NAVAJO CHURRO SHEEP AND WOOL 4

USA on the globe.

Licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported.

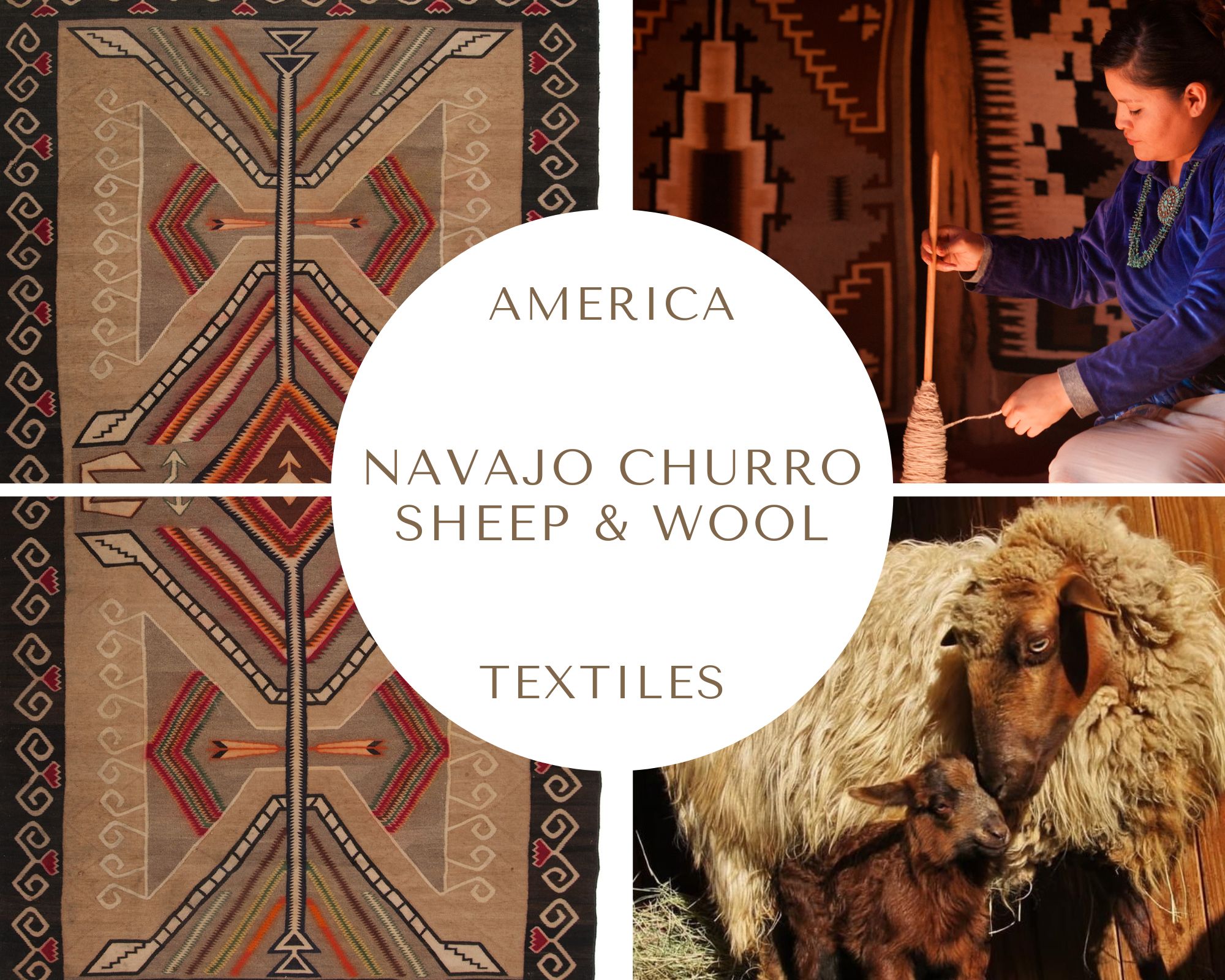

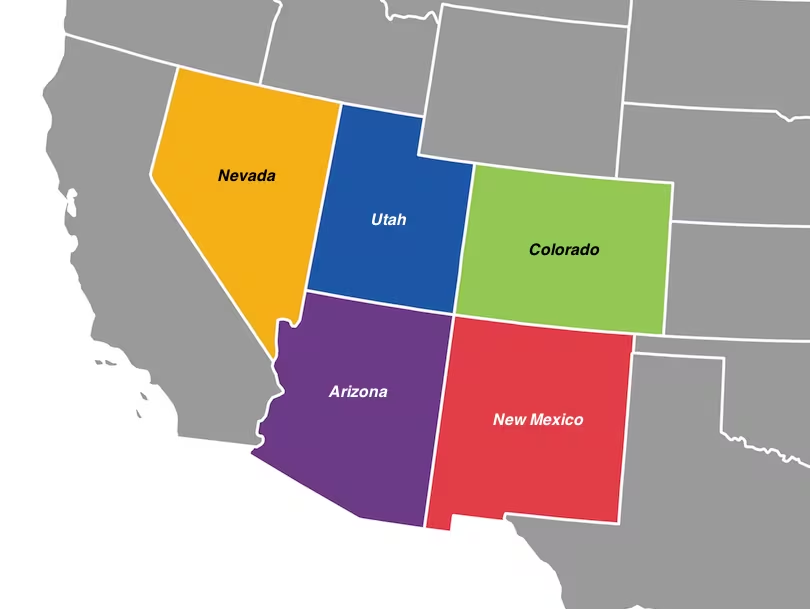

SOUTHWESTERN STATES

TRADITIONAL WOOL AND WEAVING PRACTICES

The genetic and cultural imprint of the Navajo Churro sheep on Navajo weaving is inseparable, shaping one of North America's most revered artistic traditions. From the wool's unique physical properties to its sacred role in Diné cosmology, these sheep provided the raw material for textiles that transcended mere utility to become expressions of identity, spirituality, creativity, and resilience.

-

The Unique Characteristics of Navajo Churro Wool

Navajo Churro wool has several unique characteristics that have made it prized by textile artists, especially traditional Navajo weavers. These characteristics result from the breed's adaptation to the arid environment of the Southwest and centuries of selective breeding.

A double coat

The double coat of Navajo-Churro wool is one of its most distinctive and valuable characteristics, developed as an adaptation to the harsh Southwestern climate, providing both insulation and protection from the elements.

Navajo-Churro sheep have a classic double-coat structure consisting of two different types of fibers:

- Inner/Undercoat (Thel): It makes up about 80% of the fleece and measures 10-35 microns in diameter (mostly in the low 20s) with a length of 3-5 cm (7.5-12.5 cm). This component is fine to medium in texture and provides the wool's softness, warmth, and insulating properties of wool.

- Outer Coat (Tog): Comprises about 10-20% of the fleece and measures over 35 microns in diameter (mostly 50-60 microns) with a length of 15-30 cm. This longer, coarser component extends beyond the undercoat and contributes significantly to durability and wear resistance.

- Kemp: A third minor component (less than 5% of the fleece) consisting of very coarse, opaque fibers measuring 65+ microns. While present in small amounts, excessive kemp is considered undesirable in registered animals.

This double-coated structure creates a distinctive lock formation and provides several key benefits:

- The undercoat provides cushioning, insulation, and bulk, while the outer coat adds strength and durability to textiles.

- Wool is particularly suited to traditional spinning and weaving techniques. The fiber combines strength and bounce in exceptional ways.

- This dual nature allows fiber artists to approach wool in a variety of ways, either using both coats together or separating them for different applications.

This distinctive double-coat structure is central to what makes Navajo Churro wool prized by traditional Navajo weavers and contemporary fiber artists alike, offering a unique combination of qualities not found in other sheep breeds. The Navajo Churro fiber also resists pilling over time, contributing to the longevity of finished pieces.

Low Lanolin for Water Conservation

Raised in their natural desert environment, the wool is remarkably low in lanolin, making it less greasy than many other breeds.

The Navajo Churro's double-coated fleece contains less than 3% lanolin-a fraction of the 15-25% found in breeds such as Merino. This critical characteristic eliminated the need for water-intensive scouring in the arid Southwest, where springs yielded only 10-20 gallons (38-76 liters) per household per day. Weavers could shear, hand clean, and spin wool directly, conserving scarce water for drinking and livestock. Comparative studies show that Churro wool requires 75% less water than European breeds, a life-saving efficiency during droughts. In addition, the low fat content repels sand and dust, another remarkable advantage in the desert.

Structural Advantages for Weaving

The fiber has a high luster that enhances the appearance of finished textiles. Under a microscope, Churro fibers exhibit translucent, tightly coiled cortical cells that refract light, creating the characteristic luster of classic Navajo textiles. The long staple outer layer provided tensile strength, while the soft inner layer allowed dense packing without brittleness. When spun, these two layers produced yarn with 40% more twist retention than commercial wool, allowing intricate geometric patterns without warp distortion.

Navajo Churro sheep

Photo Courtesy of (clockwise): Brown Sheep Farm; Melanie Stetson Freeman/The Christian Science Monitor; Sagebrush Valley Ranch, Arizona; Puddleduck Farm, Oregon; Tanya Charter Pearl.

Natural Palette and Dye Absorption

Navajo-Churro sheep have an impressive range of natural colors, making them especially valuable for creating naturally colored textiles. Their color palette ranges from whites to browns (beige to chocolate) and blacks (light gray to night black). Common colors include white, cream, tan, brown, gray, black, and even red brown. This natural color variety helps weavers create intricate designs without requiring dyes for each color element.

Pre-colonial weavers used the race's wide natural color spectrum to create banded "chief's blankets" without the use of synthetic dyes.

The introduction of indigo and cochineal dyes represents a significant chapter in the evolution of Navajo weaving, dramatically expanding their color palette and influencing their textile traditions.

Indigo blue was introduced to the Navajo by the Spanish during the early colonial period, likely in the mid-1700s. Historical evidence indicates that:

- Indigo dye was obtained through trade routes and purchased in lumps;

- It became one of the three primary colors (alongside natural brown and white) in Navajo weaving prior to the mid-19th century;

- The Navajo developed sophisticated techniques with indigo, creating shades ranging from pale blue to near black;

- They mixed indigo with indigenous yellow dyes like rabbit brush (Ericameria nauseosa) to achieve bright green effects, further expanding their palette.

Cochineal, which produces brilliant reds, had a more complex introduction to Navajo weaving.

- Initially, cochineal entered Navajo textiles indirectly through "bayeta," a cochineal-dyed trade cloth from England, Spain, and Mexico.

- Rather than dyeing with cochineal directly, Navajo weavers would unravel these imported textiles and reweave the colored yarn into their blankets.

- This practice was established by the early 19th century, as "there are few examples of Navajo weaving between 1804 and 1850, but the last 30 years of this period are well represented".

- Bayeta was occasionally used in first-phase Navajo chief's blankets, but became prominent in second-phase blankets (mid-19th century).

The direct use of cochineal by Navajo weavers to dye their handspun wool (rather than just reusing unraveled bayeta) appears to be a later development and was less common due to expense. Archaeological research has identified instances of Navajo handspun yarn dyed with cochineal, challenging earlier assumptions about Navajo dyeing practices.

These dyes transformed Navajo textile art in several significant ways.

- Red from cochineal was highly prized because there's no plant in the Southwest that will give such an intense red.

- By the mid-19th century, these dyes had helped expand the Navajo color palette to include red, black, green, yellow.

- The introduction of these colors coincided with evolving design elements, as weavers moved from simple alternating stripes to more complex patterns incorporating diamonds, triangles, and zigzag lines.

- The use of these dyes helped establish distinctive Navajo weaving traditions that set them apart from other textile traditions.

Before 1868, the Navajos primarily used "natural fleece colored yarns supplemented with a limited number of dyed yarns" including indigo blue, yellow from plant sources, and green from over-dyeing techniques. The introduction of aniline dyes in the late 19th century (1880s) dramatically changed Navajo weaving, as these synthetic dyes offered bright shades of red, orange, green, purple, and yellow that were previously difficult to achieve with natural materials

Interestingly, the extensive use of diverse local plant dyes was not part of the original Navajo tradition but emerged later: The "revival" of vegetal dyeing began in the 1920s in Chinle with Cozy McSparren; Don Jenson continued this work in the 1940s; Bill and Sally Lippincott, owners of the Wide Ruins Trading Post, encouraged weavers to use vegetal and native dyes in the 1930s. In 1930, the Navajo tribe, the U.S. Government, and Anglo traders launched the "Chinle Vegetal Revival" project to expand vegetal dye use. It was during this revival period that Mable Burnside-Myers created her influential Navajo Dye Chart in the 1950s, documenting numerous plant sources including red onion skin, sunflower, alder bark, sagebrush, juniper bark, and rose hips. However, some sources suggest that the term "revival" is a misnomer since "vegetal dyes were never popular or extensively used by the Navajos" prior to this period.

LEFT: Undyed, natural color palette of Navajo Churro yarns by Tierra Wools, Chama, New Mexico, USA.

RIGHT: Navajo Churro yarns hand dyed with natural dyes from plants by Toni Boyd Broaddus. By Tierra Wools.

BELOW: Navajo Churro yarns hand dyed over wood fires by Tierra Wools master dyers.

-

Spider Woman’s Divine Instructions

According to Navajo mythology, Spider Woman plays a central role in teaching the sacred art of weaving to the Navajo people. The story of how this divine knowledge was transmitted is rich in symbolism and reflects the spiritual importance of weaving in Navajo culture.

Diné origin stories credit the deity Na'ashjé'ii Asdzą́ą́ (Spider Woman) with teaching weaving using materials that symbolize cosmic order:

- Warp: Celestial cords of sunlight

- Weft: Cotton struck by lightning

- Wool: Crystal-infused Churro fleece

This sacred narrative positioned sheep husbandry and weaving as reciprocal acts of reverence. As artist Barbara Ornelas notes: The loom is our altar, the wool our prayer.

The Holy Ones provided the Spider Man with specific instructions for creating the sacred loom and teaching its construction to the Diné. The process incorporated cosmic elements that reflected the sacred nature of weaving: the crosspieces were made of sky and earth cords, the warps of sun rays, the healds of rock crystal and sheet lightning. The batten was a sun halo, and the comb was made of white shell.

For the spindles, four different tools were created, each with sacred components:

- One a zigzag lightning rod with a whorl of cannel coal;

- One a lightning rod with a whorl of turquoise;

- A third had a sheet lightning rod with a whorl of abalone;

- A rain streamer formed the rod of the fourth, and its whorl was white shell.

The Sacred Journey to the Four Mountains

A central aspect of Spider Woman's divine teaching involved gathering materials from the four sacred mountains of the Navajo world:

- Blanca Peak (Sisnaajiní) - the sacred mountain of the East: Here she obtained wood for Spider Man to make the loom.

- Mount Taylor (Tsoodził) - the sacred mountain of the South: From this mountain, she harvested plants to make plant dyes for dyeing wool.

- San Francisco Peak (Dook'o'oosłííd) - the sacred mountain of the West: Here she received designs from the Thunder Gods, who gave her permission to use them in her weaving and instructed her to teach them to future weavers.

- Mount Hesperus (Dibé Nitsaa) - the sacred mountain of the North: From this last mountain she received the sacred prayers and songs associated with each stage of weaving.

The Four Sacred Mountains of the Navajo/Diné People

The Four Sacred Mountains (Dził Diyinii Dį́į'go Sinil in Diné bizaad) form the spiritual boundary of the Navajo traditional homeland and represent the cardinal directions in Navajo cosmology. Sisnaajiní (Blanca Peak, Colorado) in the east is associated with the color white and represents dawn and sunrise. Tsoodził (Mount Taylor, New Mexico) in the south is associated with the color blue, representing the midday sky. It's also called "Turquoise Mountain". Dook'o'oosłííd (San Francisco Peaks, Arizona) in the west is associated with the color yellow, representing sunset and evening light. It is known as "the peak that never melts" or "the abalone shell mountain". Dibé Nitsaa (Hesperus Mountain, Colorado) in the north is associated with the color black, representing darkness. Also called "Great Sheep".

According to the Diné Bahaneʼ (the Navajo creation story), the Creator placed the Diné home among these four mountains. The Navajo consider them to be deities that provide essential resources for their livelihood, possess supernatural power, and were among the first places created in this world where the sacred people are most accessible to mortal pilgrims. The mountains are integral to Navajo prayers, chants, and ceremonies, including the Blessingway (considered the backbone of Navajo religion), the Beautyway, and the Mountainway. Navajo people visit these sacred sites to gather plants and soil for ceremonies and to connect with spiritual forces. The Four Sacred Mountains embody the essence of life and cosmic harmony. They represent orderly and proper conditions of balance, with day and night, male and female, and other complementary states as interdependent parts of a whole system.

The Four Sacred Mountains appear on the seal and flag of the Navajo Nation. The latter is shown at the bottom of the map above, while the seal is shown below. Officially adopted on January 18, 1952, it contains several significant elements that represent Navajo heritage, sovereignty and values: the four sacred mountains; the livestock - a horse, a cow and, of course, a Navajo churro sheep; two green corn plants symbolizing the sustainer of Navajo life. The seal is surrounded by 50 arrowheads (originally 48 when first created) representing the protection of the Navajo Nation in all states of the United States. The three concentric circles with an opening at the top represent a rainbow and the sovereignty of the Navajo Nation.

Transmission of Knowledge to the Navajo

Spider Woman's divine knowledge was meant to be shared. According to some accounts, she taught Changing Woman how to weave with the understanding that this knowledge would be passed on to the Navajo people. In other versions, Spider Woman directly instructed Navajo women in the art of weaving using the loom that Spider Man had helped them make.

The ceremonial aspects of weaving were also taught, including songs that "strengthen the weaving and the weaving tools. Spider Woman advised that spider webs be rubbed on the palms of young girls to make them good weavers, a practice that continues in some traditional communities.

In Navajo culture, weaving is more than a craft-it is prayer in motion. The story of Spider Woman emphasizes that "weaving is not an act of creating something - it is an act of uncovering a pattern that was already there. This reflects the spiritual understanding that the weaver connects to cosmic patterns and divine order through her work.

The continued honoring of Spider Woman in traditional weaving practices – such as the inclusion of a "spirit outlet" or Spider Woman's cross in Navajo textiles – testifies to the enduring spiritual significance of this divine instruction that has shaped the Navajo cultural heritage for generations.

Two Navajo/Diné baskets.

LEFT: A large coiled tray with three spider woman crosses in red and black, second half of the 20th century. Sold at auction in 2022 by John Moran Auctioneers, CA, USA.

RIGHT: Spider Woman Crosses, 1996, by Peggy Black. Photo by Kirstin Roper, © Natural History Museum of Utah, USA.

Na'ashjé'íí Asdzą́ą́ (Spider Woman) is often represented and honored with a cross symbol. This motif was common in early rug designs and continues to appear in rugs and baskets still today. Although the design and placement of the cross may vary, you'll never find it in a diamond or square because such a pattern would trap her divine spirit.

Navajo Spider Woman contemporary ceremonial basket by Fannie King. Video from Twin Rocks Trading Post, Utah, USA.

Navajo Spider Woman Cross Rug by Ofelia Joe. Video from Twin Rocks Trading Post, Utah, USA.

-

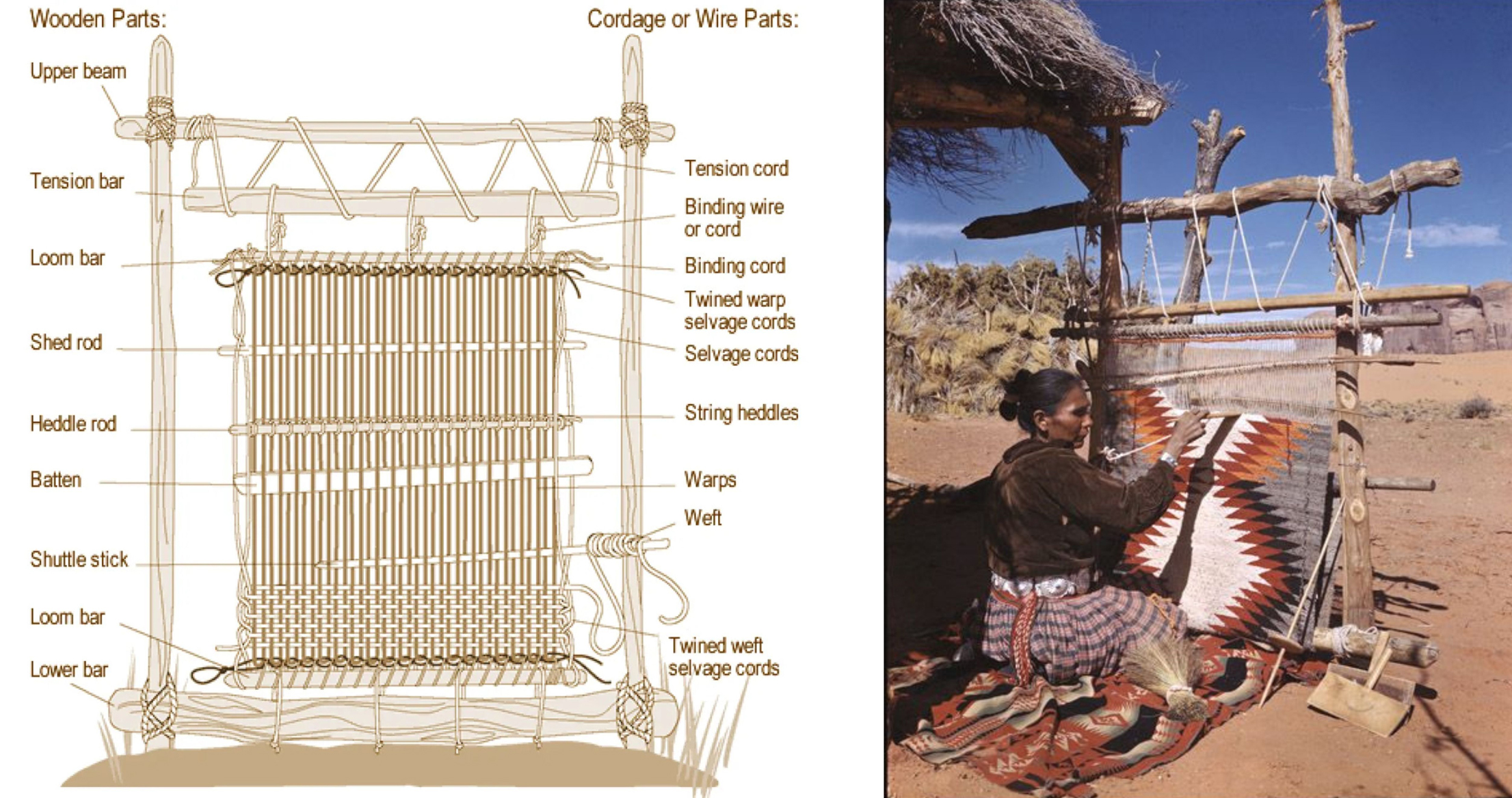

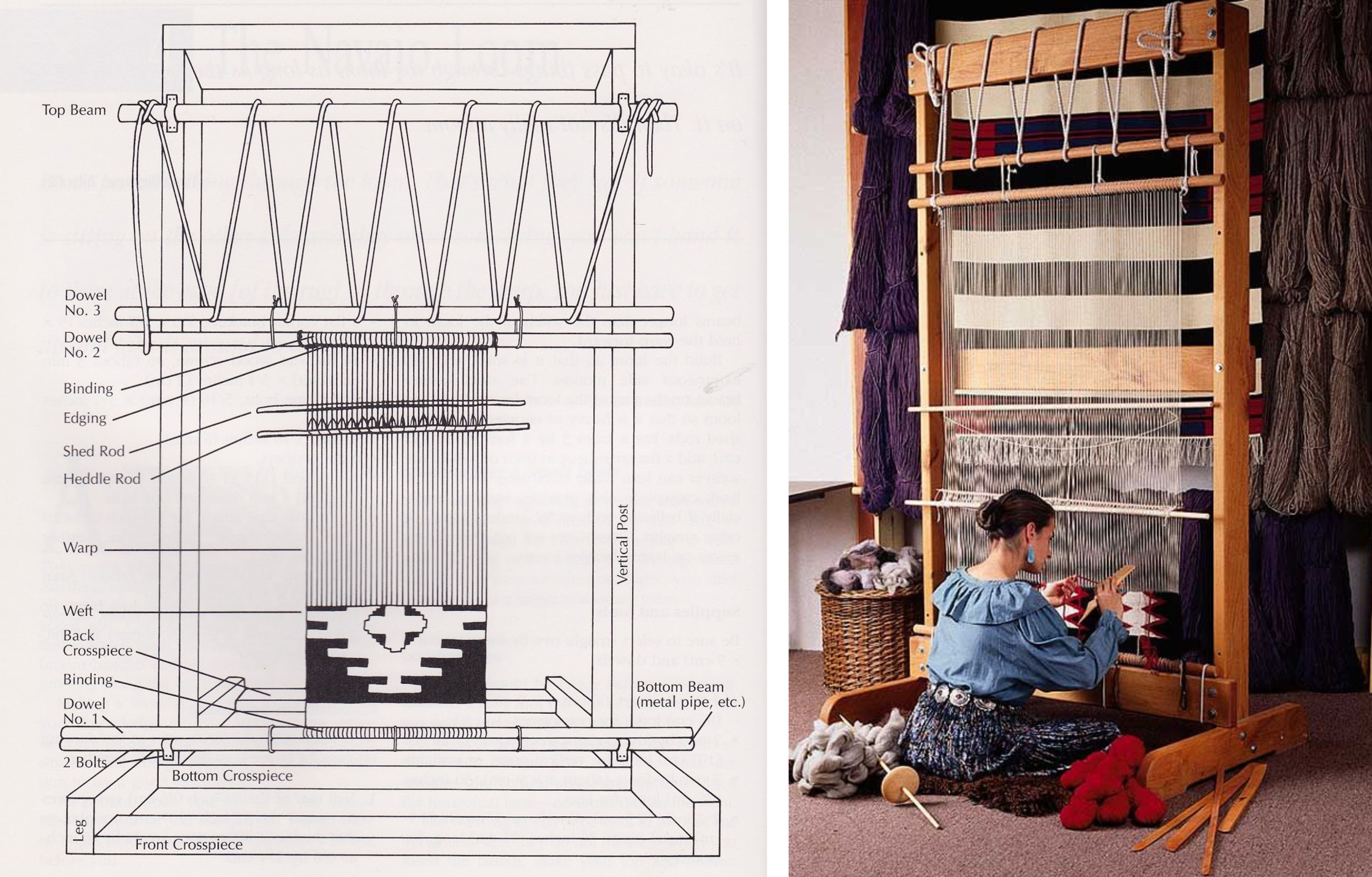

Traditional Navajo/Diné Loom

The traditional Navajo loom is a masterpiece of functional design that has remained remarkably consistent through centuries of use. Its structure and components reflect both practical needs and cultural significance within the Diné weaving tradition.

The traditional Navajo loom, presumably acquired from the Puebloans of the Colorado Plateau, is a freestanding, upright frame with a simple yet effective design. It consists of a four-sided frame with no moving parts that traditionally sits on the ground. This vertical orientation is fundamental to the tapestry technique used in Navajo weaving, where the warp threads are placed vertically on the wooden frame and then the horizontal weft threads are woven through them.

The frame is made of wooden posts and top and bottom crossbars to hold the warp, and is traditionally constructed of heavy logs suspended from trees or a wooden frame. Modern versions sometimes substitute steel tubing for wood while maintaining the traditional design. Feet on either side of the base provide stability for the loom during weaving.

Vertical threads (warp) are tied to the frame and provide the structure for the weave. The warp threads must be carefully tensioned for successful weaving.

The sheds (the openings between the separated warp threads) are operated manually. For more complex weaves, such as twill or two-ply, there may be one stick shed and several draw sheds.

The traditional tensioning system consisted of a rope for tensioning the warp. Today, many weavers use turnbuckles to achieve a more even tension. Older weavers, especially in places like Canyon de Chelly, may still use the traditional rope method with a loom tied to a beam on the ground and tensioned by ropes on upper beams tied to a tree limb above.

Wooden slats and rods at the bottom of the loom act as guides for the weaving pattern. These open the warp threads to guide the weaver in creating patterns.

Essential Tools Used with the Loom

- Battens are slender, flat, tapered pieces of wood used to keep the warp sets apart during the weaving process. They range from ½ inch to 1 inch wide, with the length matching the width of the loom. As weaving progresses, thinner battens are needed, so weavers typically have three different widths.

- The combs are used to knock each weft yarn firmly into place after weaving through the warp; they come in various shapes and sizes and are made of different types of wood. The number of teeth in the comb affects the tightness of the weave.

- The needles are used to weave the weft through the warp threads.

The design of the Navajo loom is particularly suited to a nomadic lifestyle. The entire project can be disassembled and rolled up for travel, then reassembled for weaving later. The loom itself can be disassembled and bundled into a smaller mass for transportation.

A key feature of Navajo weaving is that it produces a four-selvage weave with no fringe on the finished product or extra warp extending beyond the project that would need to be tied or knotted.

Traditional weaving on this loom requires patience, discipline, and considerable skill, especially in maintaining even tension throughout the piece.

Above: The old traditional Pueblo-Navajo upright loom. Illustration by Kathleen Koopman. From "Blanket Weaving in the Southwest" by Joe Ben Wheat, edited by Ann Lane Hedlund, 2003, The University of Arizona Press.

Below: The modern version of the traditional Navajo loom (Drawing: from Don Dedera's book Navajo Rugs).

The left vertical beam is associated with the female aspect while the right one with the male. The upper beam is associated with father sky, while the lower bar with mother earth.

Connor Chee - Weaving (from Scenes from Dinétah) | Navajo Piano.

Connor Chee (b. 1987) is a Diné (Navajo) composer and pianist known for blending Western classical music with the rich cultural heritage of the Navajo people. Chee made his Carnegie Hall debut at the age of 12 after winning a gold medal in the World Piano Competition and is a graduate of both the Eastman School of Music and the University of Cincinnati’s College-Conservatory of Music.

Alyx Becerra

OUR SERVICES

DO YOU NEED ANY HELP?

Did you inherit from your aunt a tribal mask, a stool, a vase, a rug, an ethnic item you don’t know what it is?

Did you find in a trunk an ethnic mysterious item you don’t even know how to describe?

Would you like to know if it’s worth something or is a worthless souvenir?

Would you like to know what it is exactly and if / how / where you might sell it?