NAVAJO CHURRO SHEEP AND WOOL 2

USA on the globe.

Licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported.

SOUTHWESTERN STATES

THE SURPRISING HISTORY OF THE NAVAJO PEOPLE AND THEIR SHEEP

UNDER U.S. RULE

As we have seen, Mexico gained its independence from Spain in 1821.

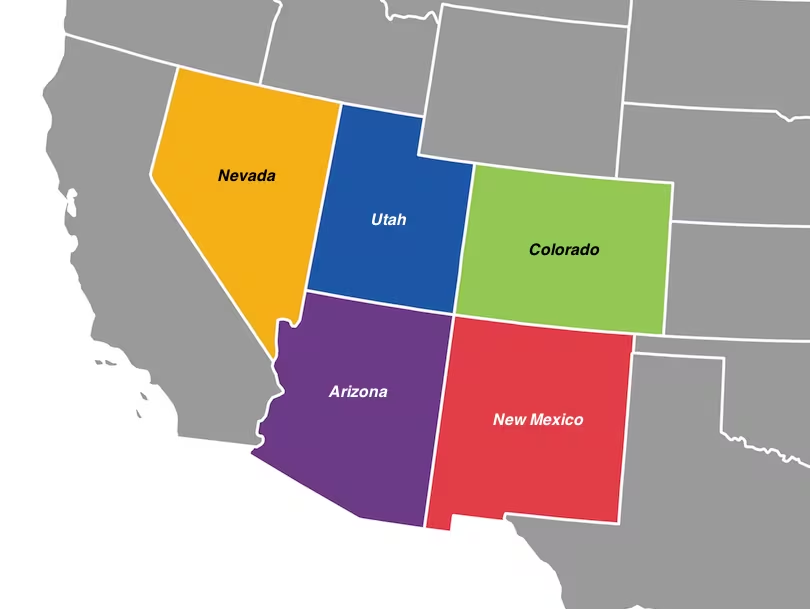

The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo (February 2, 1848) officially ended the Mexican-American War (1846-1848). Mexico ceded about 525,000 square miles of territory to the United States, including California, Nevada, Utah, most of Arizona, and parts of New Mexico, Colorado, and Wyoming. The U.S. paid Mexico $15 million for this land. Texas had already been annexed by the U.S. in 1845, leading to the war, but the treaty confirmed the U.S. claim to Texas and established the Rio Grande as its border. Small portions of present-day Kansas, Oklahoma, Nebraska, and Wyoming were included in the Mexican Cession. However, most of these territories were acquired through later adjustments, including the Compromise of 1850 and the Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854.

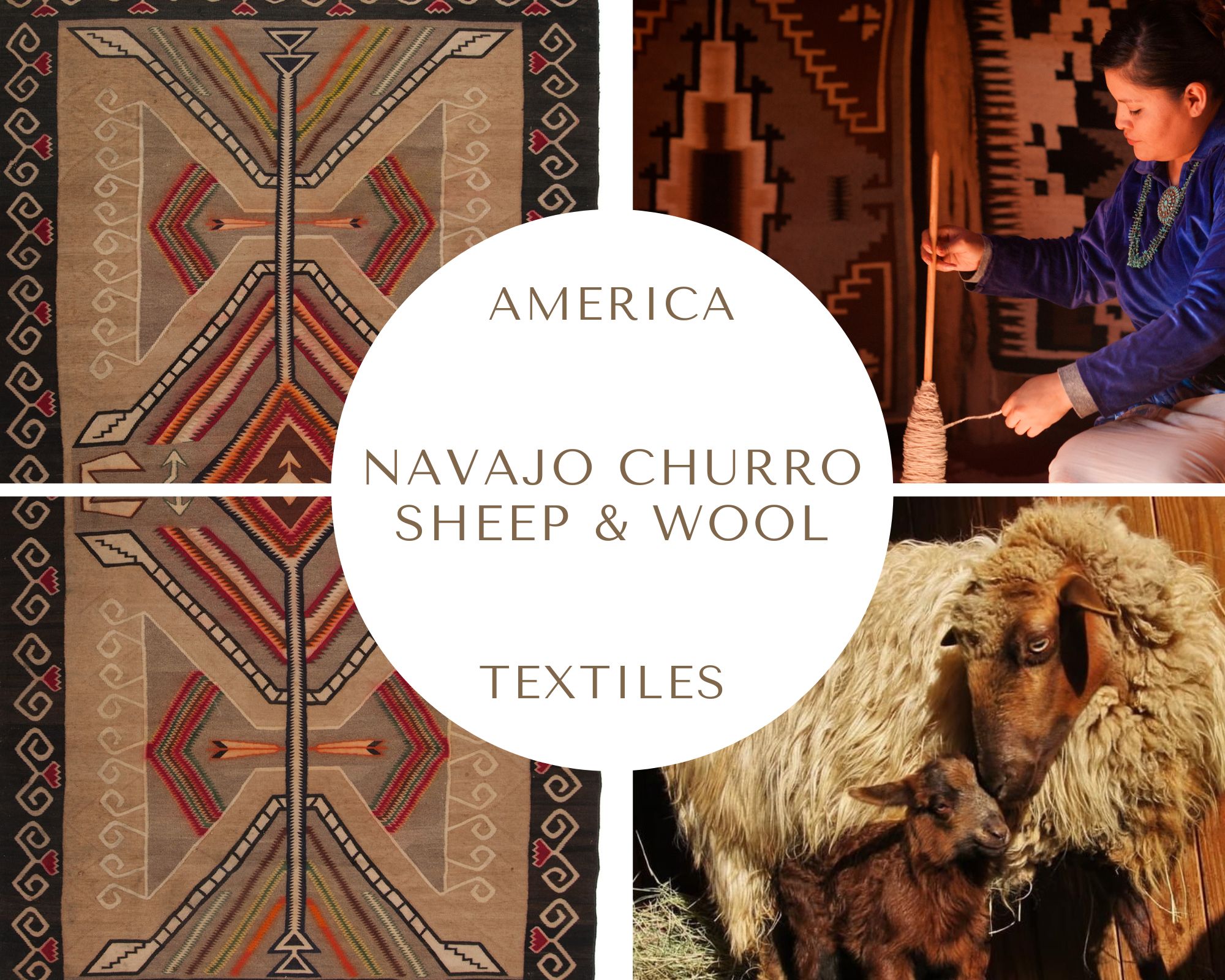

By the mid-19th century, the Navajo (Diné) were among the wealthiest indigenous groups in the Southwest, largely due to their trading economy, extensive livestock (horses, mules, donkeys, cattle, and hundreds of thousands of sheep and goats), and agricultural productivity (they had an abundance of corn, wheat, beans, squash, melons, and peaches). They were known for their highly valued hand-woven wool textiles (blankets and rugs), which they traded with other Native groups and settlers. In short, the Diné people were a major player on the Southwestern stage.

«As the Diné would soon discover, the Americans represented a different kind of presence and determination» (P. Iverson, cit.). To the Americans, all Native people, including the Navajos, represented an obstacle to "progress," a bright and positive word that concealed such a predatory attitude toward land and resources that it did not shrink from the possibility of resorting to radical forms of "ethnic cleansing".

«“You are in the way.” That is, in the end, what the Americans said» to Navajos. «“You will lose your lands,” the Americans said. “If you resist, you will lose your lives.”». (P. Iverson, ibidem).

Tensions between Navajos and white settlers began almost immediately and escalated in the early 1860s. In 1863, Major General James H. Carleton ordered Colonel Kit Carson to conduct a scorched-earth campaign against the Navajos. Carson's campaign was brutal: his troops destroyed crops, burned hogans, cut down fruit trees, slaughtered livestock, and destroyed water sources in an effort to devastate the Navajo economy and drive the population to starvation and despair.

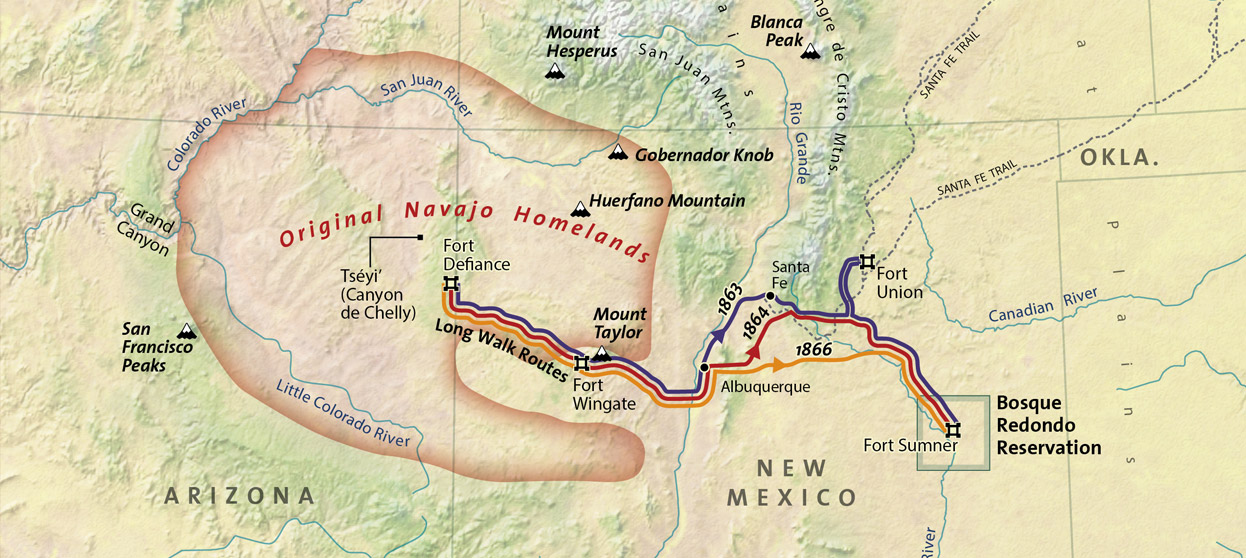

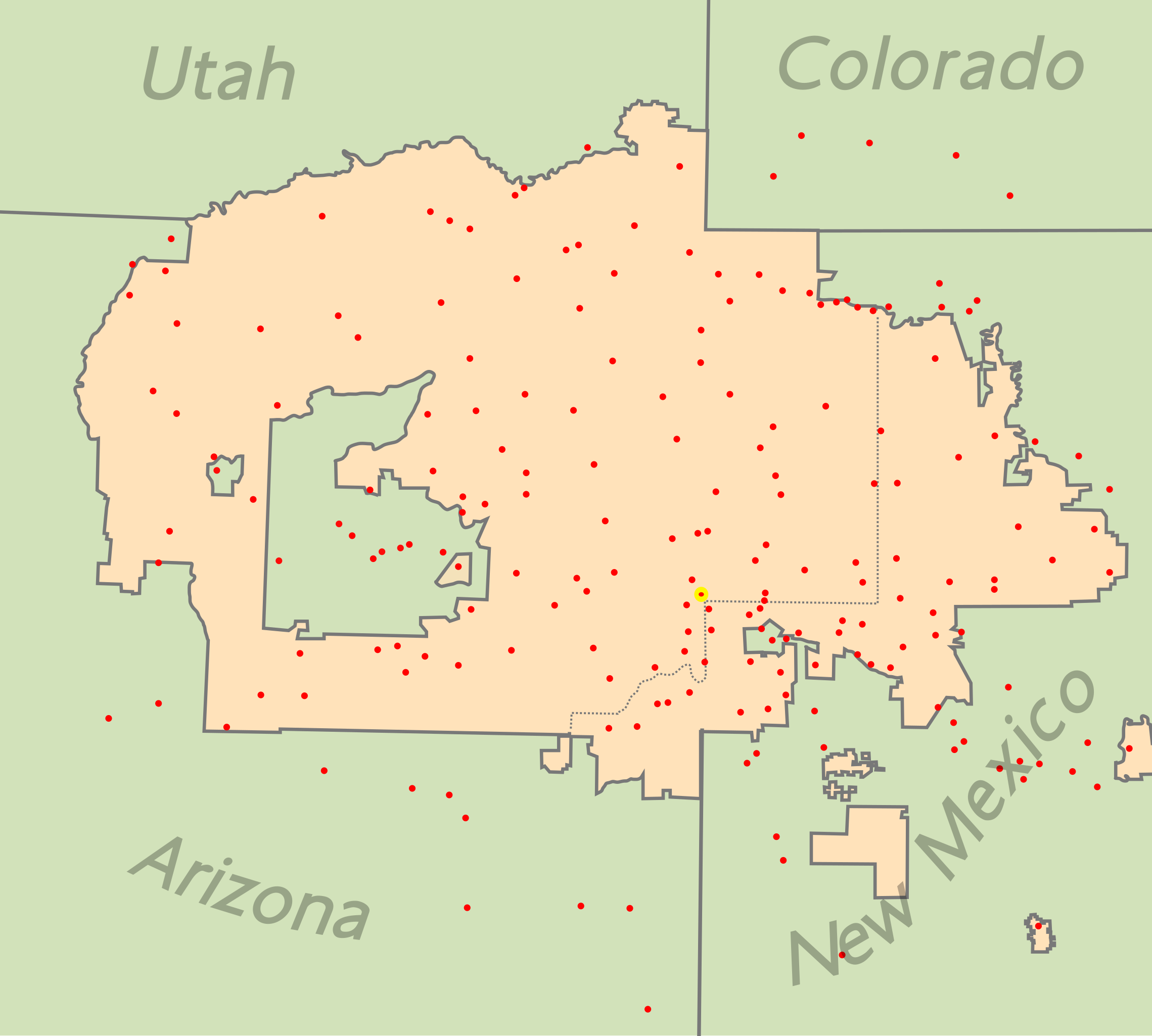

By the end of 1863, thousands of starving Navajo survivors surrendered at Forts Defiance and Wingate. The U.S. military then forced them to march between 250 and 450 miles to the Bosque Redondo Reservation near Fort Sumner, New Mexico. «The Long Walk was not a single event. Neal Ackerley has documented fifty-three separate episodes of the Long Walk, dating from August 1863 to the end of 1866.» (P. Iverson, cit.). During this forced relocation, the Navajo people were ordered to march without food or water and under the watch of soldiers who shot on the spot elders, children, the disabled, pregnant women, and women in labor who couldn't keep up. (This horror has been extensively documented). The great differences in the distances covered on foot depended on the different routes taken, as the map below clearly shows.

Between 1863 and 1866, more than 10,000 Navajo (Diné) were forcibly removed to the Bosque Redondo Reservation at Fort Sumner in present-day New Mexico. During the Long Walk, the U.S. military marched Navajo (Diné) men, women and children between 250 and 450 miles, depending on the route. In kilometers, this distance is approximately 402 to 724 kilometers.Text and map from Native Knowledge 360°, National Museum of the American Indian (NMAI), Smithsonian Institution, USA.

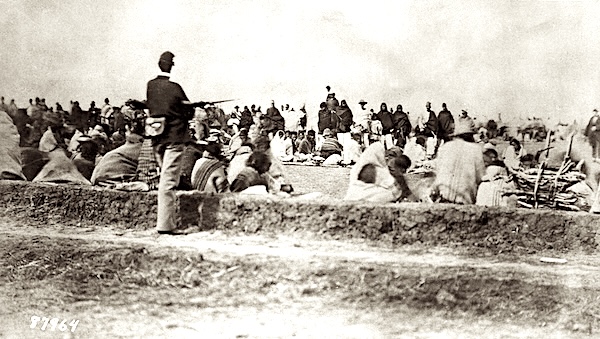

A man in military uniform stands near Navajo men and women at Fort Sumner, New Mexico, after their forced removal from their homelands (the "Long Walk"). They were then moved to the Bosque Redondo Reservation. Date: 1864-1865. Source: Denver Public Library Special Collections [call number X-33101], CO, USA.

The Bosque Redondo, called Hweeldi by the Diné, served as an internment camp where 8,570 Navajos were imprisoned from 1864 to 1868. Conditions were brutal:

- Navajos lived in pits dug into the ground; the camp was was overcrowded and poorly supplied;

- Navajos endured freezing winters and scorching summers without adequate protection;

- Starvation and disease (especially dysentery and smallpox) were widespread;

- Crops failed due to drought and pests;

- Sexual violence against Navajo women and girls was also a documented problem;

- During their internment, the Diné were prevented from practicing ceremonies, singing songs, or praying in their own language.

Thousands of Navajos died during the internment. Some estimates range from 2,000 to 3,000 due to poor record keeping. All of them were buried in unmarked graves.

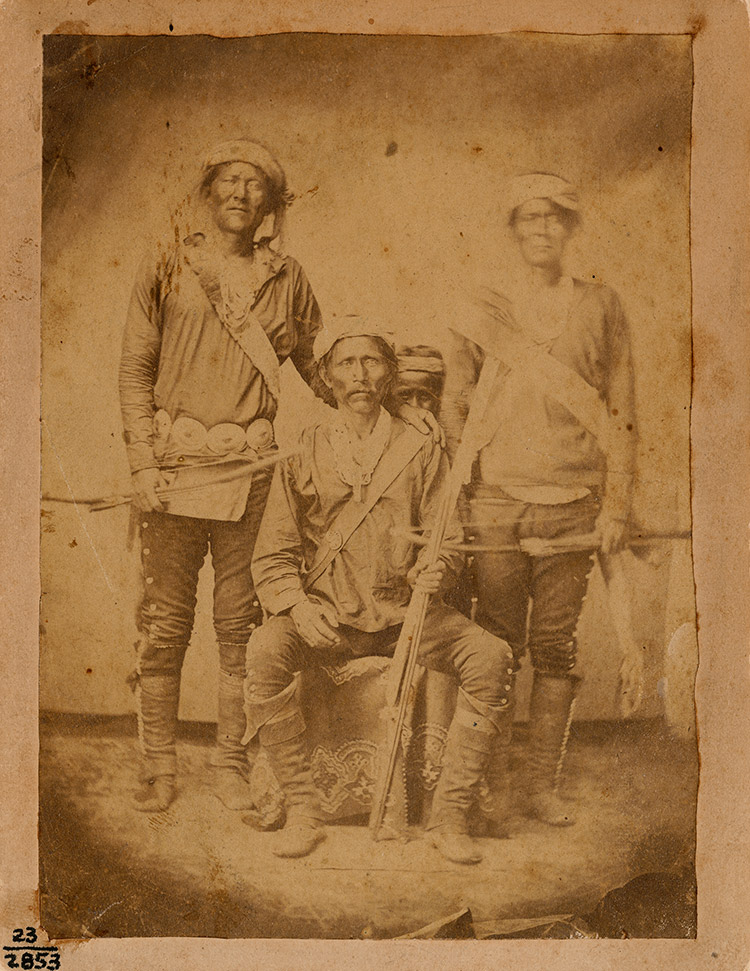

Navajo chiefs accused of counterfeiting ration tickets at Bosque Redondo, Fort Sumner, New Mexico, 1866. Photo by the United States Army Signal Corps. Source: New Mexico's Digital Collections, USA.

From the beginning, the plan was to force the Navajo (Diné) to adopt white American cultural values; however, most Navajos resisted cultural assimilation and forced Christianization. The reservation project ultimately failed, costing the U.S. government approximately ten million dollars while failing to achieve its goal of assimilating the Navajo.

On May 28, 1868, Lieutenant General William Sherman and Samuel Tappan negotiated a treaty with Barboncito and Manuelito, Navajo leaders chosen to represent their people. «Despite their horrific treatment at the hands of the United States, the Navajo (Diné) leaders successfully used the treaty process to secure a return to their homeland and to forge a diplomatic relationship with the United States government.» (NK 360°)

Studio portrait of Navajo leaders Barboncito (seated, holding rifle), Manuelito (at left, holding bow and arrow), and Calletano, Manuelito's brother (at right, holding bow and arrows), 1868. Photograph by Valentin Wolfenstein, National Museum of the American Indian, P20815. Source: NK360°.

The 1868 treaty allowed the Navajo to return to part of their homeland, one of the few instances in which a Native American group was allowed to return to its land after being forcibly removed. June 1, 1868 is still celebrated today as Treaty Day.

On June 18, 1868, 7,000 Navajo formed a column at least ten miles long as they began their journey home. The treaty ended their intense suffering and made them more amenable to trade with whites. By 1877, six trading posts had been established on Navajo land.

Upon returning home, the Navajo struggled to reestablish their pastoral way of life, revive their cultural practices, and redouble their efforts to save the Churra-Navajo breed from near extinction. Despite the hardships they endured, they maintained their cultural identity and gradually rebuilt their communities and herds in the late 19th century.

The Long Walk by C-Bar Studios

The Diné people «would never forget the tragic dimensions of this experience. They would always carry with them the trauma of the Carson Campaign and the Long Walk, the painful exile from Diné Bikéyah, and the many indignities and insults that they had had to endure. At the same time, they would recall that they had made their way through this crisis.» (P. Iverson, cit.)

Shí Naashá by Radmilla Cody featuring Mattee Jim and Stella Martin.

Shí naashá (I'm going) is a Navajo song, composed in 1868 to commemorate their return to homeland and the end of their deportation at Bosque Redondo. It's a song of happiness and joy: Shí naashá, shí naashá, shí naashá biké hózhǫ́ lá, "I am going, I am going, I am following the path; the way of beauty is around me". «This song, as well as many other Navajo songs, refers to “walking in beauty” or “Hózhǫ́,” which is a Diné core belief and way of life. The beauty associated with the word “hózhǫ́” in Navajo does not refer to physical appearance. Instead, it roughly translates as the concept of balance, peace, harmony and beauty. This is the end goal for each Diné person. To walk in beauty also means to develop spiritual, emotional, physical, and mental strength to get beyond fears and be able to have joy, happiness, confidence, and peace.» (Source: Brigham Young University and Navajo Nation Department of Diné Education).

The Bosque Redondo Memorial, located 6.5 miles (10.5 km) southeast of Fort Sumner, New Mexico.

«In 2005, the New Mexico State Monuments Division (now Historic Sites) and the Museum of New Mexico Foundation, with strong support from the Diné and Ndé, created the Bosque Redondo Memorial. It stands today to acknowledge the events of the 1860s and to allow those affected by the history to have a voice to tell their history. Designed by Navajo architect David Sloan in the shape of a hogan and a tepee, the museum and an interpretive trail provide an exhibit and educational programs to all who seek it.» (Source: New Mexico Historic Sites)

THE POWER OF WORDS 1

In contemporary military and government communications of the 1860s, the Long Walk was likely described in more administrative terms as a "forced removal," "relocation," or "deportation" of the Navajo to the Bosque Redondo Reservation. General James Carleton, who ordered the operation, framed it as part of his plan to "civilize" the Navajo, explaining that placing them on a reservation far "from the haunts and hills and hiding places of their country" would help them "acquire new habits, new ideas, new modes of life".

Nothing new under the sun.

As early as the late 1840s, Colonel John Macrae Washington, who had become the new military commander and provisional governor of New Mexico in 1848, informed the adjutant general in Washington in February 1849 of the need for the "savage tribes" to "change from their present habits of wandering to the pursuit of agriculture, from the state of savagery to that of civilization".

«In his employment of such language, Washington very much expressed the sentiments of the day», adds historian Peter Iverson. At that time, «Americans believed that most, if not all, Indians must be compelled upward out of “savagery” and “barbarism” into the higher stage of “civilization.”» (P. Iverson, cit.) If this “improvement” required coercion, then so be it.

Thus, the 1864 Act was conceived and described by Americans (often in good faith) as a resettlement and civilization project, a re-education program to turn "savages" into modern farmers, good Christians, and docile, easily controllable subjects. The Long Walk was the necessary price to be paid for this "improvement". «Ultimately the reservation envisioned by Carleton symbolized the two overarching impulses of “white” Americans toward different peoples “of color”: segregation and assimilation.» (P. Iverson, cit.). And 'cleansing', in case the first two options didn't produce the expected results (namely the liberation of Native land rich in natural resources and agricultural potential to be divided among new private owners).

But it is not the revolting paradox at the heart of this project of education and forced Christianization that I want to draw your attention to.

No.

I want to emphasize that the Long Walk was not a "walk". It was what we're now entitled to call a "death march" in its own right.

Death Marches: Definition, Legal Status, and Humanitarian Violations

Death marches are forced marches of prisoners of war or civilians under extreme conditions, often in mass deaths from starvation, exhaustion, abuse, and execution (Cohen, 2012). They constitute serious violations of international law and have been prosecuted as war crimes and crimes against humanity under various legal frameworks.

In academic and legal discourse, death marches are distinguished from ordinary forced marches by the intentional cruelty and deliberate conditions that lead to mass death (Bartrop, 2017). Typical characteristics include:

- Forced physical exertion under brutal conditions;

- Denial of food, water, and medical care;

- Beatings, torture, and humiliation;

- Summary execution of those unable to continue.

The Third Geneva Convention (1949) establishes protections for prisoners of war and requires humane treatment during evacuation. Relevant provisions include:

- Article 20: Mandates humane conditions during transfers;

- Article 13: Prohibits acts causing unnecessary suffering;

- Article 26: Requires adequate food and water.

The Fourth Geneva Convention, which protects civilians, contains similar provisions (Articles 27-34) against inhumane treatment during forced relocation (ICRC, 2020).

After World War II, death marches were prosecuted as war crimes and crimes against humanity at the Nuremberg Trials and the International Military Tribunal for the Far East (IMTFE).

- Nazi death marches (Auschwitz, Dachau, etc.) were judged as acts of extermination and murder (Trial of the Major War Criminals, 1947).

- The Bataan Death March (1942) and Sandakan Death March (1945) led to the conviction of Japanese officers for the intentional killing and mistreatment of prisoners of war (Piccigallo, 1979).

The Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court (ICC) classifies acts constituting death marches under:

- Article 7 (Crimes Against Humanity): Murder, extermination, forcible transfer, deportation, and inhumane acts

- Article 8 (War Crimes): Intentional killing, torture, and inhumane treatment (ICC, 1998).

Death marches violate fundamental human rights under the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR):

- Right to life (Article 6)

- Prohibition of torture and inhumane treatment (Article 7)

- Dignity of the deceased (Article 16, Fourth Geneva Convention) (ICRC, 2020).

The UN Special Rapporteur on Extrajudicial Executions has emphasized that victims of mass killings, , including those abandoned in death marches, must be treated with dignity in death (UNHRC, 2016).

Conclusion

Death marches are among the most serious violations of international humanitarian and human rights law. They have historically been prosecuted and remain a relevant legal issue in conflicts where forced evacuations result in mass deaths. Ensuring accountability for such crimes is essential to the maintenance of international justice.

Definitions that clarify when the transfer of military and civilian prisoners violates inalienable rights and constitutes a grave crime such as a "death march" are essential today because they serve to expose the ideological labels and bureaucratic terms behind which the worst crimes against humanity have been and continue to be hidden. So we can conclude that The Long Walk was not a crime against the Navajo: it was a crime against all of humanity. Including us.

The Navajo musician Clarence Clearwater walked hundreds of miles to Fort Sumner back in 1968, on the 100th anniversary of the treaty that ended the "Long Walk" era. Martin Link.

References

- Bartrop, P. (2017). The Holocaust and Other Genocides: An Introduction. ABC-CLIO.

- Cohen, P. (2012). History and Memory in Postwar Japan. Princeton University Press.

- ICRC (2020). Geneva Conventions and Additional Protocols. International Committee of the Red Cross.

- ICC (1998). Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court.

- Piccigallo, P. (1979). The Japanese on Trial: Allied War Crimes Operations in the East, 1945–1951. University of Texas Press.

- Trial of the Major War Criminals (1947). Nuremberg Trial Proceedings. Nuremberg Military Tribunal.

- UNHRC (2016). Report of the Special Rapporteur on Extrajudicial, Summary, or Arbitrary Executions. United Nations Human Rights

NAVAJOS FROM THE LATE 19th CENTURY TO THE LATE 20th

The history of the Navajo people from the late 19th century to the late 20th century is marked by significant events that shaped their cultural, economic, and political landscape. The Navajo people overcame significant challenges while making strides toward greater autonomy and cultural preservation. Here are just some of the major events during this period.

LATE 19th CENTURY

Reservation Era and Expansion

After the Treaty of Bosque Redondo in 1868, the Navajo were allowed to return to a portion of their ancestral lands. The reservation initially encompassed about 3.5 million acres / 14,100 square meters. Over time, through various expansions, it grew to more than 16 million acres by the mid-20th century. Today the Navajo Nation covers an approximate area of 17,544,500 acres / 71,000 square meters.

Economic and Cultural Challenges

After the Treaty, the Navajo faced economic challenges, including conflicts over livestock grazing, railroad development, and mining activities on their lands. These activities often occurred without adequate tribal consent, resulting in resource exploitation.

Map of group settlements locations on the Navajo Nation, 2010. The green area inside the Navajo Nation is actually the Hopi Reservation: it's a land of about 1.5 million acres (approximately 607,000 hectares) surrounded entirely by the Navajo Nation. A population of 7,791 Hopi and Arizona Tewa people live here, according to the 2020 Census.

Under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0Unported license.

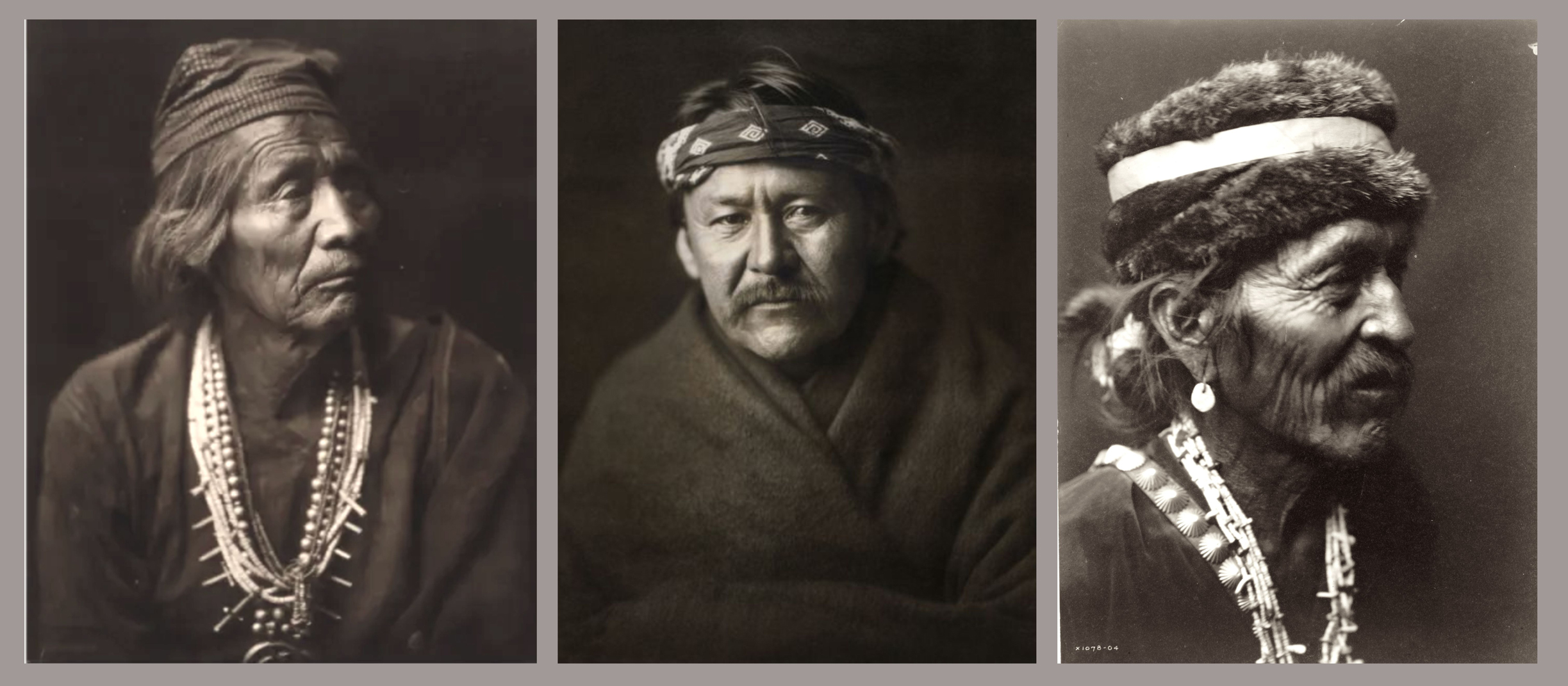

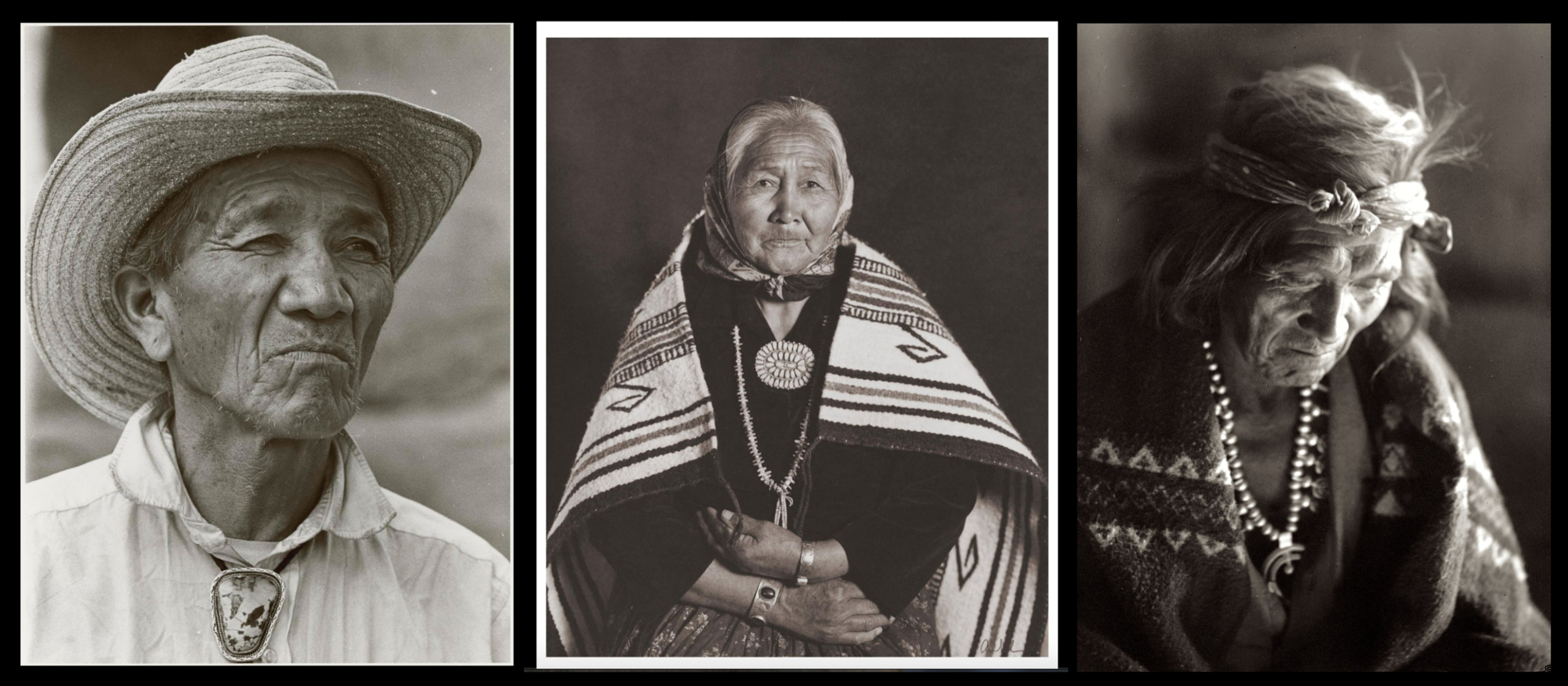

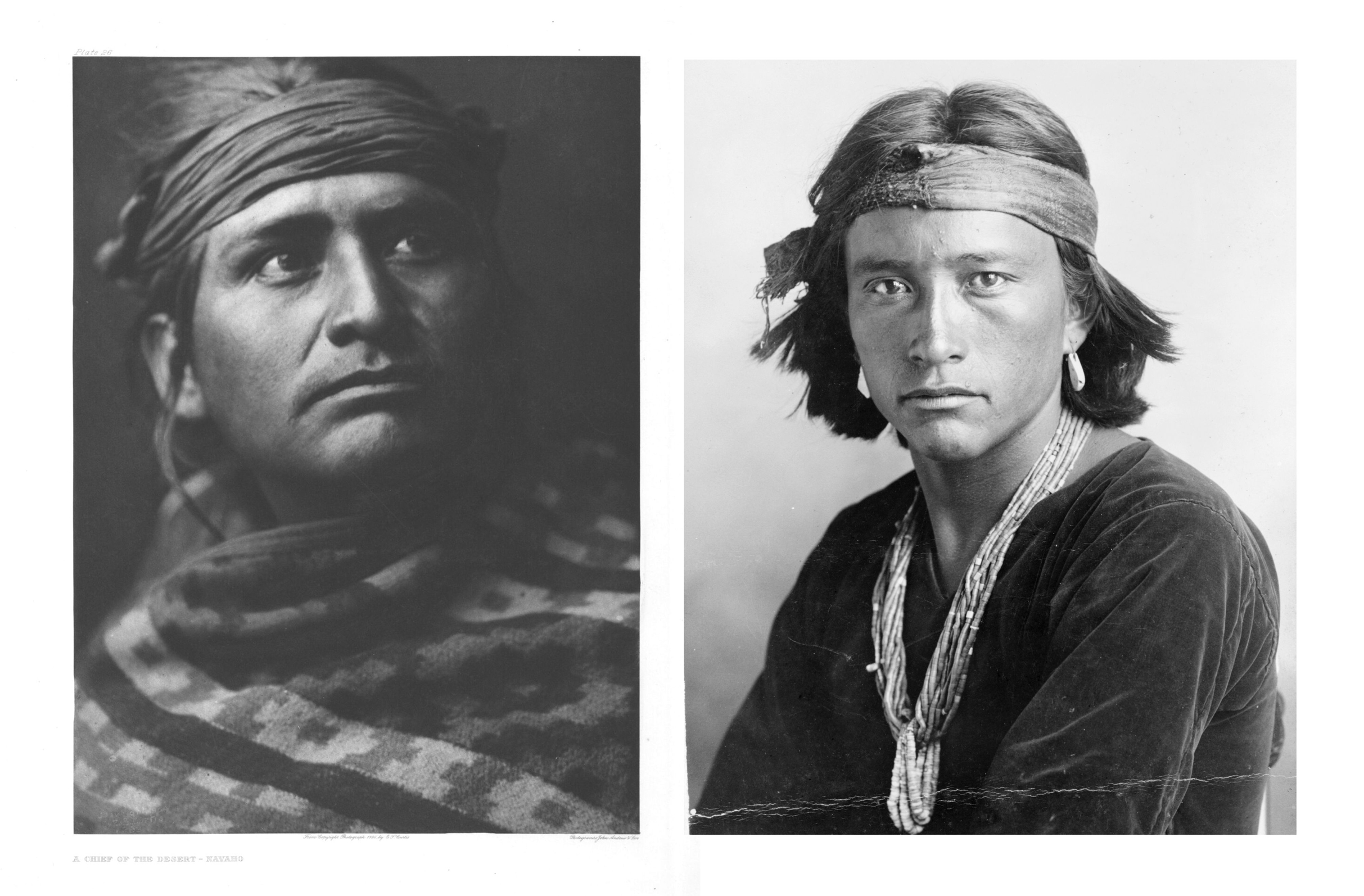

LEFT: Nesjaja Hatali, Navajo, ca. 1904. Photo by Edward Sheriff Curtis. Source: Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, Washington D.C., USA

CENTER: A Navajo man wearing a blanket and headband, ca. 1904. Photo by Edward Sheriff Curtis. Public Domain.

RIGHT: Navajo with fur cap, early 19th century. Photo by Edward Sheriff Curtis. Public Domain.

LEFT: Portrait of Navajo Medicine Man, Sonny Claus Chee, 1979. Abigail Adler Diné (Navajo) photographs, NMAI.AC. National Museum of the American Indian Archive Center, Smithsonian Institution, USA.

CENTER: Ruth Benally wearing a blanket, 1993. Photo by Gary Auerbach. National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution, USA.

RIGHT: Studio portrait of Peshcliklime (Bah-Ulth-Chin-Thlan), an elderly Navajo man, ca. 1900-1938. Photo by William M. Pennington, Denver Public Library Special Collections, [call number X-32968], CO, USA.

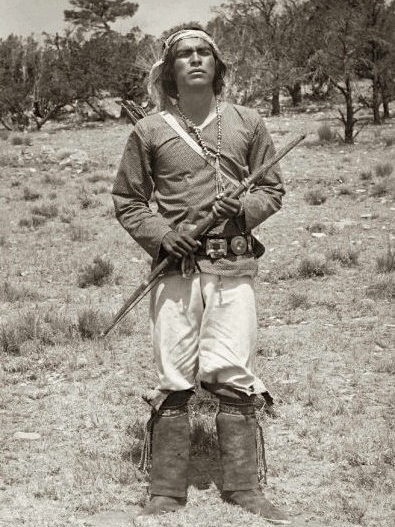

LEFT: Navajo man, ca. 1900-1910. Photo by Edward Sheriff Curtis. Denver Public Library Special Collections [call number X-34027], CO, USA.

RIGHT: Navajo boy, ca. 1906. Photo by Carl Moon. Source: Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C., USA.

EARLY 20th CENTURY

Formation of the Navajo Nation

In 1923, the Navajo Tribal Council was established, marking a significant step toward self-government and autonomy. This body served as the foundation for the current government of the Navajo Nation.

Indian Reorganization Act (1934)

he Navajo Nation strongly opposed the Indian Reorganization Act of 1934. This act was intended to reverse previous policies that had led to the loss of land among Native American tribes and to encourage the adoption of constitutions and bylaws to strengthen self-government. However, due to concerns about livestock reduction programs and other issues, the Navajo chose not to adopt the act. I know: this rejection seems incomprehensible, but we'll come back to it because this event has to do with the other protagonist of our stories besides the Navajo people: the Navajo Churro sheep.

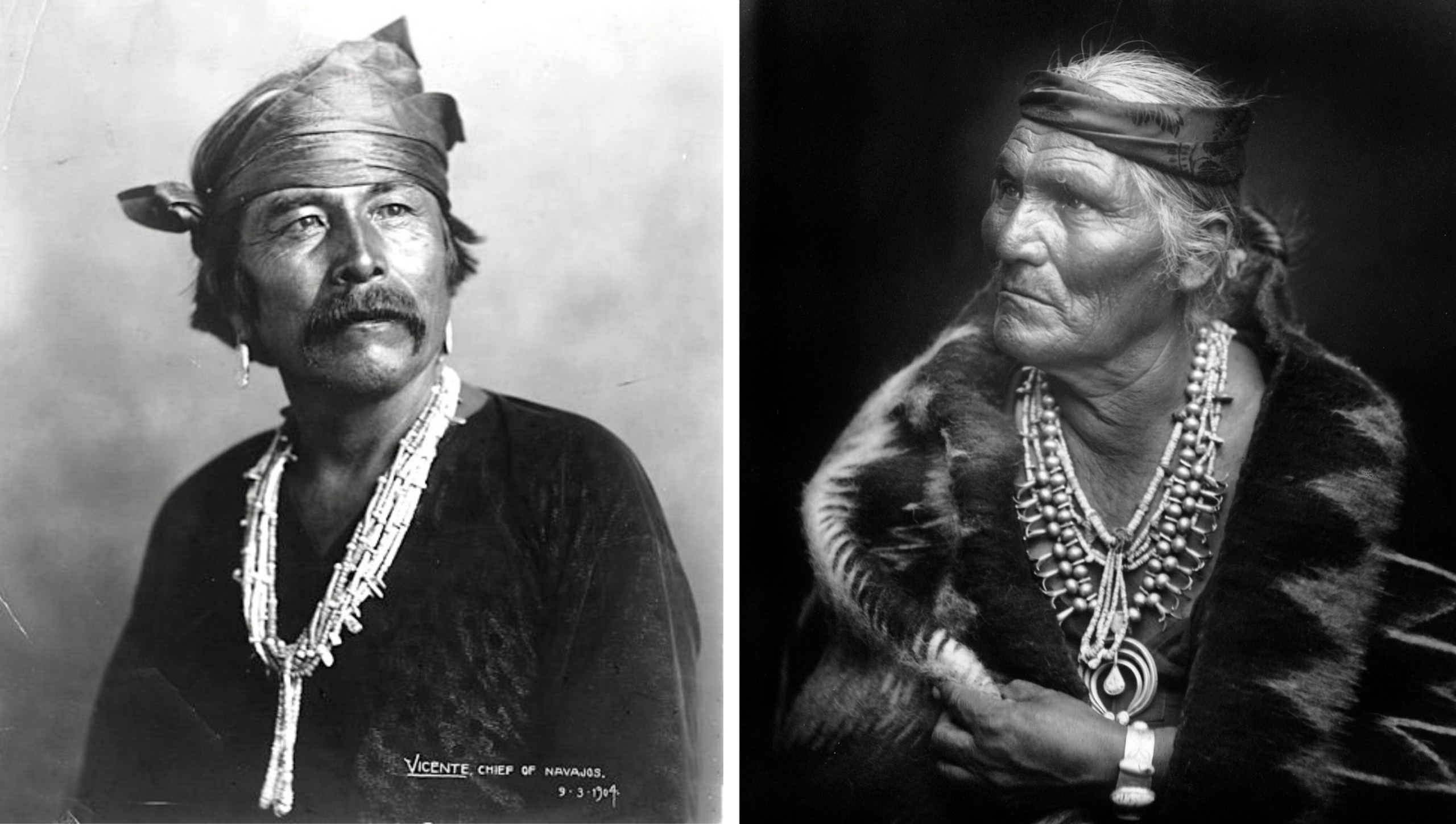

LEFT: Chief Vicente, 1904, photo by Carl Moon, Public Domain.

RIGHT: Studio portrait of Judge Klah, Navajo Judge, Justice of the Peace, ca. 1900-1938. Photo by William M. Pennington.Source: Denver Public Library Special Collections, [call number X-32997], CO, USA.

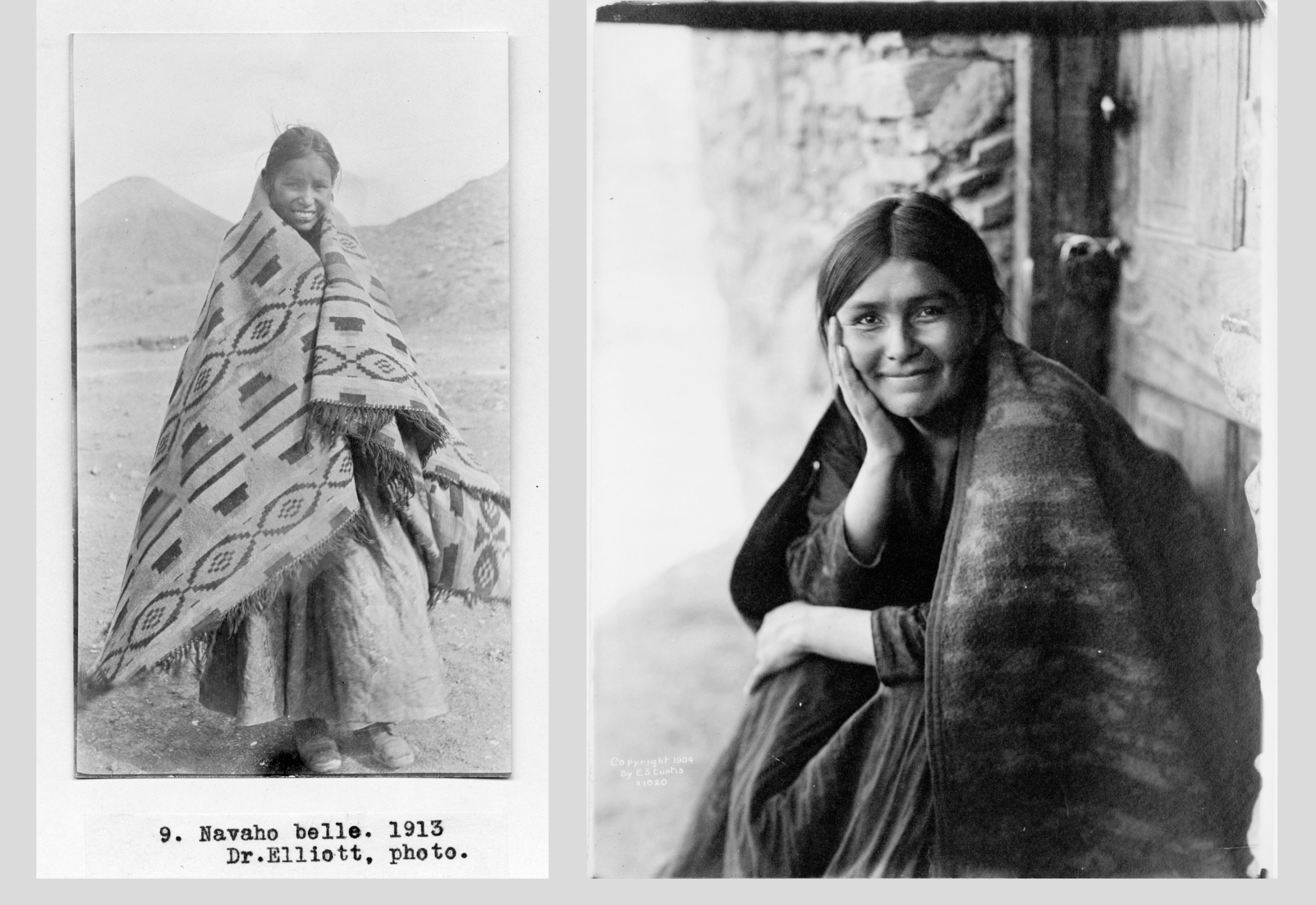

LEFT: Navajo girl, photo taken by D. S. Elliott in 1909 and published in Herbert Ernest Gregory, Book 3: Navajo-Hopi, Arizona-

New Mexico, 1913. Source: J. Willard Marriot Digital Library, University of Utah, USA.

RIGHT: Navajo girl, early 19th century. Photo by Edward Sheriff Curtis. Public Domain.

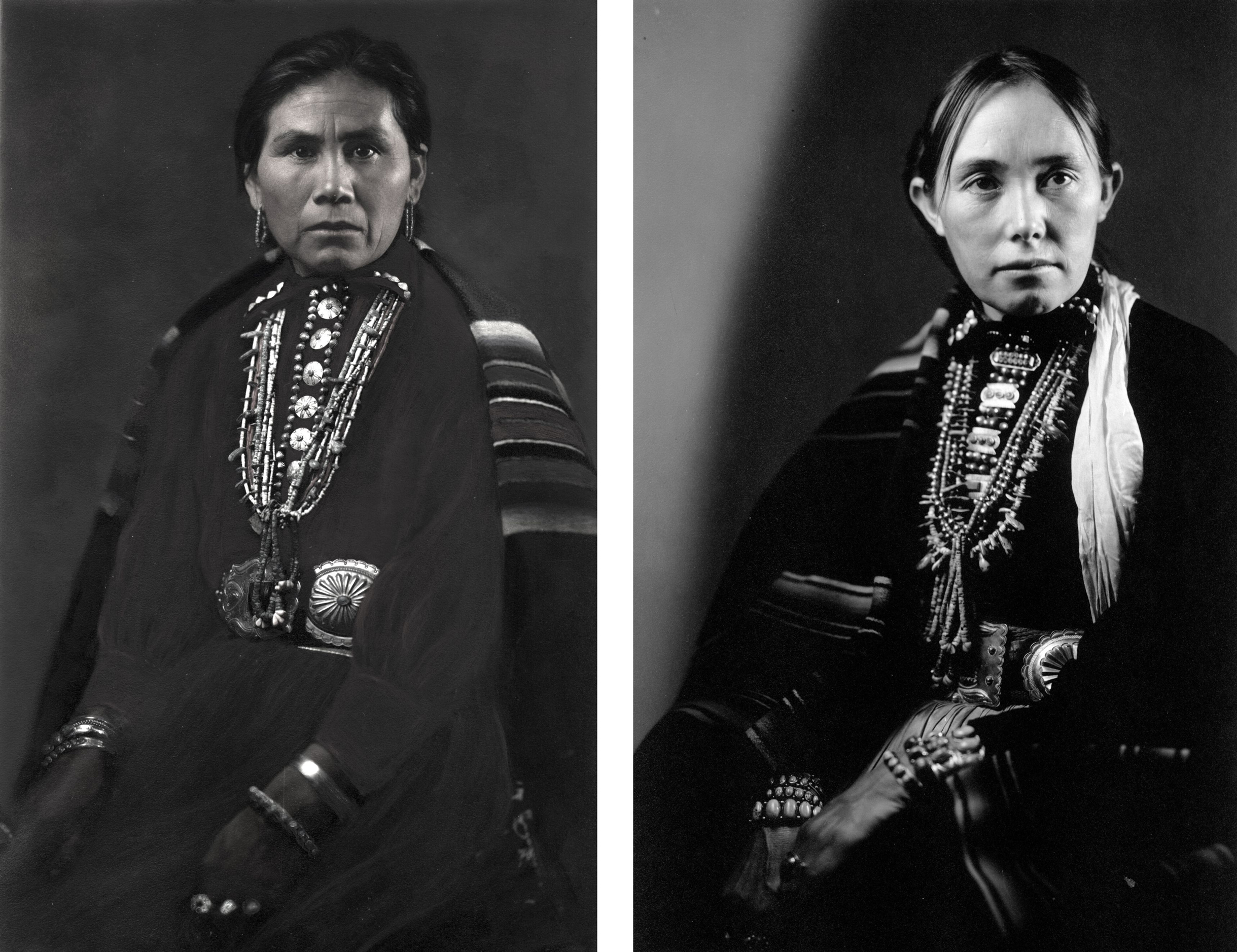

Both pictures are studio portraits of Navajo women. Source: Denver Public Library Special Collections, [call numbers X-32154 and X-32156], CO, USA. These photos were taken by Talcott Harmon Parkhurst (1883/1952); they are not dated but probably were printed in the 1910s or 1920s.

MID-20th CENTURY

World War II Contributions

During World War II, Navajo Code Talkers played a crucial role in the Pacific Theater by using the Navajo language to transmit secure military communications. Their unbreakable code was instrumental in several Allied victories and helped raise raise awareness of Navajo culture.

Code Talkers - Pritzker Military Museum & Library

«The Code Talkers are remembered for transmitting more than 800 messages in the Navajo language without a single error in battles in the South Pacific. Many of these Code Talkers never returned to their families.», Navajo Nation President Buu Nygren.

Navajo Code Talkers by Associated Press

Ongoing struggles for autonomy

Despite these advances, the Navajo continued to face challenges related to land rights, resource management, and cultural preservation. Issues such as uranium mining led to health and environmental concerns, highlighting the complexities of maintaining autonomy while dealing with outside economic interests.

LEFT: Navajo girl, photo taken by D. S. Elliott in 1909 and published in Herbert Ernest Gregory, Book 3: Navajo-Hopi, Arizona-

New Mexico, 1913. Source: J. Willard Marriot Digital Library, University of Utah, USA.

RIGHT: Navajo girl, early 19th century. Photo by Edward Sheriff Curtis. Public Domain.

LEFT: Navajo girl, photo taken by D. S. Elliott in 1909 and published in Herbert Ernest Gregory, Book 3: Navajo-Hopi, Arizona-

New Mexico, 1913. Source: J. Willard Marriot Digital Library, University of Utah, USA.

RIGHT: Navajo girl, early 19th century. Photo by Edward Sheriff Curtis. Public Domain.

LATE 20th CENTURY

Indian Civil Rights Act (1968)

This act extended certain civil rights protections to individuals within Native American tribes, including the Navajo, ensuring protections similar to those found in the U.S. Bill of Rights.

Indian Self-Determination and Education Assistance Act (1975)

This legislation empowered tribes by giving them greater control over their own affairs, including the administration of education and health programs.

Cultural Preservation Efforts

The late 20th century saw increased efforts to preserve Navajo culture, language, and traditions. Initiatives included educational programs and cultural projects aimed at preserving and revitalizing Navajo identity.

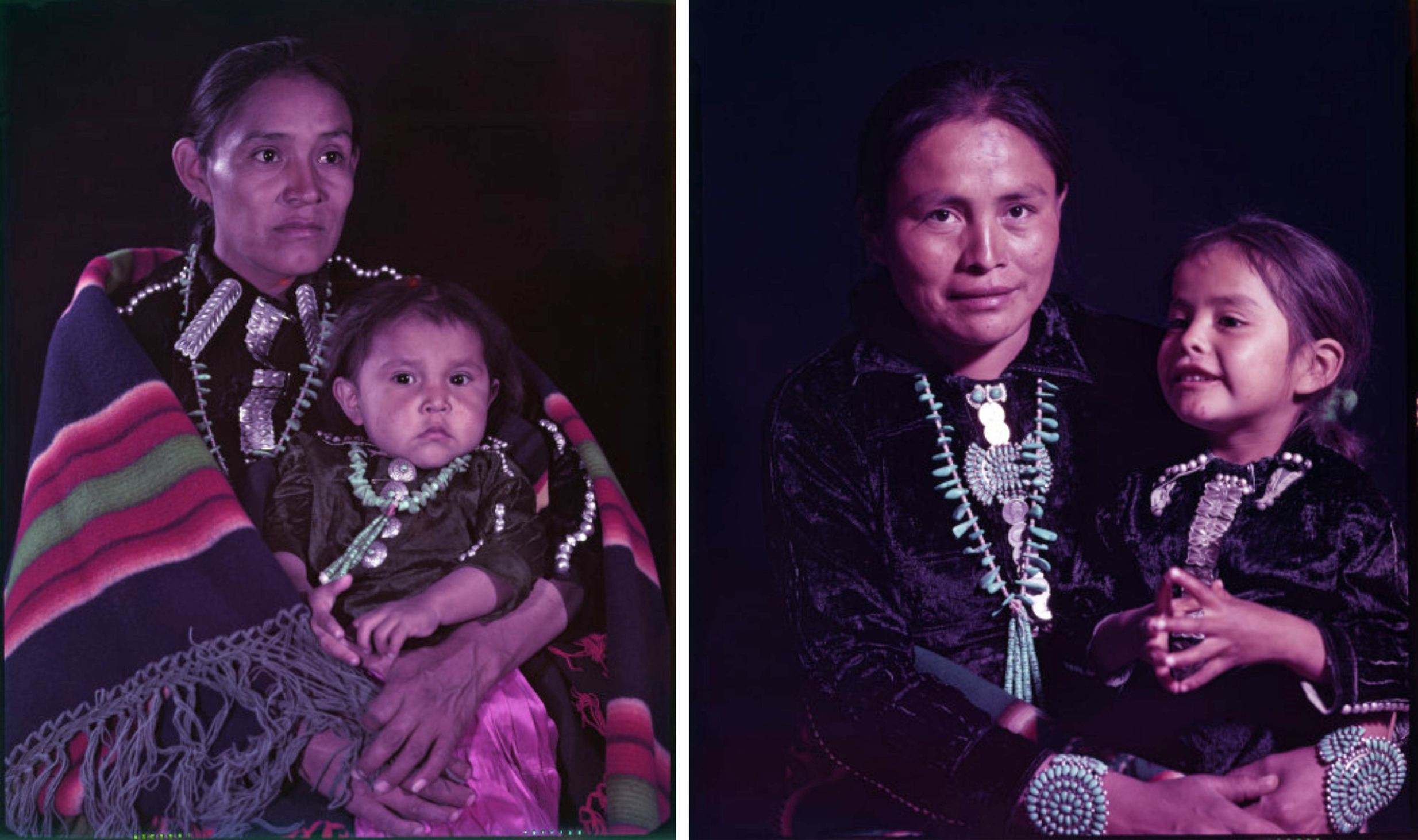

Three generation of Navajo women. ©Getty Images.

THE PREDATORY FACE OF POSTMODERN COLONIALISM:

URANIUM MINING ON THE NAVAJO NATION IN THE 20th CENTURY

From the Manhattan Project to the Cold War Era

Uranium mining on Navajo lands began in 1944 in northeastern Arizona, northwestern New Mexico, and southeastern Utah as part of the Manhattan Project. After World War II, uranium ore was discovered in the Lukachukai Mountains near Cove and Red Valley, Arizona. In 1948, the U.S. Atomic Energy Commission (AEC) announced that it would guarantee a price and purchase all uranium ore mined by private companies in the United States, sparking a mining "boom" on the Colorado Plateau, in New Mexico, Utah, Colorado, and Arizona.

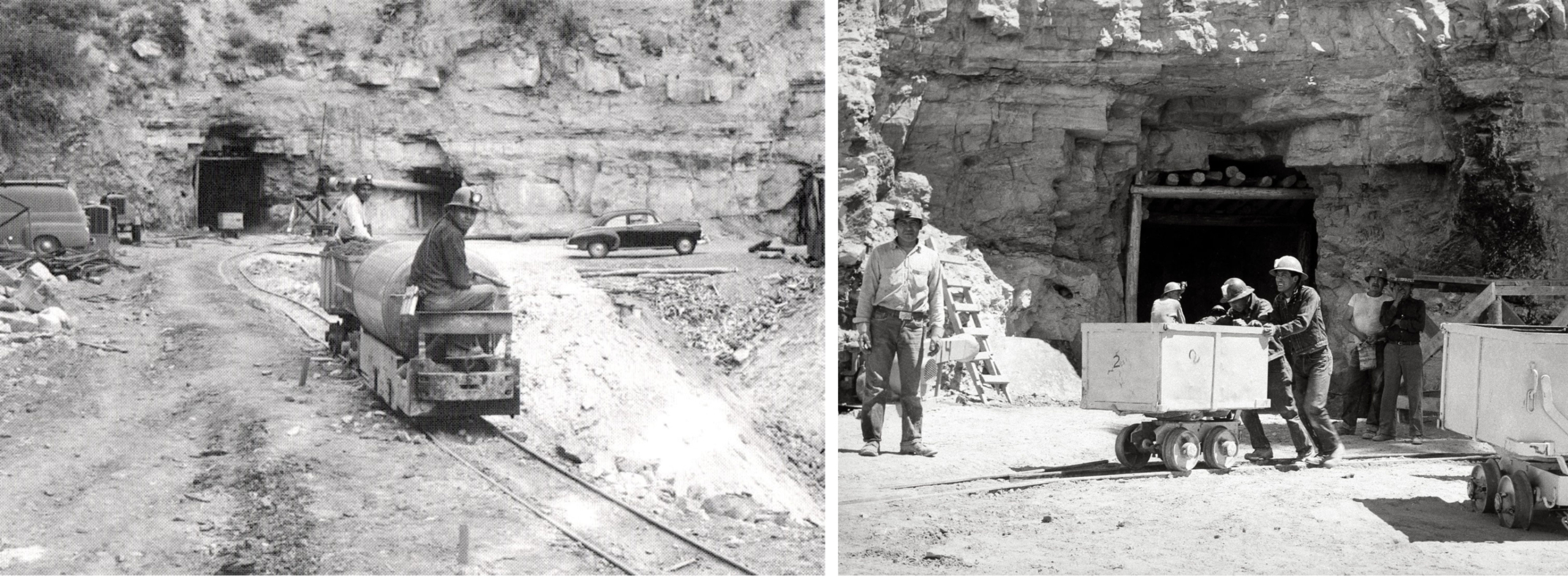

The Kerr-McGee Corporation began mining operations in the Red Valley area in 1952, opening the Cove and Mesa mines on the Navajo Reservation. However, other companies such as the Vanadium Corporation of America and Phillips Petroleum were also major players in early uranium mining efforts. Mining operations peaked in 1955 and 1956 during the height of the Cold War. During this time, the Navajo Nation was located directly in the uranium mining belt and many residents found work in the mines.

LEFT: Navajo miners near Cove, Arizona in 1952. Photo by Milton Jack Snow, courtesy of Doug Brugge/Memories Come To Us In the Rain and the Wind.

RIGHT: Navajo miners work at the Kerr-McGee uranium mine near Cove, Arizona, on May 7, 1953. © Associated Press

By 1958, there were 7,500 reports of uranium discoveries in the United States, with more than 7 million tons of ore identified. At its peak in the mid-1950s, there were about 750 mines in operation (Eichstaedt PH., Brugge, and Goble). According to the Center for Public Integrity, private companies mined an estimated 30 million tons of uranium ore on or near the Navajo Nation from 1944 to 1986, mostly for the U.S. government's nuclear arsenal and, in later years, for commercial purposes. They left a trail of radioactive waste that, nearly 80 years after the work began, remains largely unremediated and continues to cause harm, according to the Navajo Nation Environmental Protection Agency. The last mine closed in 1990, and there are now an estimated 523 abandoned uranium mine shafts on Navajo land (A Call for Justice, The Navajo Nation).

But let's take it one step at a time.

Navajo Miners

From 1944 to 1986, an estimated 3,000 to 5,000 Navajo people worked in the uranium mines on their land (Fettus, G.H. and M. G. Mckinzie).

« Navajo men gravitated to work in the mines, which were near their homes and about the only job available. For many Navajo families, uranium mining represented a first contact with the broader US wage economy. These Navajo families were thankful at the time that they had employment.

Miners were paid minimum wage or less. (...) The jobs that they held included blasters, timber men (building the wooden supports in the mines), muckers (who dug the blasted rock), transporters, and millers. Navajo miners report that the bosses were usually White.» (Brugge and Goble)

Health Impacts and Lack of Protection

Navajo miners were kept in the dark about the dangers of radiation exposure.

«The Navajo language had no word for radiation, few Navajo People spoke English, and few had formal education. Thus, the Navajo population was isolated from the general flow of knowledge about radiation and its hazards by geography, language, and literacy level. (...) They had no idea that there were longterm health hazards associated with uranium mining. Virtually all of the Navajo miners report that they were not educated about the hazards of uranium mining and were not provided with protective equipment or ventilation.» (Brugge and Goble)

And yet, the environmental risks and irreversible health damage associated with uranium mining were well known at the time. The CEOs and executives of the mining companies knew this very well, as several studies had already suggested links between uranium mining and lung disease.

The very first studies on the subject were done in Germany in 1879 (F.H. Härting and W. Hesse) and by the 1920s, European researchers studying miners in Germany and Czechoslovakia found an increased risk of lung cancer due to radon exposure. By 1932, Germany and Czechoslovakia had designated cancer in uranium miners as a compensable occupational disease. Thus, «by the late1930s there was no scientific doubt that uranium mining was associated with high rates of lung cancer» (Brugge and Goble). However, this information was not shared with the Navajo miners. None of them were informed. Many of these miners worked in poorly ventilated conditions that exposed them to radioactive uranium dust, radon gas, and fine silica. Smaller mines, in particular, lacked adequate ventilation systems, exacerbating the risks of exposure. As a result, many miners developed serious respiratory illnesses and cancers.

The U.S. Public Health Service (PHS) began a controversial study of uranium miners on the Colorado Plateau in 1950. This study included both white and Navajo miners, with approximately 4,000 Navajo uranium miners participating. This medical study began without the informed consent of the miners involved, in violation of the 1947 Nuremberg Code, which emphasized the importance of informed consent in research.

If the environmental part of the study began in 1950, the systematic epidemiologic studies began in 1954. The miners were not informed of the potential health risks of uranium mining or that they were part of a study. In 1959, the study showed a statistically significant association between uranium mining and lung cancer for white miners. However, minority miners who participated in the field study were initially excluded from the report. As late as 1960, the PHS medical consent form still failed to inform Navajo miners of the potential health risks of working in the mines.

Despite this growing body of evidence, Navajo miners continued to receive little to no warning of health hazards in the 1960s. As late as 1971, workers attending mining training programs were not informed of the risks associated with uranium exposure.

Moreover, uranium contamination was not limited to miners. Many Navajo families lived near mines, mills, and waste dumps, where they were exposed to airborne and waterborne radiation. In addition, "downwinders" - individuals living near nuclear test sites-also faced increased cancer risks due to atmospheric nuclear testing in the region.

An employer who knowingly endangers workers by withholding critical health and safety information could potentially be found guilty of criminal negligence.

In addition, conducting medical research without informed consent is a violation of several laws, as it violates the legal and human rights of patients.

Environmental Contamination and Legacy

The Navajo Nation was the site of one of the worst radioactive accidents in U.S. history: the 1979 Church Rock uranium mill spill. A breach in a tailings pond dam released 93 million gallons of radioactive wastewater into the Puerco River, contaminating drinking water sources, harming livestock, and causing long-term health risks to nearby communities.

The Northeast Church Rock Mine is a former uranium mine located at the north end of State Highway 566 approximately 17 miles northeast of Gallup, NM in the Pinedale Chapter of the Navajo Nation. Today, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) is working with the Navajo Nation Environmental Protection Agency (NNEPA) to oversee cleanup efforts by United Nuclear Corporation (UNC), a company owned by General Electric (GE). Pictured here is part of the Northeast Church Rock Mine in 2009.

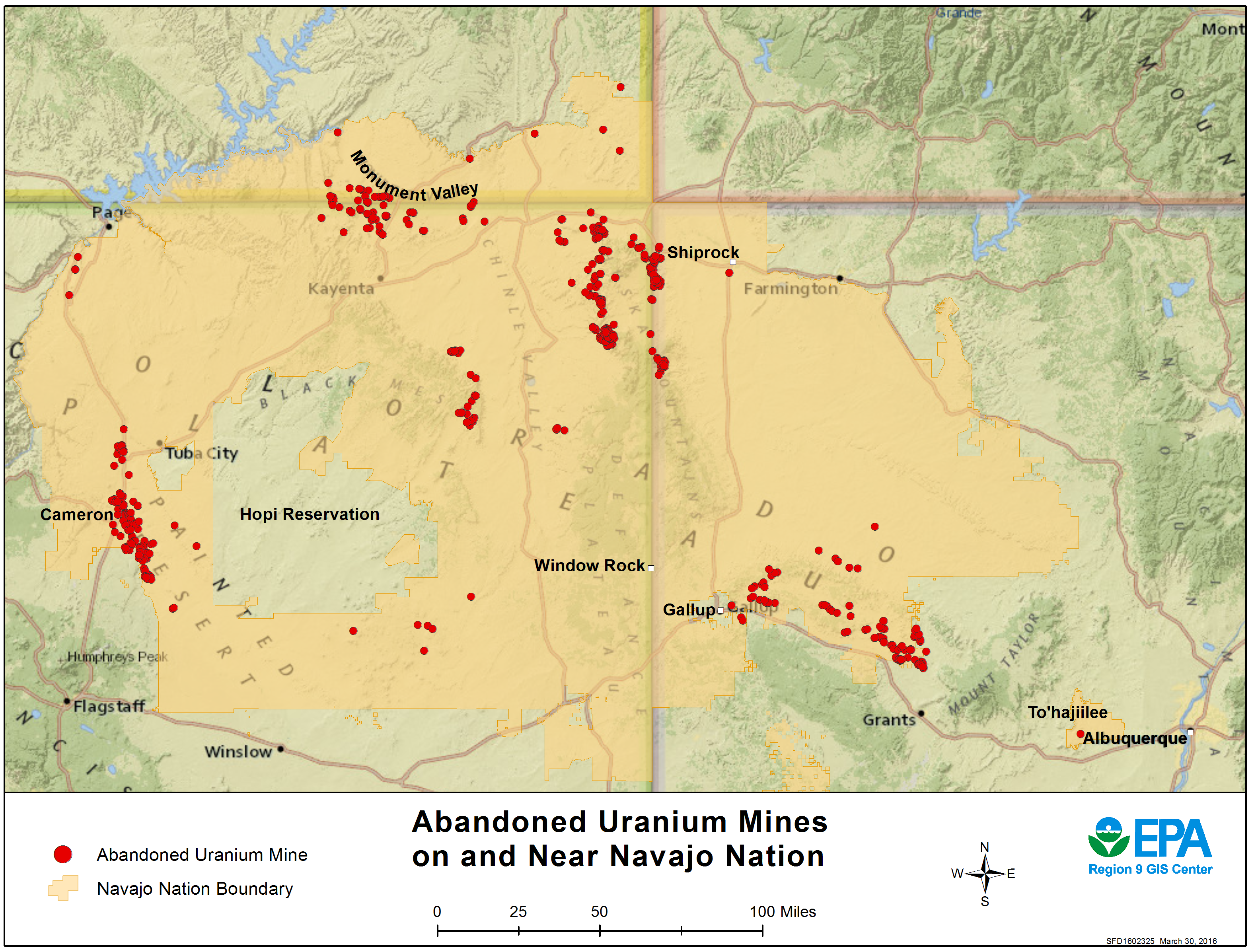

Today, the Navajo Nation continues to suffer from uranium contamination. According to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), more than 500 abandoned uranium mines (AUMs) remain, and many homes and water sources still contain elevated levels of radiation. A 2008 study found uranium contamination in 29 water sources across the Navajo Nation, and other studies indicate that people living near waste sites have an increased risk of kidney disease and various cancers.

Map of abandoned uranium mines on and near Navajo Nation. By United States Environmental Protection Agency.

While uranium mining has contributed to environmental hazards, other factors such as government neglect and infrastructure challenges have also played a role in the Navajo Nation's lack of access to clean water. Currently, approximately 15% of the Navajo population does not have running water, forcing some residents to rely on unregulated sources that may contain uranium and other contaminants.

In response to the environmental devastation, several uranium-contaminated sites on the Navajo Nation have been designated as Superfund sites by the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), allowing for federal cleanup efforts.

Remediation Efforts and Recent Developments

In the 1960s, when the first cases of lung cancer began to appear among the Navajo uranium miners, many widows «came together and talked about their husband’s deaths and how they had died. The process that they initiated, which included steep learning curves about science, politics, and organizing, would culminate some 30 years later in the passage of the RECA.» (Brugge and Goble)

In 1990, Congress passed the Radiation Exposure Compensation Act (RECA) to provide financial relief to individuals affected by uranium exposure. Navajo uranium miners and ore haulers received some of the highest compensation amounts, up to $100,000 per claim.

The EPA has secured more than $1.7 billion in settlements to reduce the risks of radiation exposure to Navajo communities. These funds have been used to assess and clean up 230 of the 523 abandoned uranium mines.

The 2014 Tronox settlement, which stemmed from a bankruptcy case, provided $5.15 billion for cleanup efforts across the United States. Of that amount, $1 billion was earmarked for the cleanup of 50 uranium mines on the Navajo Nation.

How the US poisoned Navajo Nation, by Vox, 2020

Recent Developments (2025)

On January 29, 2025, Energy Fuels and the Navajo Nation announced an agreement for the transportation of uranium ore, which resumed in February 2025. The agreement governs the transportation of uranium ore on federal and state highways across the Navajo Nation.

As part of the agreement, Energy Fuels has committed to accept and transport up to 10,000 tons of uranium-bearing reclamation material from abandoned uranium mines at no cost to the Navajo Nation. The company has also pledged additional support for transportation safety programs, education, environmental protection, public health initiatives and local economic development efforts related to uranium issues.

However, some Navajo community advocates have expressed concern about the lack of public involvement in the decision-making process. Specifically, they question how potential radioactive spills would be handled and how safety measures would be enforced.

The Radiation Exposure Compensation Act (RECA) legislation expired in 2024, leaving many victims without compensation; it's is still stalled in 2025, despite multiple attempts to reauthorize and expand it.

Supporters of the Radiation Exposure Compensation Act sing about saving the program on Sept. 22, 2024, before leaving Albuquerque, New Mexico for Washington, D.C. Credit: Noel Lyn Smith/Inside Climate News.

TWO FINAL THOUGHTS

The history of uranium mining on the Navajo Nation is a complex tale of economic exploitation, environmental devastation, and long-term health impacts. While significant cleanup efforts are underway, the Navajo people continue to deal with the aftermath of decades of unregulated uranium mining. Ongoing community advocacy and federal cleanup efforts will be critical to addressing the remaining contamination and ensuring the safety of future generations.

«This history details how the federal government deliberately avoided dealing with a health disaster among Navajo uranium miners.» (Brugge and Goble). But most of all, this history tells us how the Cold War race for nuclear armament, the pursuit of profit at any cost, racism and systematic discrimination against an ethnic minority led to an environmental disaster whose effects are still being felt; to the systematic violation of the human and legal rights of the Diné people; and to the exploitation of the land and its natural resources according to an unsustainable and environmentally destructive model.

I titled this section "The Predatory Face of Post-Modern Colonialism". The history of uranium mining on the Navajo Nation during the 20th century shows us one of the contemporary forms of postmodern colonialist domination and exploitation operating in a globalized, fragmented world.

Why Colonialism? you may ask. After all, the Navajo Nation is not a foreign and completely independent state within the United States. So legally and strictly speaking, one shouldn't talk about neocolonialism or post-modern colonialism. However this history reveals how the US government adopted that typical neocolonial control of the mother country over the "decolonized" land, influenced by the legalistic continuation of economic, cultural, and linguistic power relations. Neither the United States government and its 'extensions', nor the private mining companies have sought the cooperation and collaboration of the Navajo Nation. The prevailing attitude has been predatory and has given rise to a colonial-type exploitation impregnated with not-so-hidden supremacist racism. The relation between the US government agencies and private companies on one side and the Navajo Nation on the other was a relation of domination and subservience. Let's look at two aspects of this history.

- Permission from the Navajo Nation

Historically, uranium mining companies have not always received the full consent of the Navajo Nation as a governing entity. Mining activities were largely driven by the U.S. government's demand for uranium during World War II and the Cold War. Many leases were signed with individual Navajo allottees under the General Allotment Act (Dawes Act of 1887), which had divided communal tribal lands into private parcels. However, uranium mining on these lands was more directly facilitated by the Indian Mineral Leasing Act of 1938, which allowed private companies to negotiate mineral leases on Native American lands with the approval of the U.S. government.

These agreements often lacked transparency and did not provide fair compensation to Navajo landowners. Many Navajo allottees leased their land without fully understanding the risks, as information about the dangers of uranium exposure was not disseminated. In addition, the broader Navajo Nation government was often excluded from decision-making, allowing large-scale mining operations to proceed without proper tribal consultation.

- Distribution of Profits

Profits from uranium mining on Navajo lands primarily benefited mining companies and the U.S. government, while Navajo communities saw little economic benefit and suffered long-term health and environmental impacts. From 1944 to 1966, the U.S. Atomic Energy Commission (AEC) was the sole purchaser of uranium, ensuring a stable and profitable market for mining companies.

Navajo uranium miners were paid minimal wages and worked in hazardous conditions without proper ventilation or protective equipment, resulting in high rates of lung cancer and other diseases. Royalties paid to Navajo allottees and the Navajo Nation were extremely low - often as low as 3.4% of market value - while companies reaped substantial financial benefits.

The Navajo Nation government itself did not receive significant economic benefits from uranium mining, but the legacy of contamination and health problems continues to affect Navajo communities. High levels of radiation exposure, contaminated water sources, and abandoned uranium mines remain serious challenges even today.

The political fragility of the Navajo Nation is evident even today, perhaps even more than in the past, and this is not just a Navajo problem. It is something that concerns all of us. And this brings us directly to the second thought that I hope will get your attention. It's important to me.

By contaminating the water, soil, and air, this blind and senseless exploitation not only brought a slow death sentence to the miners and their families, but also indirectly threatened the survival of the Diné people by damaging their agricultural resources, decimating their herds and flocks, and jeopardizing the resources derived from international tourism. The Diné people, their identity, their centuries-old traditions and culture have been endangered, and this is not just a crime against the Diné. It's a crime against you and me as well, because it's a crime against all of humanity.

Any attempt at forced standardization and assimilation, any predatory attitude toward an ethnic group or community that threatens not only its survival but its very ability to thrive, is a threat to human diversity and should be considered a crime against all of humanity.

Why?

For the Olympic Games in Rio 2016, Brazilian artist Eduardo Kobra created the world's largest graffiti. The mural, titled Etnias ('Ethnicities'), was painted on a vast 190-meter-long wall, 15.5 meters high, located in the restored port area of Rio de Janeiro. Five indigenous faces from five continents represent the five Olympic rings and symbolize the multi-ethnicity of the Olympic games and racial integration.

LET'S TALK ABOUT HUMAN DIVERSITY

Human diversity is indeed a richness for humanity, but it goes beyond being merely beneficial—it seems to be a necessary condition for human development and evolution.

Genetic diversity is an evolutionary necessity

Evolutionary biology emphasizes genetic diversity as critical to the survival and adaptability of any species, including humans. Genetic variation provides a pool of different “solutions” that allow populations to cope with changing environments, disease, and other threats. Studies have shown that species with greater genetic diversity are more resilient: «When a species has different genetic solutions, it’s better able to deal with changes… Higher genetic diversity also means there’s a greater chance of a species’ survival.» (Many animals and plants are losing their genetic diversity, making them more vulnerable). Conversely, low diversity (e.g. due to inbreeding or population bottlenecks) makes a species vulnerable to extinction from new diseases or environmental changes (Many animals and plants are losing their genetic diversity, making them more vulnerable).

From an evolutionary perspective, genetic diversity has been critical to human adaptation and survival. Research shows that African populations tend to have higher levels of genetic diversity, which has implications for understanding human evolutionary history. This diversity has allowed humans to adapt to different environments and challenges throughout our evolutionary journey and has been key to our species' resilience and adaptability in the face of challenges.

In humans, genetic diversity has played a remarkable role in our evolutionary success. Although humans are less genetically diverse than many other species (due to a common origin in Africa and periodic bottlenecks), even small amounts of additional diversity have had significant effects. For example, when modern humans migrated into Eurasia ~50,000 years ago, they interbred with Neanderthals and acquired genetic variations that proved advantageous. Researchers have found that certain Neanderthal-derived genes in modern humans «provided immediate benefits, such as helping humans adapt to new climates as they migrated out of Africa.» (How Neanderthal DNA influenced human survival) These genes affected traits such as skin pigmentation, metabolism, and immune function, illustrating how mixing different gene pools enhanced human adaptability. In short, from an evolutionary standpoint, diversity in our DNA (and in the DNA of the organisms we depend on) is not a luxury, but a necessity for long-term survival. Genetic diversity is the raw material of natural selection and a cornerstone of adaptability in the face of planetary change. (Many animals and plants are losing their genetic diversity, making them more vulnerable).

Detail from Etnias by Eduardo Kobra, Rio, Brazil. Photo by Kasia Halka, 2018.

«Cultural diversity is as necessary for humankind as biodiversity is for nature»

This statement, contained in the Universal Declaration on Cultural Diversity (2001) of the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), recognizes cultural diversity as a common heritage of humanity and an inseparable principle of human rights, citizenship and fundamental human freedoms. The powerful comparison between biodiversity and cultural diversity suggests that just as the former is essential for ecosystem functioning, cultural diversity is necessary for human social systems to develop and thrive. The immense wealth of cultural diversity accumulated over millennia is considered more than vital to human social and economic development, because it is the condition that makes that development possible.

In other words, the evidence suggests that diversity is not only enriching but fundamental to human development. Just as a diverse ecosystem is more resilient to environmental change, human diversity-genetic, cultural, cognitive, and experiential-provides our species with the adaptability needed to meet challenges and evolve.

Thus, if genetic diversity is an evolutionary necessity, cultural diversity is a condition of possibility for human survival, adaptation, and progress.

The different perspectives, skills, and approaches that come from our differences have enabled innovations that would be impossible in a homogeneous population. This suggests that diversity is indeed a condition of possibility for humanity's continued development and evolution, providing the raw material for the adaptation and innovation that drives our progress as a species.

Details from Etnias by Eduardo Kobra, Rio, Brazil

Anthropology and Cultural Evolution: Diversity as Adaptive “Survival Kit”

Anthropologists and scholars of cultural evolution emphasize that humans adapt to their environment largely through culture (learned behaviors, knowledge, and technology), and that cultural diversity therefore provides a vital repertoire of adaptive strategies. Unlike other animals, humans don't rely solely on slow genetic evolution for survival; we use cumulative cultural learning over generations. In fact, a broad comparative study found that «the primary mode of human adaptation is social learning mechanisms that operate over multiple generations» rather than genetic changes alone. (Behavioural variation in 172 small-scale societies indicates that social learning is the main mode of human adaptation - PubMed). This means that humanity's ability to thrive in virtually every ecosystem-from the Arctic tundra to the desert-is the result of different cultural solutions (clothing, shelter, hunting techniques, etc.) developed by different groups. Each society's innovations add to our species' collective toolbox.

Human culture is extraordinarily diverse, encompassing thousands of languages, technologies, and social customs. Psychologists argue that our species' unique cognitive flexibility underlies this cultural diversity: «Human culture is uniquely variable in nature, as exemplified by the extraordinary diversity of skills and practices (…) Human psychological flexibility provides the foundation for cultural diversity and is a prerequisite for cumulative culture.» ( Cumulative cultural learning: Development and diversity - PMC ). In other words, our ability to invent, learn, and change strategies enables the proliferation of diverse traditions and technologies, which in turn allows us to build increasingly complex knowledge systems. This cumulative culture - built incrementally by many people over time - is what has made humans so successful, and it inherently depends on having variation (multiple ideas, experiments, and experiences to draw from). Researchers note that cultural transmission is the "cornerstone" of human diversity, and that children everywhere acquire the specific practices of their community through social learning, ensuring continuity and variability across populations. ( Cumulative cultural learning: Development and diversity - PMC ).

Critically, cultural diversity acts as an insurance policy or "survival kit" for humanity. Different cultures hold unique knowledge - especially indigenous and local knowledge finely tuned to specific environments - that can be critical in times of change. As one sustainability science report put it, «when languages become extinct, associated knowledge is often lost… our collective ‘survival kit’ is becoming depleted.» (Biocultural Diversity | SwedBio). Conversely, maintaining a rich tapestry of cultures and knowledge systems increases our species’ abilty to solve problems and adapt. Indeed, experts now argue that biocultural diversity (the intertwined diversity of cultures and ecosystems) «provides innovative ways of coping with global change» and will be increasingly important for resilience as we face climate and ecological crises (Biocultural Diversity | SwedBio). In summary, anthropology shows that cultural diversity is not just an ornament of human life, but the very mechanism by which Homo sapiens overcame challenges and evolved into the most adaptable species on the planet.

Celebrating Global Unity at Wynwood Walls, Mural by Eduardo Kobra, Wynwood Walls, Miami, Florida, USA. Photo by jpeligen.

BELOW

Detail, Mural by Eduardo Kobra, Wynwood Walls, Miami, Florida, USA.

Philosophy and Ethics: The Fundamental Value of Difference

Philosophers and ethicists have also come to see human difference and plurality as fundamental to our existence and moral life. Traditional humanism often emphasized human commonality, but contemporary thought (influenced by postmodern and postcolonial perspectives) emphasizes that «diversity is the reality through which any universal human values must express themselves.» Rather than seeing diversity as an obstacle to be overcome, many modern philosophers see it as essential to meaning, dialogue, and ethics. Postmodern philosophy in particular «celebrates differences» and resists the imposition of a single, uniform narrative on human life (Uniformity vs Diversity. When Modern philosophy emphasises… | by arun simon | Medium). The very notion of truth and understanding, in this view, is inherently dialogical: it emerges from the interaction of different perspectives. We expand knowledge by engaging with those who see the world differently, which requires valuing diversity of thought and identity.

Ethicists argue that recognizing the full humanity of others in their diversity is a moral imperative. Diverse others are not merely to be tolerated, but are in some sense necessary for us to realize ourselves fully. As one humanist philosopher has put it: «The foundational value, the overriding principle of [a global culture], needs to be the preservation of the Other. As Patricia Hoertdoerfer wrote, the hallmark is coexistence: in the preservation of the other is the condition for the preservation of the self. We are not we until they are they; for to whom else shall we speak, with whom else shall we think if not those who are different from ourselves?» (Postmodernism, Humanism and Diversity). This striking view suggests that our identity ("we") is only meaningful in relation to other identities – selfhood and community are co-created through difference. In practical terms, this means that a truly humanistic society must not only embrace but also protect diversity (of cultures, viewpoints, and persons) as an end in itself.

Philosophers such as Emmanuel Levinas have also argued that ethical responsibility arises in the encounter with the Other – the face of someone different who calls us to respond. Diversity thus becomes the ground of ethics: it reminds us that no single perspective is absolute and that empathy and respect are needed to bridge the gap between self and other. Modern humanist ethics has increasingly embraced this idea. It posits the «inherent worth of every person» and seeks a “world community” where differences are accepted and dialogued with, not erased (Postmodernism, Humanism and Diversity). In sum, philosophical perspectives (especially in the last few decades) frame human diversity not as an obstable to be overcome, but as the very context that makes understanding, conversation, and moral progress possible. Difference is seen as fundamental to how we define ourselves and relate to each other.

History provides many examples of how diversity has been an engine of human progress and a source of resilience in difficult times. Far from holding societies back, the exchange of diverse peoples and ideas has often catalyzed leaps in innovation and understanding. In fact, historians note that cross-cultural interactions have influenced the development of nearly all societies throughout history (19 Cultural Exchanges in World History). Sociologically, diverse communities and teams can draw on a wider range of experiences and skills, making them better equipped to solve complex problems and adapt to change.

From ancient history to the present, diversity has been a source of strength for humanity. It has fostered the cross-fertilization of ideas, driven socio-economic development and provided a buffer against threats. Societies that have welcomed a plurality of people and viewpoints, while not without challenges, have often been more dynamic, creative, and resilient than those that have enforced uniformity. The historical and sociological record is thus consistent with the biological, anthropological, and ethical perspectives: diversity is deeply woven into the fabric of human success.

Work by Eduardo Kobra, Wynwood Exhibition, Miami, Florida, USA. Photo by jpeligen.

Conclusion

Across scientific and humanistic disciplines, a common theme emerges: human diversity is fundamental to who we are and how we survive and thrive. Evolutionary biology shows that our species could not have adapted to different environments and survived disease without genetic diversity. Cultural anthropology shows that the dizzying array of human cultures is precisely what enabled our ancestors to innovate and inhabit every corner of the globe. Philosophical and ethical considerations suggest that engaging with human differences is essential for understanding ourselves, for moral growth, and for a conflict-ridden but war-free global society. History and sociology offer concrete examples of the rewards of diversity in fostering progress, creativity, art, and resilience. Diversity is not just a nice feature of humanity, but part of its foundation, an evolutionary and civilizational imperative that continues to shape our destiny. Embracing, preserving, and defending this diversity (biological, cultural, intellectual) is likely to remain critical to our future challenges, ensuring that we have the breadth of ideas and skills needed to thrive in a too fast-changing, complex world.

Mural do Coexistência by Brazilian street artist Eduardo Kobra, Pinheiros district, São Paulo, Brazil.

Bibliography

Doug Brugge, PhD, MS, and Rob Goble, PhD, The History of Uranium Mining and the Navajo People, in "American Journal of Public Health", September 2002, Vol 92, No. 9

The Center for Public Integrity is a nonprofit newsroom investigating inequity and holding powerful interests accountable. See the article Nuclear buildup sickened his community. Then it caught up with him, by Yvette Cabrera, November 30, 2022.

Geoffrey H. Fettus and Matthew G. McKinzie, Environmental Damage and Public Health Risks From Uranium Mining in the American West, Natural Resources Defense Council, March 2012

Härting FH, Hesse W. Der Lungenkrebs, die Bergkrankheit in den Schneeberger Gruben in "Vierteljahrsschrift für gerichtliche Medicin und öffentliches Sanitätswesen", 1879.

Abandoned Mines Cleanup, March 14, 2025, by US Environmental Protection Agency.

Tribal Members Journey to Washington Push for Reauthorization of Radiation Exposure Compensation Act, by Noel Lyn Smith, in "Inside Climate News", September 27, 2024.

‘Ignored for 70 years’: human rights group to investigate uranium contamination on Navajo Nation, by Cody Nelson, in "The Guardian", October 27, 2021.

One World (We Are One) by IllumiNative and Mag 7

"We can find unity in our diversity. I am proud to partner IllumiNative and Mag 7 for the release of “We Are One,” a collaboration to show the richness, diversity, and beauty of Indian Country. Today on Indigenous Peoples' Day and every day we are here to say that We Are Still Here. Research has shown that the lack of representation of Native peoples in mainstream society creates a void that limits the understanding and knowledge that Americans have of Native communities. We are here to fight the invisibility that Natives face by amplifying contemporary, authentic Native voices, and supporting Native peoples tell their story. We as humans all live in this one world where we have to work and live together. Our goal is for Native peoples to be normalized in a current today and show accurate and positive representations of our people. About IllumiNative and Mag 7: IllumiNative is an initiative, created and led by Natives, to challenge the negative narrative that surrounds Native communities and ensure accurate and authentic portrayals of Native communities are present in pop culture and media."

Mag 7 is a collective of seven MCs and songwriters from different tribes, who came together for hope and optimism. The members of Mag 7 are Drezus (Plains Cree tribe), Supaman (Crow tribe), PJ Vegas (Shoshone / Yaqui tribes), Kahara Hodges (Navajo tribe), Doc Native (Seminole tribe), Spencer Battiest (Seminole tribe), and Emcee One (Osage/Potawatomi tribes).

Alyx Becerra

OUR SERVICES

DO YOU NEED ANY HELP?

Did you inherit from your aunt a tribal mask, a stool, a vase, a rug, an ethnic item you don’t know what it is?

Did you find in a trunk an ethnic mysterious item you don’t even know how to describe?

Would you like to know if it’s worth something or is a worthless souvenir?

Would you like to know what it is exactly and if / how / where you might sell it?