside yakorewe abatutsi: those who took part in night patrols (irondo) and surveillance tasks without killing or looting; those who reported the Tutsi families to the authorities; those who spat, mocked and humiliated the Tutsis forced on death marches; those who ate their cows with a light heart and heavy appetite; those who took part in the hunt of shocked Tutsi survivors hidden in the wood or the marshes; those who turned their faces away for a billion reasons; those who could have done something and instead did nothing and stood in a complicitous, criminal silence, like the official hierarchy of the Rwandan Catholic Church, for example.

During a genocide, the direct or indirect witnesses who do not take part in the massacres nor oppose them are called ‘bystanders to genocide’. They do not make up a homogeneous group, as we’ll see in the next chapter. In any case, in Rwanda, they were many. That of “a criminal population” is a boutade, a sally, but deep down, it rests on the bitter observation of a large mass of bystanders who were sympathizers, flankers, abettors, informants, bullies, but never killers.

- Perpetrators, victims, and bystanders to genocide: categories to be continuously rethought

That of ‘bystander’ is a problematic category, at least when referring to the Rwandan Genocide.

For Gacaca Jurisdiction, looters and pillagers were minor ‘perpetrators’, always criminals, not simple bystanders.

What about sympathizers, flankers, abettors, informants, bullies, and people who never killed or looted but supported the massacres with their behavior?

Are they complicit? I think so.

What about those who remained passive observers, closed their eyes, and turned away?

According to Ervin Staub, founding director of the doctoral program on the psychology of peace and violence at the University of Massachusetts Amherst and one of the most reputed experts on the topic, «this passivity directly or indirectly encourages perpetrators of violence and facilitates the evolution of greater harm-doing» (E. Staub, The Psychology of Good and Evil, see Bibliography). «The passivity and often at least some degree of complicity of bystanders make the perpetrators of violence believe that what they are doing is right» (E. Staub, Internal and External Bystanders: Their Passivity, Complicity, and Role in the Evolution of Violence, 2010, see Bibliography).

However, not all passive bystanders were equal in Rwanda: some of them did not adopt a consenting or compliant behavior; they simply remained silent for fear of being ostracized or even an object of retaliation, for receiving threats, for the inability to do anything to stop the genocidal violence, for powerlessness or dismay or distress. Many scholars, like Kimonyo and Kayumba, highlighted that at the time not being part of the killing machine was potentially dangerous and individually life-threatening: «not to participate was not always easy» (Kimonyo and Kayumba, cit.), given the intense pressure and the degree of psychological coercion and physical constraint exerted by the local authorities and rural elites.

The Italian scholar Giorgia Donà, author of the research paper “Situated Bystandership” During and After the Rwandan Genocide (see Bibliography), proposed to call “situated bystanders” the so-called ‘disapproving witnesses’ of the genocide, namely those who resisted the pressure to participate in genocidal violence and did not adhere to the hardliners’ im-moral horizon. «In a continuum between victims and perpetrators, might be positioned closer to the victims than the perpetrators» (G. Donà, ibidem). Therefore, «boundaries between bystanders and perpetrators or between bystanders and victims are often unclear and blurred and can change over time and across space» (G. Donà, ibidem).

For Giorgia Donà, these categories are not fixed, and the distinction between perpetrators, victims, bystanders, and rescuers is blurred. Moreover, they depict different behaviors, all situationally driven and therefore subject to change over time. I agree: bystanders can become perpetrators or rescuers, for example, and a minor who killed is a perpetrator and a victim at the same time.

I also agree with Donà’s criticism of the representation of the ‘morally guilty Hutu bystanders’, which is common nowadays in Rwanda. «The relevance of the culpability assumption was evident in post-genocide Rwanda when, at the launch of the Ndi Umunyarwanda (‘I am Rwandan’) campaign , President Kagame asked all Hutu to apologize for the crime committed in their name. (…) After the end of the genocide, the majority Hutu population were perceived to be either accomplices or supporters of the perpetrators or ‘passive’ bystanders who did not intervene to halt the violence or help the victims. The government’s request for a ‘Hutu apology’ exemplifies the view that Hutus are a homogenous group, collectively situated closer to the actions of the perpetrators than to the predicament of the victims. They are portrayed as passive bystanders who went along with the actions of the perpetrators, and did not resist the violence or help the victims. They are made to carry collectively the ‘moral’ guilt and shame of non-intervention» (Ibidem). This political view of Hutus as guilty bystanders has no historical legitimacy, especially since not only some «Hutus risked death by protecting Tutsi, but there are also many instances of Hutus who died to protect Tutsi» (Ibidem). Gérard Prunier wrote: «While some could be denounced and sent to their death by neighbors whom they had known all their lives, others could incredibly be saved by a kind-hearted Interahamwe! < it’s the case of the Interahamwe leader Yosia Pimapima on Nyabitaru Hill, near Kigali, who managed to save almost all the people on his hill>. Some people were denounced by their colleagues who wanted their jobs or killed by people who wanted their property, while others were saved by unknown Hutus disgusted by the violence» (G. Prunier, The Rwanda Crisis, cit.).

The following video, Zula, is part of a movie entitled A Song from Rwanda, directed by the Italian photographer Marco Barbieri. Zula tells the story of Zula or Zura Karuhimbi from Musamo, Ruhango District. In 1994, during the final phase, she saved the lives of 100 Tutsis, 50 Hutus and 2 Twas by hiding all of them in her home. She confronted the armed persecutors by exploiting her reputation as a traditional curator, believed to possess magical powers and something of a witch. Zula passed away in December 2018 at the age of 104.

The genocide was a complex process that placed the Rwandan population in such a morally complex situation that all easy-to-use generalizations sound seriously unjustified. To me, in the 1994 final phase, the Hutu bystanders, namely the large majority of the Hutu population at the time, cannot be held either morally guilty or innocent. Not adhering to the hardliners’ moral/immoral horizon did not entail adhering to “the moral world of ordinary, good-hearted people”, as claimed by Donà. Among the bystanders, we can find a broad range of moral, immoral, and amoral positions. Only a few Rwandans reacted to genocide by becoming helpers and rescuers, so the question is: why was there no critical mass to make up a levee or a barrier against the horror?

To answer this question, however, we must abandon a reductionist approach.

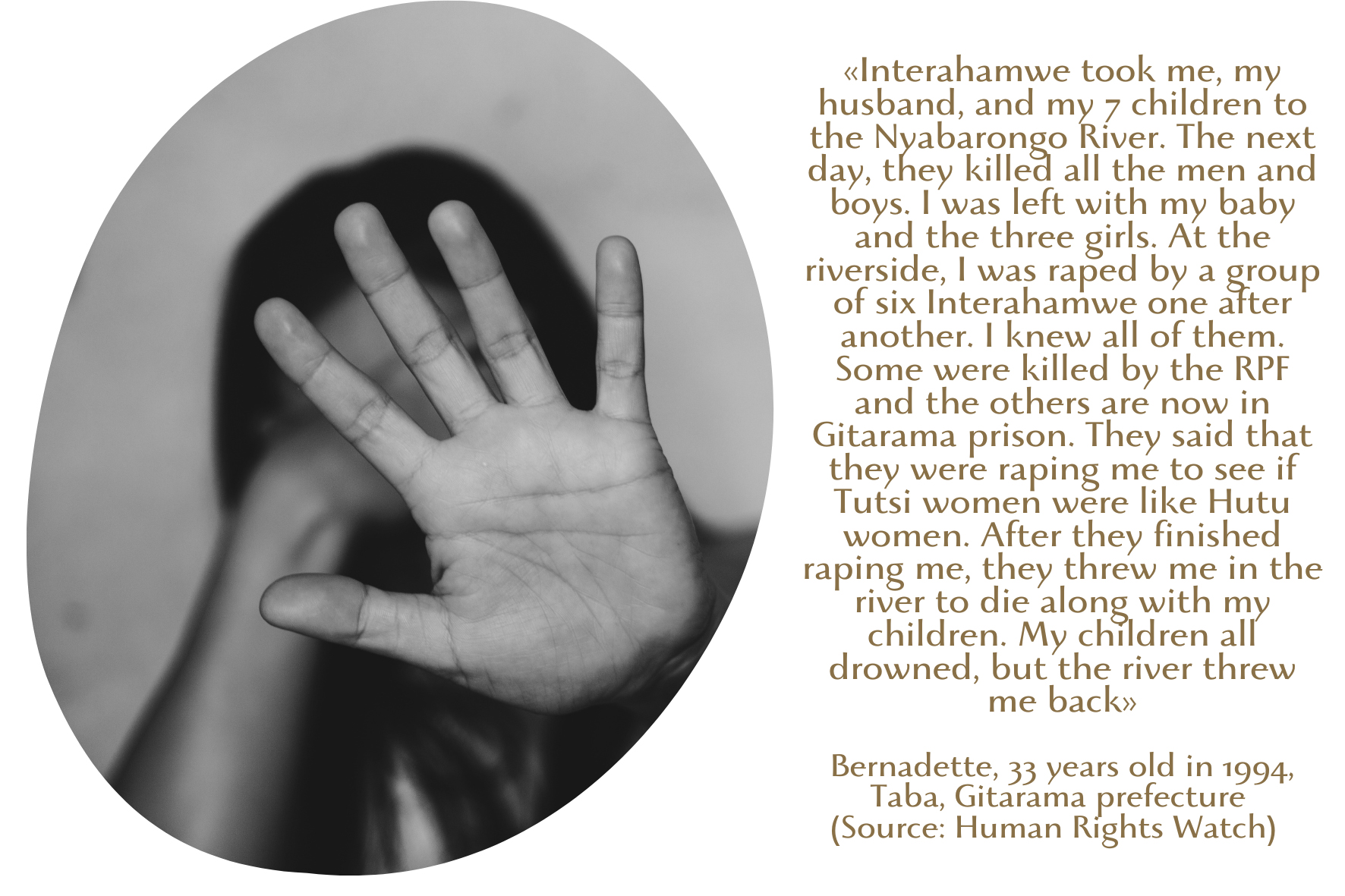

GIRLS, INTERRUPTED: SEXUAL VIOLENCE AND GENOCIDAL RAPE

«During the 1994 genocide, Rwandan women were subjected to sexual violence on a massive scale, perpetrated by members of the infamous Hutu militia groups known as the Interahamwe, by other civilians, and by soldiers of the Rwandan Armed Forces, including the Presidential Guard. Administrative, military, and political leaders at the national and local levels, as well as heads of militia, directed or encouraged both the killings and sexual violence to further their political goal: the destruction of the Tutsi as a group. They, therefore, bear responsibility for these abuses.

Although the exact number of women raped will never be known, testimonies from survivors confirm that rape was extremely widespread and that thousands of women were individually raped, gang-raped, raped with objects such as sharpened sticks or gun barrels, or held in sexual slavery (either collectively or through forced “marriage”) or sexually mutilated. These crimes were frequently part of a pattern in which Tutsi women were raped after they had witnessed the torture and killings of their relatives and the destruction and looting of their homes. According to witnesses, many women were killed immediately after being raped» (Human Rights Watch, Shattered Lives, see below and Bibliography).

According to one of the most extensive reports on the issue, Shattered Lives, Sexual Violence during the Rwandan Genocide and its Aftermath (edited by Human Rights Watch/Africa Human Rights Watch, Women’s Rights Project, Fédération Internationale des Ligues des Droits de l’Homme in 1996), it’s extremely difficult to give a solid figure as in Rwanda, rape was one of the most under-reported crimes for socio-cultural reasons (the victims of rape were stigmatized, marginalized, often rejected). «Although exact figures will never be known, testimonies from survivors confirm that rape was extremely widespread. Some observers believe that almost every woman and adolescent girl who survived the genocide was raped. While the ages of women and girls raped ranged from as young as 2 years old to over 50, most rapes were perpetrated against young women between the ages of 16 and 26» (Ibidem). According to many survivors and witnesses, the perpetrators (militiamen, soldiers, police officers, and civilians) frequently raped even corpses.

In the final phase of the Rwandan Genocide, the systematic rape of Tutsi women was not just a war crime, nor a crime against humanity, but an act of genocide, a ‘genocidal rape’. This term means that the rape was not a simple by-product of the civil war but an integral part of a systematic extermination campaign and an intentional strategy of genocide committed to destroy or undermine the reproductive capacity of the Tutsis as a population. «The pattern of sexual violence in Rwanda shows that acts of rape and sexual mutilation were not accessories to the killings, nor, for the most part, opportunistic assaults. Rather, according to the actions and statements of the perpetrators, as recalled by survivors, these acts were carried out with the aim of eradicating the Tutsis» (Ibidem).

During the final phase, women were gang raped, raped repeatedly with objects, mutilated, or tortured with outrageous, untellable brutality. «Some of these attacks left women so physically injured that they may never be able to bear children. Many victims of sexual assault died in the course of as a consequence of an attack. Sexual violence in such cases was a direct part of the killing. In other cases documented by Human Rights Watch/FIDH, women survived sexual violence because their assailants left them for dead, believing that they were mortally injured» (Shattered Lives, cit.).

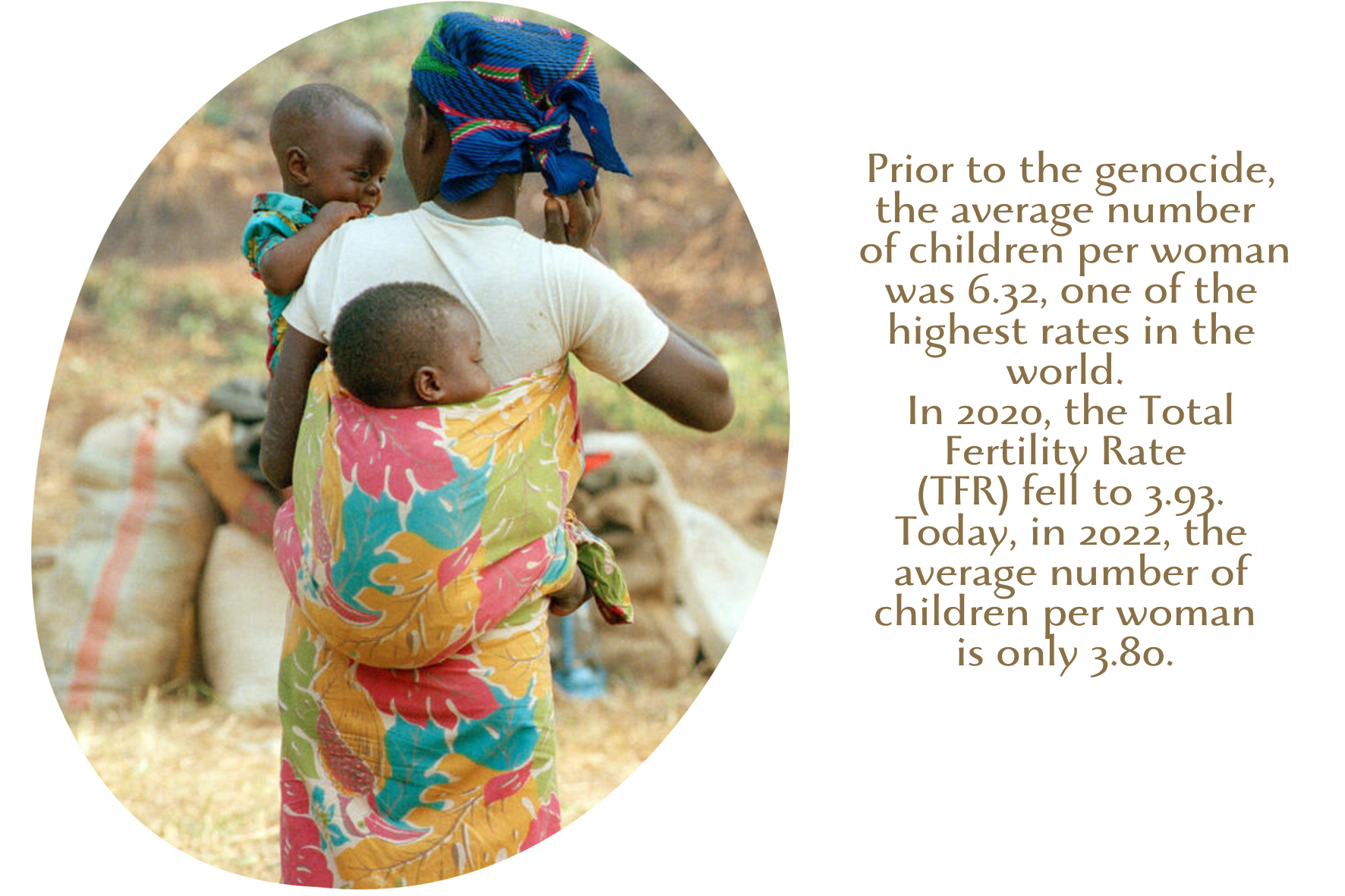

The systematic rape of women, organized and encouraged by military and political, local and national powers, produced in the aftermath both a generation of shocked and broken survivors, many of which tested-HIV positive, and thousands of ‘war babies’, ‘enfants non-desirés’ (unwanted children), ‘enfants de mauvais souvenir’ (children of bad memories), who were sometimes refused or abandoned (abortion was illegal in Rwanda, a country that partially amended the law only in 2012 to allow for induced abortion under certain circumstances). Note that in societies where lineage membership is determined via patrilineal parentage, as Rwanda, these children become members of the father’s and not the mother’s group. They are not only a permanent stigma and a public humiliation mark, but successful attempts to destroy the compactness of the group labeled as Tutsi.

This short story, entitled How a mother and daughter survived the pain of rape and genocide, filmed and reported by the journalists of The Washington Post, is worthwhile but includes some graphic scenes of the genocide (at the beginning) that you might find quite disturbing. The documentary shows the psycho-social difficulties of raising children born of rape in a country that did not allow abortion.

Jean-Paul Akayesu (1953) was a former teacher, a member of the MDR party, and the burgomaster of Taba (Gitarama prefecture) from 1993 to June 1994. (Do you remember Bernadette’s testimony? She was from Taba). Akayesu was arrested in Zambia 1995 and extradited. The International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda (ICTR) convicted him of using rape as a weapon of genocide even though he did not participate in sexual violence (he merely ordered others to rape and engage in sexual violence). He stood trial for 15 counts of genocide, crimes against humanity, and genocidal rape. On October 2, 1998, he was sentenced to life imprisonment. Please note that rape was declared a war crime in 1919 but was not tried in court until the Akayesu case in 1997, that’s why this trial was so relevant. Its story is told by a 2015 film documentary, The Uncondemned, produced by Film at Eleven Media and co-directed by Michele Mitchell and Nick Louvel. Below is the trailer of the documentary, which is absolutely worth your time.

Jean-Paul Akayesu (1953), burgomaster of Taba, in the Gitarama prefecture, from 1993 to June 1994.

The trailer of the 2015 film documentary, The Uncondemned, produced by Film at Eleven Media and co-directed by Michele Mitchell and Nick Louvel.

The Tutsi women were not the sole victim of rape: many Hutu women – wives of Tutsis, Hutu political opponents, and sometimes even passers-by – were gang raped. During the orgy of violence, «women were targeted, regardless of their ethnicity or political affiliation» (Shattered Lives, cit.).

Jennie E. Burnet, sociocultural anthropologist, professor of Anthropology and director of the Institute for Women’s, Gender, and Sexuality Studies at Georgia State University in Atlanta (US) wrote: «Sexual violence in the genocide ranged beyond ethnic/racial dyads of Tutsi-victim and Hutu-perpetrator. Many Hutu women and girls also endured sexual violence in 1994, and an unknown number of women and girls of all ethnicities were pressured into sexual relationships with soldiers after they reached the safety of internally displaced person camps in territory held by the Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF). Focusing solely on sexual violence committed by Hutu perpetrators against Tutsi victims obscures the complexity of sexual violence, sexual agency, and militarized sex during conflict» (Rape as a Weapon of Genocide, see Bibliography).

Jennie Burnet is one of the few who saw the complexity of sexual violence during the final phase and tried to address the issue by looking into the pre-genocide socio-cultural situation: «Long before the 1994 genocide, Rwandan women and girls faced a great deal of gender violence, including physical violence (such as domestic abuse and sexual assault) and structural violence (such as gender discrimination)» (Ibidem).

Precolonial Rwanda was a patriarchal society.

«Patrilineages were the fundamental structuring element of society (…) <and> operated as corporations that managed the economic and social well-being of its members, whether male or female. Widows, married women, and unmarried girls derived their social identities and rights to land from their male kin. A Rwandan proverb states Abagore ntibafite ubwoko, ‘Wives have no identity’, meaning that an unmarried girl has the same identity as her father or brothers, and a wife takes on the identity of her husband and his patrilineage. In short, a woman’s membership in a lineage defined who she was as a social person)» (Ibidem).

During colonial times, the patriarchal grip on women hardened both for the general tightening up of social structures and for the dominant Catholic education that valued women only as meek, docile wives and prolific mothers.

Moreover, «the colonial period brought many changes in Rwandan gender roles as the economy became monetized and the colonial state pushed husbands and men into the cash economy. These changes weakened the customary powers and rights of daughters and wives and increased the patriarchal nature of Rwandan society» (Ibidem). Female labor continued to be at the center of Rwandan agricultural production as it was in the pre-colonial period, but in the colonial time, the women were largely excluded from nonagricultural, salaried work.

Both in colonial and post-colonial times, the Rwandan woman had to be fertile, hard-working (as she had to carry out agricultural work, all kinds of housework, and childcare), and she was conditioned to maintain a modest, reserved, unassertive, and submissive behavior.

Butare, Southern Rwanda, 2012.

Photo by Thomas Stellmach, under Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 2.0 Generic (CC BY-NC 2.0) license.

Woman with hoe and child on her back, Kinyababa, Northern Province, Rwanda, 2011.

Photo by Adam Cohn, under Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 2.0 Generic (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0) license.

Both during the First and the Second Republic, under Kaybanda’s iron fist before and Habyarimana’s after, the women of independent Rwanda lived in a subordinate status, in a condition of legal minority: they were denied land ownership and access to opportunity outside the home; they needed the signature of their husbands to open a bank account and a man’s protection or the express authorization of their husbands to open a small trade; rarely they could obtain credit or keep on studying (girls represented some 45% of students in primary school, while in secondary school male outnumbered girls 9 to 1, and in university 15 to 1); malnutrition among women was higher than among men. Rwandan women were not only discriminated against in systemic ways, formally and informally, in education, health, politics, and employment; they were also subjected to domestic abuse and constant degree of violence.

The 1995 Rwandan government report, edited after Genocide, «estimated that 1/5 of women were victims of domestic violence at the hands of their male partners» (HRW, Shattered Lives, cit.). It wasn’t a post-genocidal problem, of course: an old Rwandan proverb states that a woman who is not yet battered is not a real woman. Throughout the 20th century, domestic violence was so normalized to be perceived as a customary behavior and fully accepted as such. The same holds for structural violence: sexism, gender stereotypes, prejudice and discrimination, inequities in access to the country’s resources, etc., were commonly regarded as ordinary societal norms; very few women were aware of their rights as women and recognized women’s rights as fundamental human rights.

Sexual violence during the civil war and the Genocide «took place in a legal, political, historical, and cultural context of patriarchy and gender discrimination» (J.E. Burnet, Sexual Violence, Female Agencies, and Sexual Consent: Complexities of Sexual Violence in the 1994 Rwandan Genocide, see Bibliography). J.E. Burnet highlights two absolutely relevant facts (without explaining them, though). She wrote: «Sexual assaults on women and girls increased dramatically following the beginning of the civil war in 1990. While it is almost certain that rape and sexual violence existed before then, they were not widely recognized as problems, and women’s organizations did not mobilize on the issue».

Sexual crimes started to increase in 1990, not just for the beginning of the civil war and the Jenoside yakorewe abatutsi – rape was both a war and a genocidal tool – but also because of the aggressive and racist propaganda campaign with which, since the Fall of 1990, Habyarimana and the ruling elite created, criminalized, and dehumanized a public enemy.

An essential component of the hardliners’ ideology was the systematic degradation and abasement of Tutsi women and a general fascist depiction of Hutu women as honest and modest mothers of the Hutu race, conscientious patron saint of the hearth and home. Note that the abasement of Tutsi women was not an aim in itself as it was carried out to further humiliate the male Tutsi community.

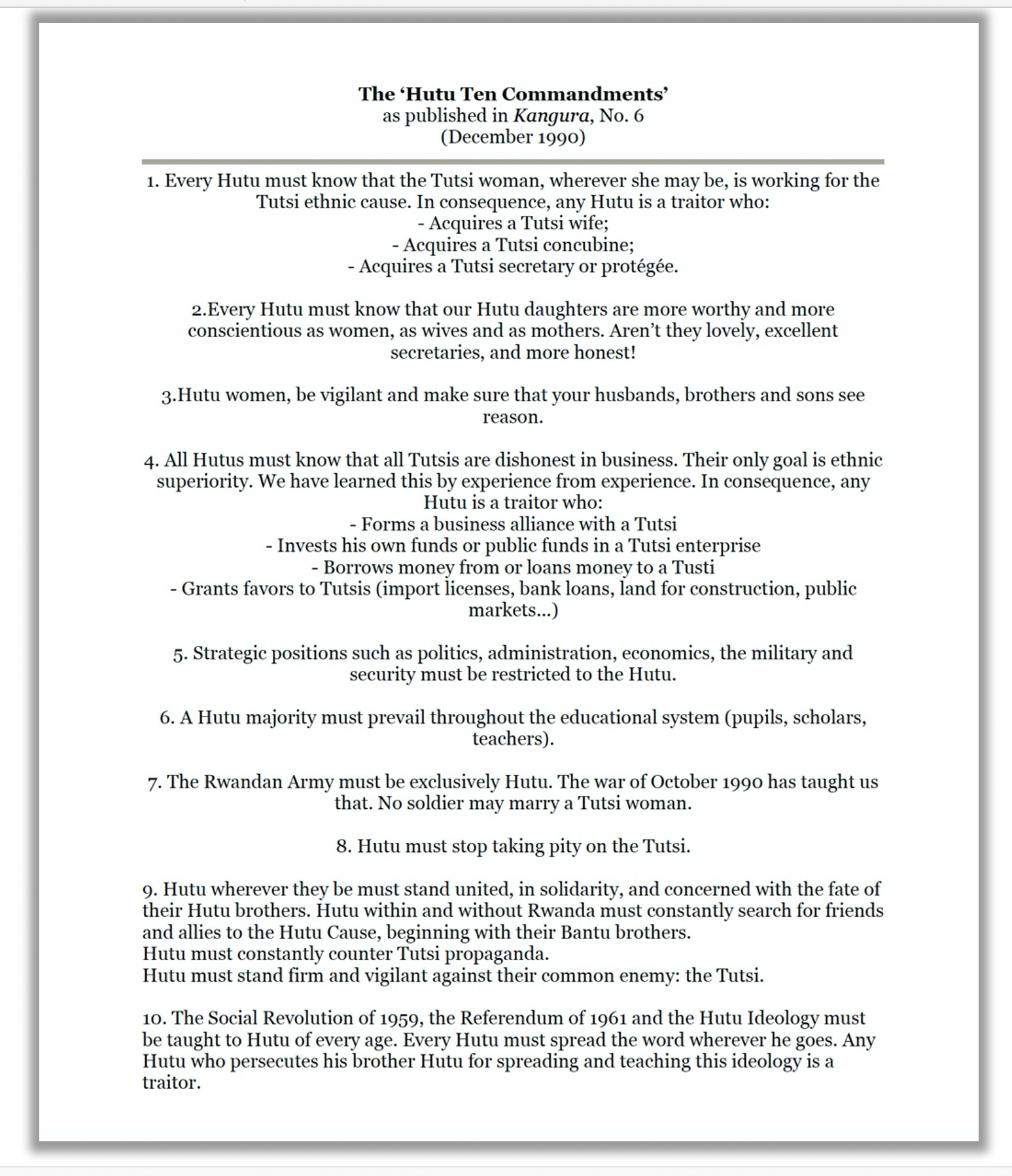

Do you remember Ngeze’s Hutu Ten Commandments? We analyzed part of the text in Rwandan Basketry 4. Let’s read it again.

Points 1 and 7. Tutsi women are wives, concubines, secretaries, and protégées – all subordinate roles in Rwanda – working for the Tutsi cause. They are disingenuous and masked enemies of all Hutus. They are women of ill repute. Wicked women. So bad that no soldier should marry one of them (or they would have to leave the military).

Points 2 and 3. Hutu women are ‘more honest’ and ‘more worthy’ wives, mothers, and daughters. They must take care of their husbands, brothers, and sons. Note that even if not clearly expressed or directly conveyed, these statements say that women, separated from their husbands, brothers, and sons, are nothing and are worth nothing. They must be vigilant as the Hutu spirit is willing, but the Hutu brothers’ flesh is weak, especially facing an attractive whore (Tutsi women were traditionally considered ibizungerezi, more beautiful, sexy, and promiscuous).

The general image of the woman that emerges from this text is not only imbued with the traditional Rwandan misogyny, but rests on a radical and extremely dangerous objectification: women are considered as functions of men to whom they ‘belong’, and treated as objects. The Tutsi women, in particular, are further depreciated as unworthy objects and treacherous tools in the hand of the enemy. A drastic objectification of women like that entails their violability. The labeling of the Tutsi women, and their categorization, so full of contempt and disdain, portends the legitimization of their rape.

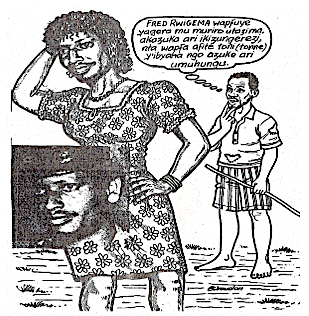

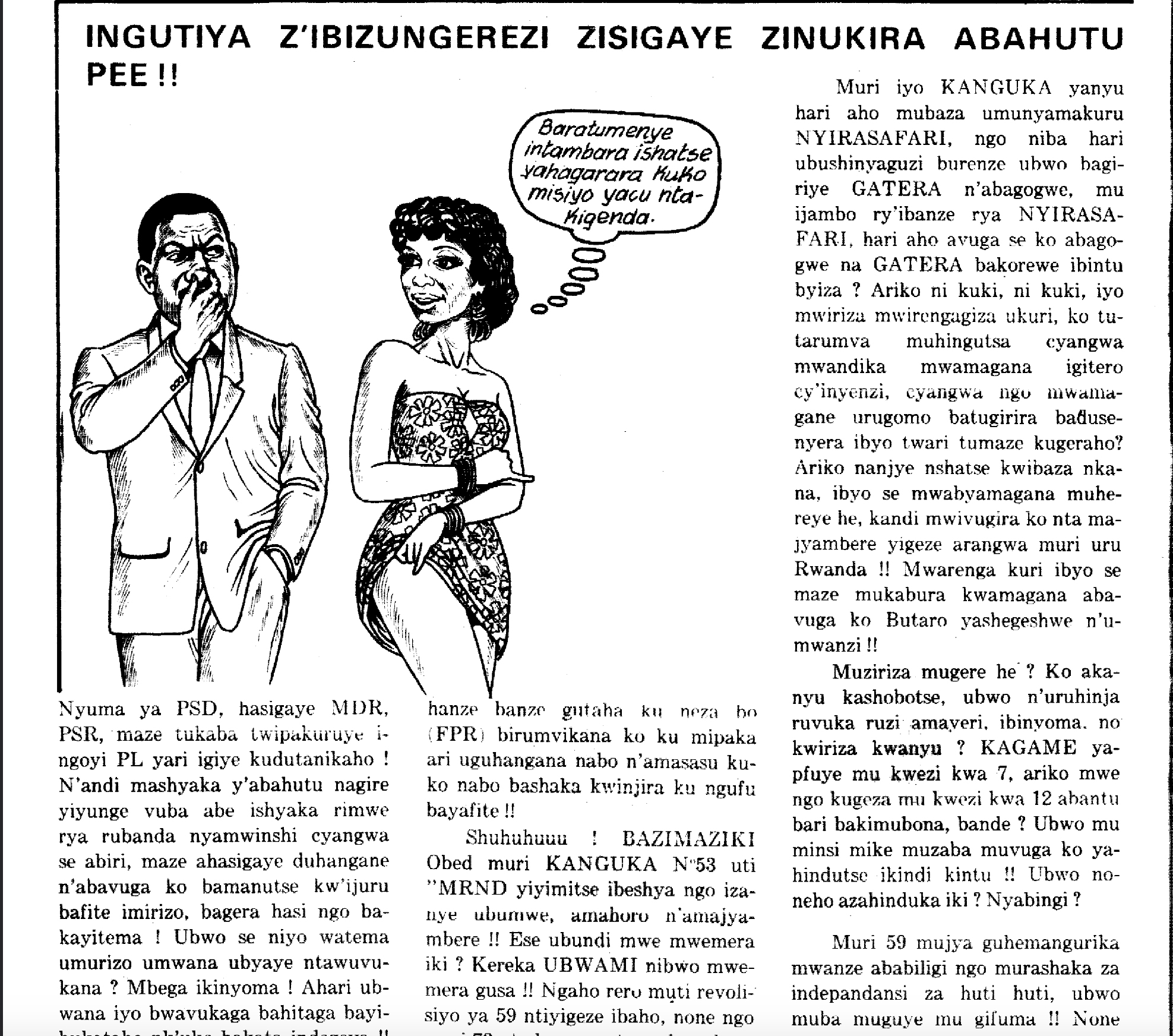

Ngeze’s Hutu Ten Commandments is no isolated case: the entire hardliners’ campaign was imbued with a systematic degradation of the female figure and of Tutsi women in particular. Look at the following cartoon: it was published in the hardliners’ magazine La Médaille Nyiramacibiri in October 1991. The Hutu peasant in the background (recognizable for his typical clothes) is looking at the beautiful woman in the foreground who shows the face of Fred Rwigema, the Tutsi military officer and founder of the Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF), killed on October 2, 1990. The peasant says: “Fred Rwigema died. He was burned by the fires of hell but he’s going to resuscitate under the form of an ikizungerezi (a beautiful and sexy Tutsi prostitute), as no one can die with so many sins and be reborn as a man (umuhungu)”. The inferiority of women is set off both in life and in the afterlife!

La Médaille Nyiramacibiri, issue no. 4, October 1991

The following cartoon was published on Kangura no. 35, May 1992. It illustrated an article telling how a Hutu man unmasked a Tutsi prostitute, ready to do anything for her “race”. In the cartoon, she says: “They told us that the war would stop because our mission is no longer going on”. He says: “Her underpants are starting to stink”.

Kangura, issue no. 35, May 1992

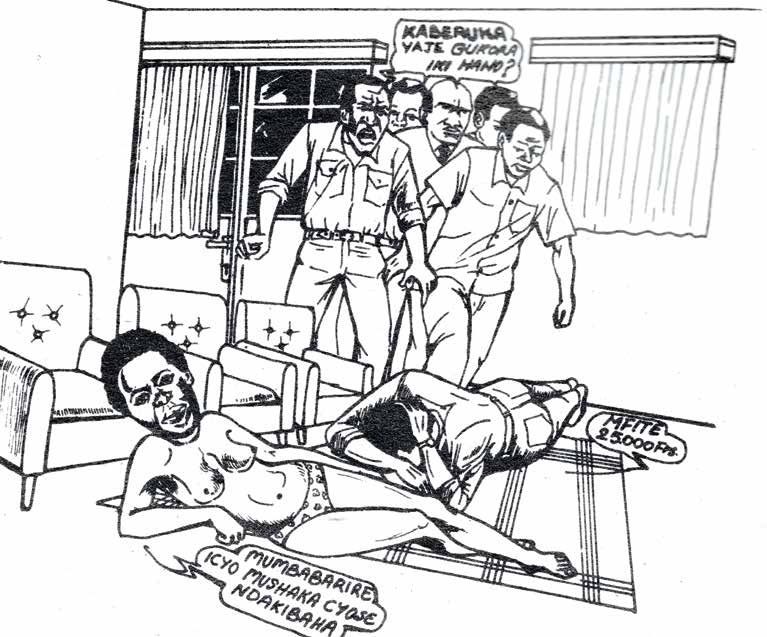

The next caricature from a 1992 issue of Kangura depicts Agathe Uwilingiyimana, the Hutu opposition politician who served as Prime Minister from July 1993 until her assassination on April 7, 1994. Some citizens surprise her naked on the floor, lying with her lover, and express all their anger for this offensive behavior. She says: “Forgive me, whatever you want, and I’ll give it to you”. Agathe Uwilingiyimana was one of the most recurrent target of the hardliners who portrayed her in the most degrading poses, often as a sexually promiscuous woman or under a dirty animal form. Do you remember the cartoon that depicted her as a sewer rat? On April 7, 1994, before being killed with her husband by the Presidential Guard, she was sexually assaulted, raped and tortured (a beer bottle had been shoved into her vagina).

Kangura, issue no. 36, May 1992

The last cartoon, from a 1994 issue of Kangura, depicts UNAMIR commander, General Roméo Dallaire, with some Tutsi prostitutes. The sentence in Kinyarwanda reads: “General Dallaire and his army have fallen into the trap of Tutsi ibizungerezi (beautiful and sexy Tutsi prostitutes).

Kangura, issue no. 56, February 1994

One of the most disturbing aspects of the genocidal campaign launched by the hardliners in 1990 is the fact that its violent, misogynistic content, which got even more obscene after mid-1993, faded into the background compared to the anti-Tutsi virulent ideological content. It was far less perceived. It received very little attention simply because the country was already inured to some degree of gender-based violence, misogyny, and gender discrimination.

The hardliners’ campaign, which radicalized and brought the debasement of the female figure to the extreme consequences, the systemic subordination of Rwandan women, their second-class status in society, the gender inequality, and the social normalization of gender-based violence not only made Rwandan women much more vulnerable and defenseless against all kinds of sexual crimes during the Genocide but also made rape a much more ordinary and widespread behavior, fueled sexual sadism and pushed sexual atrocities beyond the limits known until then.

In Rwanda, the normalized gender-based crimes and the traditional structural violence funneled into the racial violence, pushed by the hardliners’ political approach that racialized all kinds of social tensions, and acted on the genocidal massacres just like dangerous accelerants spread on fire: they speeded up its development, escalation, and intensity.

Mother and Child at the “Village of Hope” Rwanda Women’s Network community center, an initiative to provide services and emergency housing to women victims of rape and other violent crimes committed during the Rwandan Genocide. Kigali, January 29, 2008.

Photo: © UN by Eskinder Debebe

MORE ON THE COMPLEXITY OF GENOCIDAL VIOLENCE

The 1990-1994 Genocidal violence took place in a country that had been plagued by a very high rate of structural violence for much of the 20th century, at least since the 1920s. Structural violence is indirect harm imposed by a ruling elite (Belgian colonialists, Kaybanda’s regime, Habyarimana’s voracious elite in our case) on the mass population through a politically implemented socio-economic system.

«The harms may or may not be inflicted deliberately, and may occur without the clear awareness of the parties involved (…). A guerrilla in El Salvador explained the concept to an American volunteer physician this way:

You gringos are always worried about violence done with machine guns and machetes. But there is another kind of violence that you must be aware of, too. I used to work on the hacienda… My job was to take care of the dueño’s dogs. I gave them meat and bowls of milk, food that I couldn’t give my own family. When the dogs were sick, I took them to the veterinarian in Suchitot or San Salvador. When my children were sick, the dueño gave me his sympathy, but not medicine as they died. To watch your children die of sickness and hunger while you can do nothing is violence to the spirit. We have suffered that silently for too many years. Why aren’t you gringos concerned about that kind of violence? (source: Clements, 1984)» (George Kent, Structural Violence, see Bibliography).

«Notwithstanding positive macro-economic indicators, Rwanda has been characterized for decades by a high degree of structural violence; during the years prior to the genocide, this structural violence greatly intensified. This reality contrasted sharply with the dominant image of Rwanda, shared by donors and government officials alike, of a country in which development was proceeding nicely, under the capable leadership of a free-market-oriented government. Contrary to appearances, Rwanda was characterized by great inequality of both assets and income» (Peter Uvin, Development Aid and Structural Violence: The case of Rwanda, see Bibliography)

As we saw in the chapter The Immediate Background (in Rwandan Basketry 4), between the late 1980s and the beginning of the 90s, the ruling elite in Rwanda was a ‘thieving elite club’: many ministers, state employees, top administrators, and high-ranking officers among the most faithful to Habyarimana, bound to him by kinship and clannish ties, used access to preferential treatment to build profitable private businesses, while the destiny of the mass population was marked by extreme poverty, material deprivation, oppression, dramatic inequality, inequity, injustice. Clientelism, corruption, abuse of power and impunity on one side, racial and gender-based discrimination, denigration of the poorest, and social exclusion on the other. All these are forms of indirect structural violence.

«By the early 1990s, according to one analysis, 50% of Rwandans were extremely poor (incapable of feeding themselves decently), 40% were poor, 9% were non-poor and 1% – the political and business elite – were positively rich» (The Preventable Genocide, cit.). Even before the 1989-90 economic crisis and civil war, Rwanda was one of the world’s least-developed countries in Africa, and according to the United Nations Development Programme, it ranked below average of all of the sub-Saharan African countries in life expectancy, child survival, adult literacy, average years of schooling, average calorie intake, and per capita GNP.

The evolution of global commodity markets between 1985 and 1992 and the fall of the world price of coffee (Rwanda’s main export), «the arrival of the AIDS virus in the early 1980s, drought in 1984, excessive rain in 1987 and plant disease in 1988 all weighed in to contribute to declining production and food security levels. By 1989, an estimated 1 in 6 Rwandans was affected by famine (source: Pottier, 1993), 1/4 of all children was severely malnourished (World Bank, 1991), and some 50% of all children suffered from stunting (source: Uvin, 1998)» (Andy Storey, Structural violence and the struggle for state power in Rwanda, see Bibliography).

The worsening of the economic crisis and the growing mass impoverishment between the late 80s and the beginning of the 90s were accompanied by rising internal protests and growing political pressure from international aid donors and organizations. It was a potentially explosive situation for two reasons. Firstly, it questioned the absolute power of the ruling elite. Secondly, as Peter Uvin pointed out, indirect structural violence not only lowers the barriers against the use of direct violence but also «promotes explosions of acute, physical violence». Many scholars highlighted how structural violence contributes to interpersonal violence or creates conditions where interpersonal violence can happen.

How did the ruling elites respond to this socially inflammable situation and to the many risks of losing their absolute power?

We know it: they did it by using the good, old diversion political strategy.

Do you remember the pamphlet by Ngeze, entitled Appel à la conscience des Bahutu (A call to the consciousness of the Hutus) published in issue no. 6 of Kangura, dated December 1990? And what about a long article entitled Tout la vérité sur la guerre d’octobre 1990 au Rwanda [The whole truth about the October 1990 war on Rwanda] published in issue no. 114 of Nsango Ya Bisu, July 1991, and signed by Léon Mugesera? We analyzed both texts in the chapter Construction, Criminalization, Dehumanization of the Tutsis (in Rwandan Basketry 4).

In these relevant pieces of the hardliners’ campaign, the invasion of the RPF and the resulting war were brought into a historical horizon whose origins were deeply rooted in the past monarchical-feudal regime, «based on terror and on the serfdom exercised by the Tutsi minority over the Hutu majority» (Mugesera, cit.). This horizon had its cornerstones in the Bahutu Manifesto, the political program of PARMEHUTU and APROSOMA, the Social Revolution, and the Referendum of 1961 (all explicitly mentioned). In both texts, Belgian colonialism comes out of history without leaving any trace as if Belgians strolled through the country just a couple of times, and by accident. The bad guys are the Tutsi minority, and the good guys are the Hutu majority. The recent history of Rwanda from independence onwards, summed up in the triumphalist expression “30 ans de démocratie et justice sociale”, is jeopardized by the Tutsi abominable project which has its last step in the recent war on Rwanda: conquering the country, restoring their feudal-monarchical regime in a few days, and the ancient serfdom with it, exterminating all Hutus who are not ready to be enslaved.

Omar McDoom notes: «The history of Rwanda continued to be taught in terms of the Tutsi suppression of Hutu under Habyarimana’s regime (1973-1994)», as it was under the First Republic (Omar Shahabudin McDoom, Rwanda’s Ordinary Killers, 2005; see Bibliography). This ideological interpretation of the colonial past, which magically makes any responsibility of the Belgians disappear from history, is an excellent example of the diversion strategy, designed to racialize the condition of social oppression, poverty, and exclusion suffered by most Rwandans by bringing it within the Hutus vs. Tutsis scheme.

Many tiles of the ideological mosaic built by hardliners with extreme accuracy from 1990 to 1994 share the same goals with minor variations: they all racialized social tensions and exacerbated fears. It was a cynical policy entailing the radicalization of the oldest strategy used by the different ruling elites of Rwanda to maintain their grip on political and economic power.

In the 1920s, powerful bishop Classe and Belgian colonial authorities planned and implemented a complex policy of tutsification of the administration and racialization of the traditional Rwandan identities. This was a profitable strategy, able to channel social resentment and political claims into the racial horizon, getting rid of their dangerous nature of threats to the colonial power. This was the perfect diversion strategy.

Belgians knew that Rwanda could become a rentable colony only if the vast majority of people were subject to exploitation, which entailed forced labor, forced crops, humiliation, harsh physical punishments, fear, hunger, and famine: a dangerous, explosive mix. The Tutsi caste was chosen to make up «a barrier to anarchy and communism» not so much for their traditional ruling role over the mass but rather for their new identity, an identity that could give a strong ‘racial’ connotation to every kind of social resentment and anger, with a redirection effect that almost bypassed the Belgian political power and the Church.

After 1962 independence, on multiple occasions, the Hutu government not only permitted but also encouraged vengeance killings against Tutsi civilians to get remarkable political benefits: the violence against all Tutsis became part of the jingoistic rhetoric of the Kayibanda single-party regime, the main ingredient of its patriotic recipe, and one of its most effective political tools.

The Habyarimana’s regime not only continued the old use of racial identity cards but implemented apartheid measures and practiced a policy of racial discrimination by setting up a system of quotas that in theory was supposed to assure an equitable distribution of opportunities but in reality, was used to restrict the access of Tutsi to employment and higher education and increasingly discriminate against Hutu from regions other than the north (= that of Habyarimana’s family and associates).

The racial ‘card’ – from mild forms of racial segregation to mass killings of civilians – was the most effective ‘dirty weapon’ used by the Hutu oligarchy since Kayibanda times: before the Genocide, Rwanda knew no history of union struggles, labor strikes, and organized social protests. Rwanda’s trade union history up to 1994 can be told in a few lines. CESTRAR trade (Rwanda Workers’ Trade Union Confederation) is the oldest and most representative Rwandan trade union. It was founded in 1985, but it acquired its legal existence only in 1992, alongside the birth of multi-party politics, «in a situation where workers had not yet learnt the value of free and independent trade unions; the 1994 Genocide of Tutsi highlighted the precarious state of trade unionism through the loss of numerous trade union leaders and supporters, the destruction and plunder of trade union properties» (CESTRAR website). End of the story. It’s far too little, don’t you think?

Habyarimana’s ‘thieving elite club’ decided to play the ‘racial wild card’ when their firm grip on political and economic power started to wear down: the good, old, well-worked diversion strategy, elaborated by Monsignor Classe and enthusiastically approved by Belgians, seemed the right tool at the right moment, and after some dust off and spruce up, the Tutsi race was officially declared the mother of all Rwandan problems (I talked about this issue more in detail in the chapter On late 1990 to mid-1993 Genocide in Rwandan Basketry 6).

Look at the following ironic caricature, published in issue no. 16, January 1992, of the politically moderate magazine Rwanda Rushya. It depicts Hassan Ngeze, the editor-in-chief of Kangura, lying on a psychiatrist’s couch.

– I’m sick, doctor.

– What’s your illness?

– The Tutsi, Tutsi, Tutsiiiiiii…

Rwanda Rushya, issue no. 16, January 1992

The moderates of Rwanda Rushya, however, were tragically wrong: it wasn’t all paranoia. It was genocide.

Therefore, what I’ve already written about gender-based violence also applies to a more general level. In Rwanda, structural violence and social anger funneled into the racial violence – pressed by the ruling elite’s political approach that racialized fear, troubles, social tensions, and political clashes – and acted on the genocidal massacres just like an ignitable liquid spread on an arson: it accelerated its development, intensified its escalation, and enhanced its destructiveness.

And that’s not all: there’s more to fully understand the dramatic speed, intensity, and brutality of the genocidal fire: the complete absence of flame retardants.

Hope anthem by Gaël Faye ft Jali (Twibuke twiyubaka) is a poetry song or a poem sung to remember and honor the victims of the 1994 final phase. Gaël Faye is a French-Rwandan writer and singer, born in Bujumbura, Burundi, in 1982, of a French father and Rwandan mother of Tutsi origin. He lives in Kigali since 2015. He’s accompanied by Jali, a Belgian singer of Rwandan origin. The poem is in French and is worth any effort.

THE TACIT CONSENT OF THE CHURCHES

I’m not going to consider the heterogeneous behavior of Rwandan priests and nuns, some of which were killed during the final phase, some others protected and saved who sought refuge with them, and others were génocidaires and perpetrators, later judged and convicted as such. I’m about to consider the Churches as institutions speaking with one voice or, as in the case of the Catholic Church, with a prevailing voice.

The Catholic Church has always been Rwanda’s most important cultural institution, a prominent economic force, the most influential moral authority, and “a visible actor on the political scene” with a remarkable influence on the population (the definition is by Saskia Van Hoyweghen, author of The Disintegration of the Catholic Church of Rwanda: A Study of the Fragmentation of Political and Religious Authority, in African Affairs, Vol. 95, No. 380, July 1996). Since independence, the local Catholic hierarchy has been politically supporting the corrupt dictatorships of Kaybanda first and Habyarimana then. «For years the <Catholic> Church in Rwanda had tolerated a racist society, and in some churches, the so-called differences between the Hutu and the Tutsi people were preached from the pulpit» (Linda Melvern, Conspiracy to Murder, cit.). The powerful Hutu Archbishop of Kigali, Vincent Nsengiyumva, in charge since 1976, was a personal friend of President Habyarimana and the spiritual adviser to his wife, Madame Agathe.

In the 1990s, «Rwanda’s bishops continued to offer broad support for the government in the name of national security. After the initial RPF invasion of October 1990, Vincent Nsengiyumva reminded Catholics that love of country was a “duty incumbent on each of us” and praised Rwanda’s social progress under the Second Republic. (…). The bishops failed to name or condemn the Tutsi massacres unfolding across Rwanda between late 1990 and 1993. When killings were mentioned, blame was apportioned equally to “Tutsi” and “Hutu”» (J.J. Carney, Rwanda Before the Genocide, cit.).

Catholic Churches of Rwanda. Clockwise, top to bottom: Sanctuary of Our Lady of Kibeho, Parish Church of Rwamagana, Sainte Famille Church of Kigali, Cathedral of Butare.

What position did the Catholic Church take in April 1994, after Habyarimana’s assassination?

«The much-needed legitimacy that the interim government lacked was provided by the Catholic bishops of Rwanda on Monday, 11 April, when they issued a statement supporting the interim government and praising the Rwandan army who were “taking to heart the country’s security”. The bishops appealed to the people of Rwanda to support the interim government (…). The bishops expressed their shock at the killing of “political leaders and the innocent”. They condemned the authors of this killing whom they believed were prompted by “sadness and pity” at the death of the president» (Linda Melvern, Conspiracy to Murder, cit.). «They asked all Rwandans to “respond favorably to calls” from the new authorities and to help them realize the goals they had set, including the return of peace and security. (…) On April 17, the bishops spoke again, but only to call for an end to bloodshed for which they held both the RPF and the government responsible. » (Alison Des Forges, cit.).

«Even as Pope John Paul II denounced the massacres as “genocide” at the First African Synod on April 10, Rwanda’s bishops remained conspicuously silent. Vincent Nsengiyumva issued a vague statement on April 27 denouncing “grave troubles” that had cost the lives of “many innocent people” but did not link this to the interim government. Collectively, the bishops did not address the violence until May 13, and even here, the bishops attributed responsibility to both the RPF and the government, describing the massacres as “tragic events” rather than “genocide.” In the meantime, the bishops accompanied the interim government when it moved from Kigali to Gitarama (…). On June 20, Catholic bishops and Protestant leaders issued a joint statement blaming both sides for the violence and attributing “this dramatic situation” to the October 1990 war launched by the RPF with the assistance of Uganda. This document again failed to hold the interim government directly responsible for the genocide, arguing instead that “the [Habyarimana’s] assassination has been the occasion of a chain of ethnic reactions which have inspired massive massacres known by all in the country”» (J.J. Carney, Rwanda Before the Genocide, cit.).

«By not issuing a prompt, firm condemnation of the killing campaign, church authorities left the way clear for officials, politicians, and propagandists to assert that the slaughter actually met with God’s favor. Sindikubwabo finished a speech by assuring his listeners that God would help them in confronting the “enemy”. The RTLM presenter Valérie Bemeriki maintained that the Virgin Mary, said to appear from time to time at Kibeho church, had declared that “we will have the victory.” In the same vein, the announcer Habimana said of the Tutsi, “Even God himself has dropped them”» (Alison Des Forges, cit.).

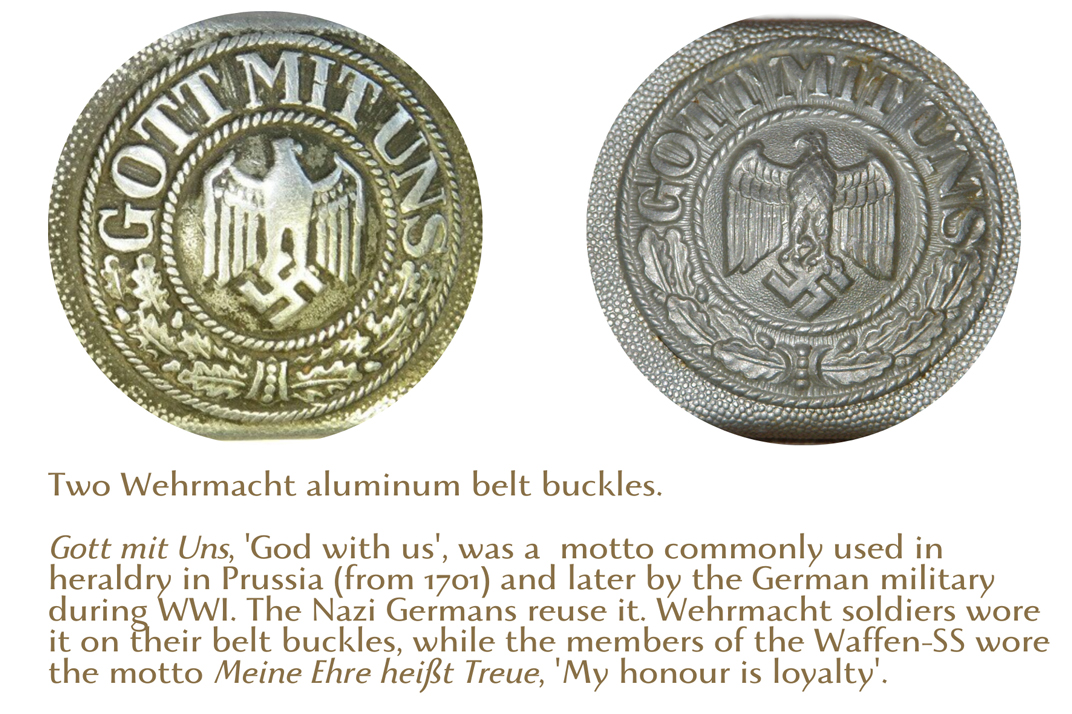

Gott mit uns. God is with us, on our side: bad memories.

The silence of the Catholic Church hierarchy during the first half of the final phase acted as a de facto tacit consent to genocide and pushed some members of the local clergy to collaborate directly or indirectly with authorities and perpetrators, in the belief that the Church’s silent agreement entailed a sort of moral approval. And what’s worse, this silence left a substantial mass of devout, observant people, the so-called “situated bystanders” or “disapproving witnesses”, without guidance, backing, advice, or even practical support to act against the massacres. That’s the reason why there was no critical mass opposing genocide.

The majority of political and intellectual opponents were killed in the days following the military coup; the leadership of the Social-Democratic Party was almost completely eliminated; the human rights community was decimated, together with many lawyers, journalists, and academics. The foreigners had all fled the country, and the international community turned its back on Rwanda. UNAMIR soldiers were a handful of men unable to defend themselves, flanked by a couple of brave international activists and observers. The Rwandan Catholic Church was the only potential levee to horror; it was the only authority that could have influenced a large sector of the population. The Catholic bishops could have acted as powerful retardants, able to slow down the spread of fire or reduce its intensity. Instead, they chose a complicit silence and later some vapid, inane formal words, and by choosing to maintain their politically blind conservativism, they abdicated all moral responsibility.

As to other Churches, well, their representatives did even worst. On May 12, 1994, Jonathan Ruhumuliza, the Anglican assistant bishop of Kigali, wrote a letter to José Chipenda, secretary general of the All Africa Council of Churches. Ruhumuliza defended the government and blamed the mass killings on the RPF: «After the setting up of a new government, we see that things are changing in a good way. The ministers are doing their best to bring back peace in the country although they are facing many problems (…). The fightings around are still on there and we worry about what is happening; because the rebels are destroying everything, killing everybody they meet while the Government is trying to bring peace to the country».

A few weeks later, Ruhumuliza and Augustin Nshamihigo, Anglican archbishop of Rwanda, «held a press conference in Nairobi <in Kenya> in which they attempted to explain events in Rwanda in a light highly sympathetic to the genocidal government, blaming the violence in the country on the RPF». (Timothy Longman, Christianity and Genocide in Rwanda, see Bibliography).

«Far from condemning the attempt to exterminate the Tutsi, Archbishop Augustin Nshamihigo and Bishop Jonathan Ruhumuliza acted as spokespersons for the genocidal government», Alison Des Forges commented.

On November 20, 2016, the Rwandan Catholic Church apologized for its role in the 1994 final phase: «We apologize for all the wrongs the Church committed. We apologize on behalf of all Christians for all forms of wrongs we committed. We regret that church members violated (their) oath of allegiance to God’s commandments. Forgive us for the crime of hate in the country to the extent of also hating our colleagues because of their ethnicity. We didn’t show that we are one family but instead killed each other». This statement, signed by the nine bishops of the Catholic Episcopal Conference of Rwanda, was read out in parishes across the country. The Bishop of Butare Philippe Rukamba, spokesperson for the Catholic Church of Rwanda, said that the statement was timed to coincide with the formal end Sunday of the Holy Year of Mercy declared by Pope Francis to encourage greater reconciliation and forgiveness.

On March 20, 2017, Pope Francis asked Rwandan President Paul Kagame for forgiveness for the “sins and failings” of the Catholic Church during the 1994 final phase. A public announcement from the Holy See Press Office said that Pope Francis «conveyed his profound sadness and that of the Holy See and of the Church for the genocide against the Tutsis. He expressed his solidarity with the victims and with those who continue to suffer the consequences of those tragic events and, evoking the gesture of Pope St John Paul II during the Great Jubilee of the Year 2000, he implored anew God’s forgiveness for the sins and failings of the Church and its members, among whom priests, and religious men and women who succumbed to hatred and violence, betraying their own evangelical mission. (…). In light of the recent Holy Year of Mercy and of the Statement published by the Rwandan Bishops at its conclusion, the Pope also expressed the desire that this humble recognition of the failings of that period, which, unfortunately, disfigured the face of the Church, may contribute to a ‘purification of memory’ and may promote, in hope and renewed trust, a future of peace, witnessing to the concrete possibility of living and working together, once the dignity of the human person and the common good are put at the center».

President Kagame meets with His Holiness Pope Francis, Vatican City, March 20, 2017.

Photo licensed under Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 2.0 Generic (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0).

In 2020, «the Church of England has reinstated a Rwandan bishop who left his role as a parish priest in Worcestershire after he was accused of complicity in the 1994 genocide of hundreds of thousands of Tutsis» (Chris McGreal and Harriet Sherwood, Church welcomes back Rwandan bishop accused of defending genocide, Sun 31 May 2020, The Guardian). The Rwandan bishop is Jonathan Ruhumuliza, now 64.

THE RESPONSIBILITIES OF THE INTERNATIONAL COMMUNITY

Another powerful flame retardant that could have contained or even extinguished the Rwandan fire is made up by the international community that, for multiple reasons and much political opportunism, made a series of short-sighted, politically mediocre, and morally wicked choices.

For international community I mean the UN Security Council and its Secretary-General from 1992 to 1996, Egyptian politician and diplomat Boutros Boutros-Ghali; the UN Department of Peace-keeping Operations (DPKO) managed by a ‘triumvirate’ made up by the retired General Maurice Baril, Kofi Annan, and Iqbal Riza; France and its President François Mitterrand; the United States and Bill Clinton’s administration, especially Madeleine Albright who was U.S. ambassador to the United Nations from 1993 to 1997; Belgium and his government at the time, especially its prime minister Jean-Luc Dehaene, in charge from 1992 until 1999; Great Britain under the leadership of conservative John Major; the English ambassador and permanent representative to the United Nations was David Hannay, Baron Hannay of Chiswick, who together with Madeleine Albright persuaded the Security Council to avoid the term of ‘genocide’ when describing what was happening in Rwanda in order to escape any due intervention, according to the International Law; the Organisation of African Unity (OAU) and his secretary general, Tanzanian Salim Ahmed Salim.

«The major actors in the drama, the world that mattered to Rwanda – most of its Great Lakes Region neighbors, the UN, and the major western powers – knew a great deal about what was happening. (…). There can be not an iota of doubt that the international community knew that something terrible was underway in Rwanda, (…). <but> the world nevertheless stood by and did nothing» (The Preventable Genocide, 7.10, cit.).

As Mahmood Mamdani wrote, the Jenoside yakorewe abatutsi was organized and implemented before the eyes of the entire international community.

«Policymakers in France, Belgium, the United States, and at the United Nations all knew of the preparations for massive slaughter and failed to take the steps needed to prevent it. Aware from the start that Tutsi were being targeted for elimination, the leading foreign actors refused to acknowledge the genocide. To have stopped the leaders and the zealots would have required military force; in the early stages, a relatively small force. Not only did international leaders reject this course, but they also declined for weeks to use their political and moral authority to challenge the legitimacy of the genocidal government. They refused to declare that a government guilty of exterminating its citizens would never receive international assistance» (Alison Des Forges, cit.).

«The evidence is clear that there are a small number of major actors whose intervention could directly have prevented, halted, or reduced the slaughter. They include France in Rwanda itself; the US at the Security Council, loyally supported by Britain; and Belgium, which fled from Rwanda and then tried to leave UNAMIR dismantled altogether after the genocide had begun. Nigeria’s Permanent Representative to the UN, Ambassador Ibrahim Gambari, has reminded us that “There is nothing wrong with the United Nations that is not attributable to its members,” which led him to conclude: “Without a doubt, it was the Security Council, especially its most powerful members, and the international community as a whole, that failed the people of Rwanda in their gravest hour of need”. In the bitter words of General Dallaire, echoed by his second-in-command, Colonel Marchal, “the international community has blood on its bands”» (The Preventable Genocide, 15.40, cit.).

The behavior of all actors of the international community is a very complex issue I do not want to deal with here for a simple reason: it’s one of the most discussed and treated topics related to the 1990-94 Rwandan Genocide. You can find many articles, documents, online reports, and essays about the fallacies of the US, France, UK, Belgium, and the failure of the United Nations in the final Bibliography.

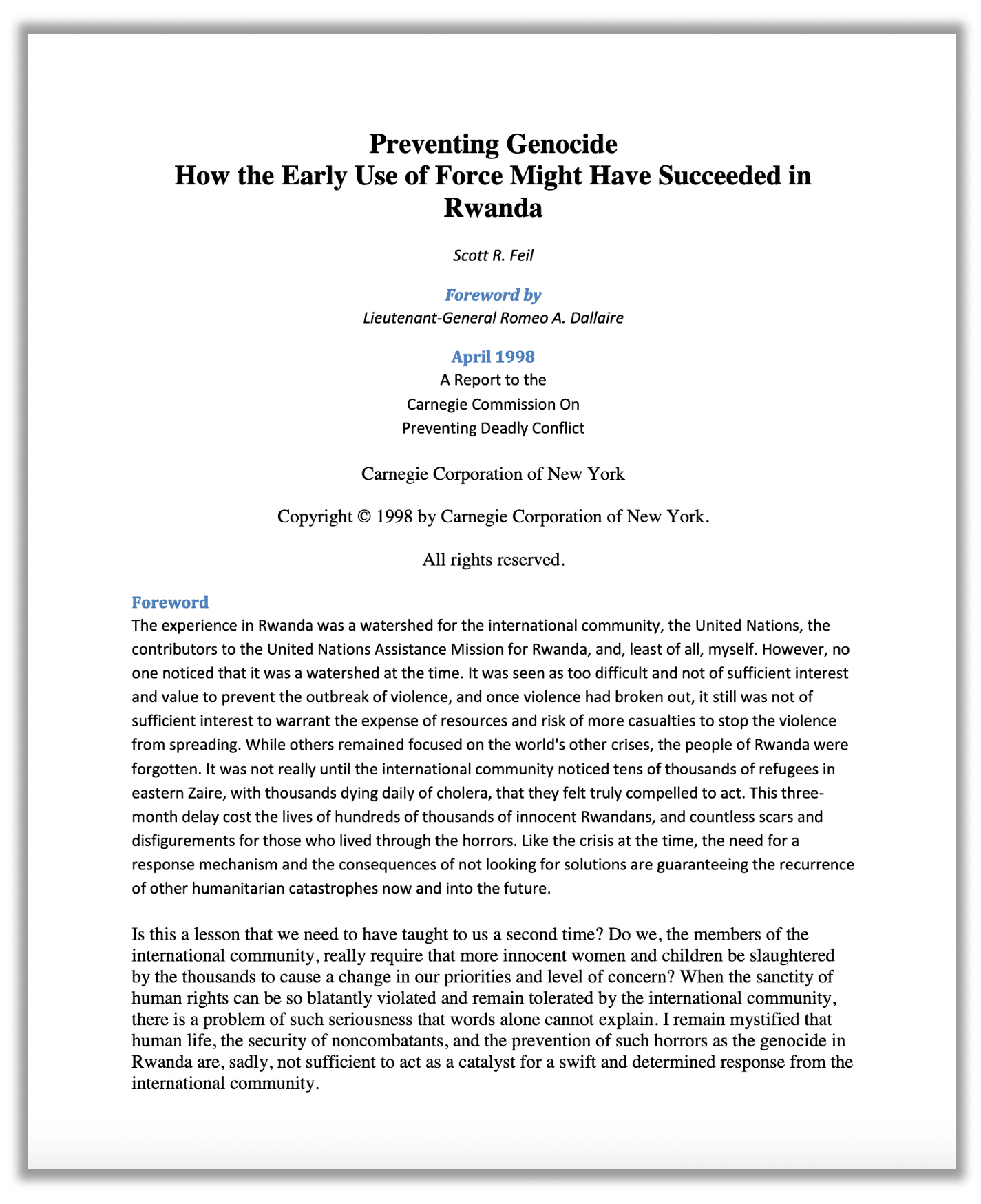

I’m about to consider only a relevant report signed by Scott R. Feil, entitled Preventing Genocide: How the Use of Force Might Have Succeeded in Rwanda. Here it is.

Scott R. Feil, Preventing Genocide: How the Early Use of Force Might Have Succeeded in Rwanda, Carnegie Corporation of New York, 1998, with a Foreword by Roméo Dallaire.

This text is the result of a project by the Carnegie Commission on Preventing Deadly Conflict, the Institute for the Study of Diplomacy at Georgetown University, and the United States Army, which aimed to consider whether the introduction of international military force into the situation in Rwanda in 1994 could have had any effect on the situation there and what the nature of such an intervention might have been. The report can be downloaded here or more directly here.

The results of the report are based on a series of data collected by an international panel of distinguished senior military leaders and their serious analysis. The author concludes «that a modern force of 5,000 troops, drawn primarily from one country and sent to Rwanda sometime between April 7 and 21, 1994, could have significantly altered the outcome of the conflict. Although the organized combatant factions in Rwanda were fairly capable light infantry and such an operation would have entailed significant risk, the introduction of a combat force large enough to seize, at one time, key objectives all over the country would have, in the words of one senior officer, “thrown a wet blanket over an emerging fire”. More specifically, forces appropriately trained, equipped, commanded, and introduced in a timely manner, could have stemmed the violence in and around the capital, prevented its spread to the countryside, and created conditions conducive to the cessation of the civil war between the RPF and the government forces» (Scott R. Feil, Preventing Genocide: How the Early Use of Force Might Have Succeeded in Rwanda, cit.).

Moreover, as Alison Des Forges highlighted, «international leaders had available means other than armed force to influence the interim government but did not use them. They could have eliminated the hate radio, an action which would have had great symbolic as well as a practical effect, but they did not do so. Nor did major donors ever threaten publicly that all financial assistance in the future would be withheld from a government guilty of genocide. Such a warning would have raised immediate concern among the many Rwandans who knew how much local and national authorities depended on foreign support and might have caused them to reject the interim government» (Alison Des Forges). When the international community and the United Nations took a decision, it was too late.

So, the Jenoside yakorewe abatutsi could have been prevented and even stopped. As Roméo Dallaire wrote, «it was seen as too difficult and not of sufficient interest and value to prevent the outbreak of violence, and once the violence had broken out, it still was not of sufficient interest to warrant the expense of resources and risk of more casualties to stop the violence from spreading. (…). Is this a lesson that we need to have taught to us a second time? Do we, the members of the international community, really require that more innocent women and children be slaughtered by the thousands to cause a change in our priorities and level of concern? When the sanctity of human rights can be so blatantly violated and remain tolerated by the international community, there is a problem of such seriousness that words alone cannot explain» (Ibidem).

Roméo Dallaire speaking at the St. Joseph’s Health Care Foundation, London Ontario, in September 2017.

Photo by Michelle Campbell, under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license.

«Rwanda will never ever leave me. It’s in the pores of my body. My soul is in those hills, my spirit is with the spirits of all those people who were slaughtered and killed that I know of, and many that I didn’t know».

THE LAST QUESTION: HOW TO EXPLAIN THE LARGE-SCALE CIVILIAN INVOLVEMENT IN THE GENOCIDE?

- The so-called ‘hate media’ are not at all media of ‘hate’

Many scholars recognize that Rwandan media played an exceptionally crucial role in the genocide. The texts and speeches I’ve talked about in the previous chapters are part of the so-called ‘hate media’, in French ‘les médias de la haine’. This is an umbrella expression to designate those media (texts, speeches, radio broadcasts) that, between 1990 and 1994, spread the ideology of genocide, the ‘media of the Genocide’ in short. Like all identification tags, this label is quite useful – when you talk about the ‘hate media’ everybody knows what you’re talking about – but is a perfunctory marker, and a source of deep misunderstandings.

Calling these texts ‘hate speeches’ is quite misleading because they were not aimed at spreading and exacerbating intolerance, hate, or disdain against Tutsis. And you know why? Because some degree of intolerance and disdain against Tutsis was already common in Rwanda’s society. It was an integral part of the late 50s Social Revolution, the ‘Hutu Nation’ concept (which was the groundwork of the 1993 Hutu ‘Pawa’), the First Republic, the Kaybanda’s regime, the 1963 mass killings, and all of the followings, the Second Republic, the Habyarimana’s regime and its racial discrimination policy. The writer Yves Simon wrote it clearly without cutting the hem off truth’s garment: «A genocidal ideology had undermined, divided, and administered Rwanda since 1959. For more than thirty years, Tutsis were insulted, called cockroaches, parasites, and traitors» (Mémoire d’un génocide, cit.). Kennedy Ndahiro, the editor of the Rwandan daily newspaper “The New Times”, wrote: «Yet the dehumanization had started long before the Radio Télévision Libre de Mille Collines urged its listeners to “exterminate the cockroaches.” The killings in 1994 were a culmination of decades of hate-mongering, the indoctrination that began even before independence. In 1959, Joseph Habyarimana Gitera, a leader of the radical Hutu political party APROSOMA, openly called for the elimination of the Tutsi “vermin.” The stigmatization and dehumanization of the Tutsi had begun. When the first of the many anti-Tutsi pogroms broke out that year, Gitera was overjoyed» (In Rwanda, We Know All About Dehumanizing Language, in The Atlantic, April 13, 2019).

Many walls raised during the First and the Second Republic have been mixed with more hate than mud.

Therefore, it can be assumed that the main purpose of the ‘hate media’ was to light the fire of racial hatred only by ignoring 30 years of Rwandan history.

Fear, disdain, and hatred against the Tutsis were not ‘inventions’ of the early 1990s state and private media, just like German anti-Semitism was not an ‘invention’ of Hitler and Goebbels. (In Germany, anti-Semitism enjoyed more than 150 years to deeply soak in the nationally widespread weltanschauung). The ‘hate speeches’ did not have to fan the flames of violence: Rwanda was already at war, and the fire was already spreading. Actually, the strategy behind all of these badly called ‘hate’ articles, public speeches, and radio broadcasts was much more complex and refined.

In all these texts, including those I have considered, there was a common denominator: a call to action.