NAVAJO CHURRO SHEEP AND WOOL 3

USA on the globe.

Licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported.

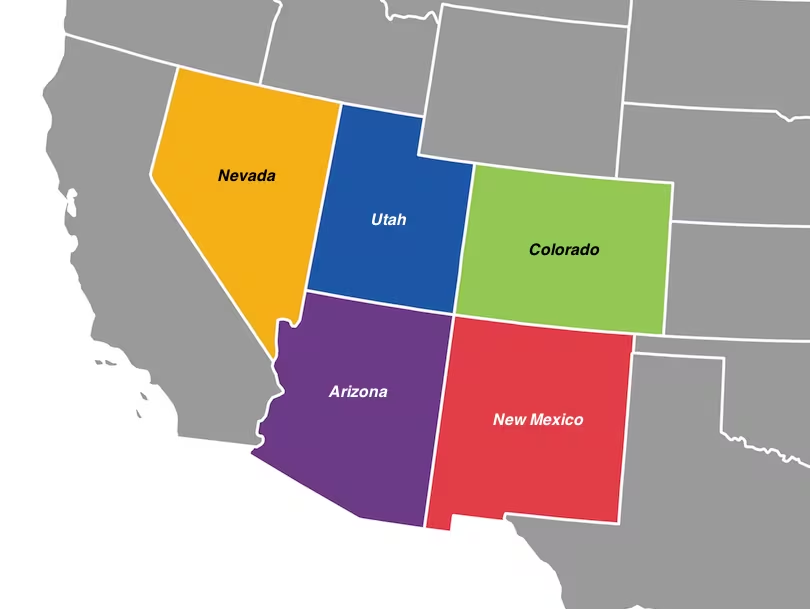

SOUTHWESTERN STATES

HOW THE STORY OF THE NAVAJO CHURRO SHEEP BECAME INTERTWINED WITH THE HISTORY OF THE NAVAJO NATION

Prior to Spanish colonization, the Navajo relied on hunting, gathering, raiding, and limited agriculture. The introduction of Churra sheep, horses, and goats by the Spanish in the late 17th century allowed for a shift to herding, which became the cornerstone of the Navajo economy: they slowly transitioned to a pastoral and agricultural society capable of utilizing the natural resources around them.

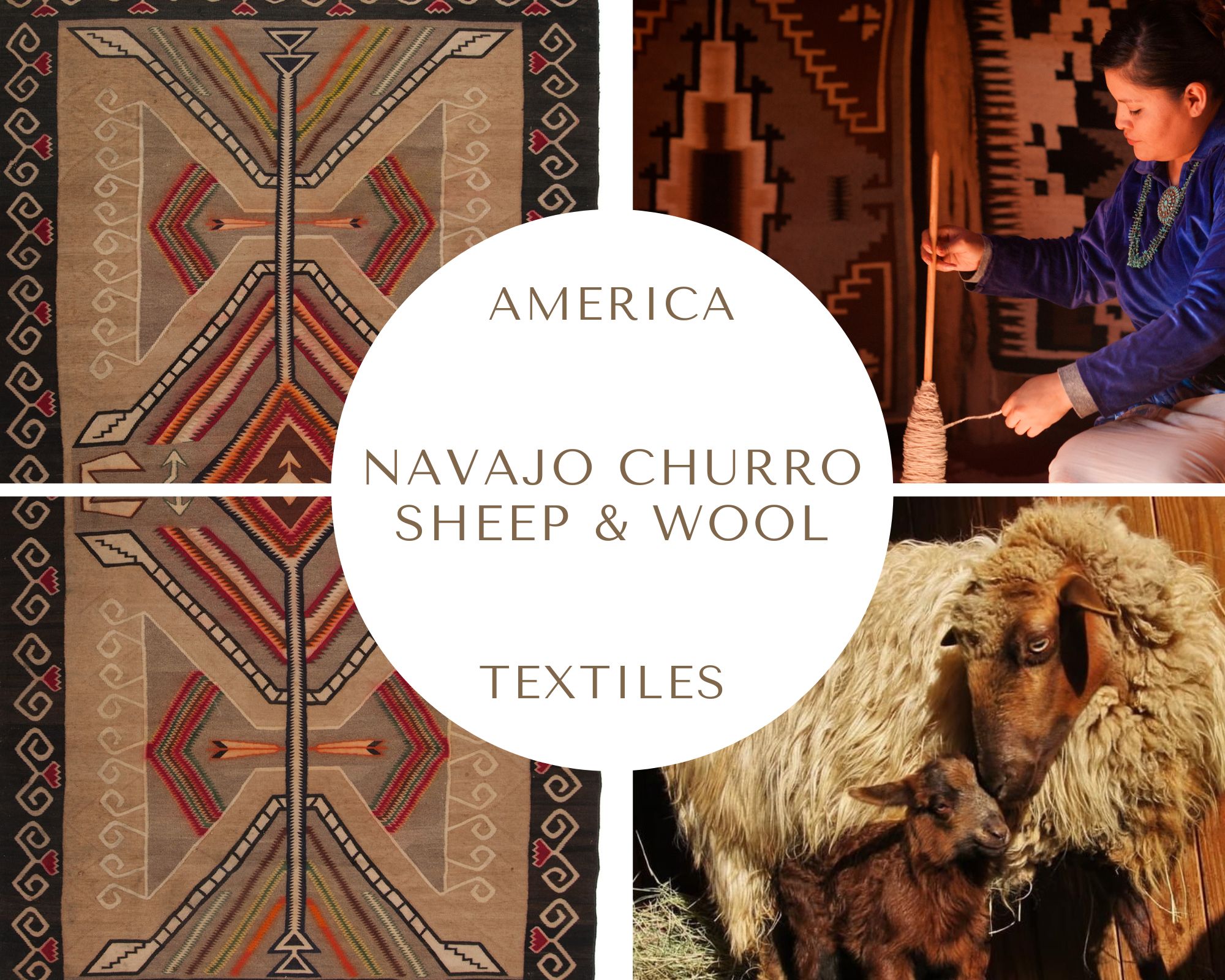

By the mid-18th century, Navajo herds numbered in the tens of thousands, with sheep serving as a mobile "bank" that could be expanded through breeding or traded in times of crisis. The breed's hardiness allowed herds to thrive on the arid Colorado Plateau, requiring minimal water and feeding on native forage such as sagebrush-a critical advantage in a region where crop failures were common. According to Charles Avery Amsden, Navaho weaving began in the early 18th century. Within a century, herding and weaving became major economic assets for the Diné. "It was from churro wool that the early Rio Grande, Pueblo, and Navajo textiles were woven - a fleece admired by collectors for its luster, silky hand, variety of natural colors, and durability." (Navajo-Churro Sheep Association).

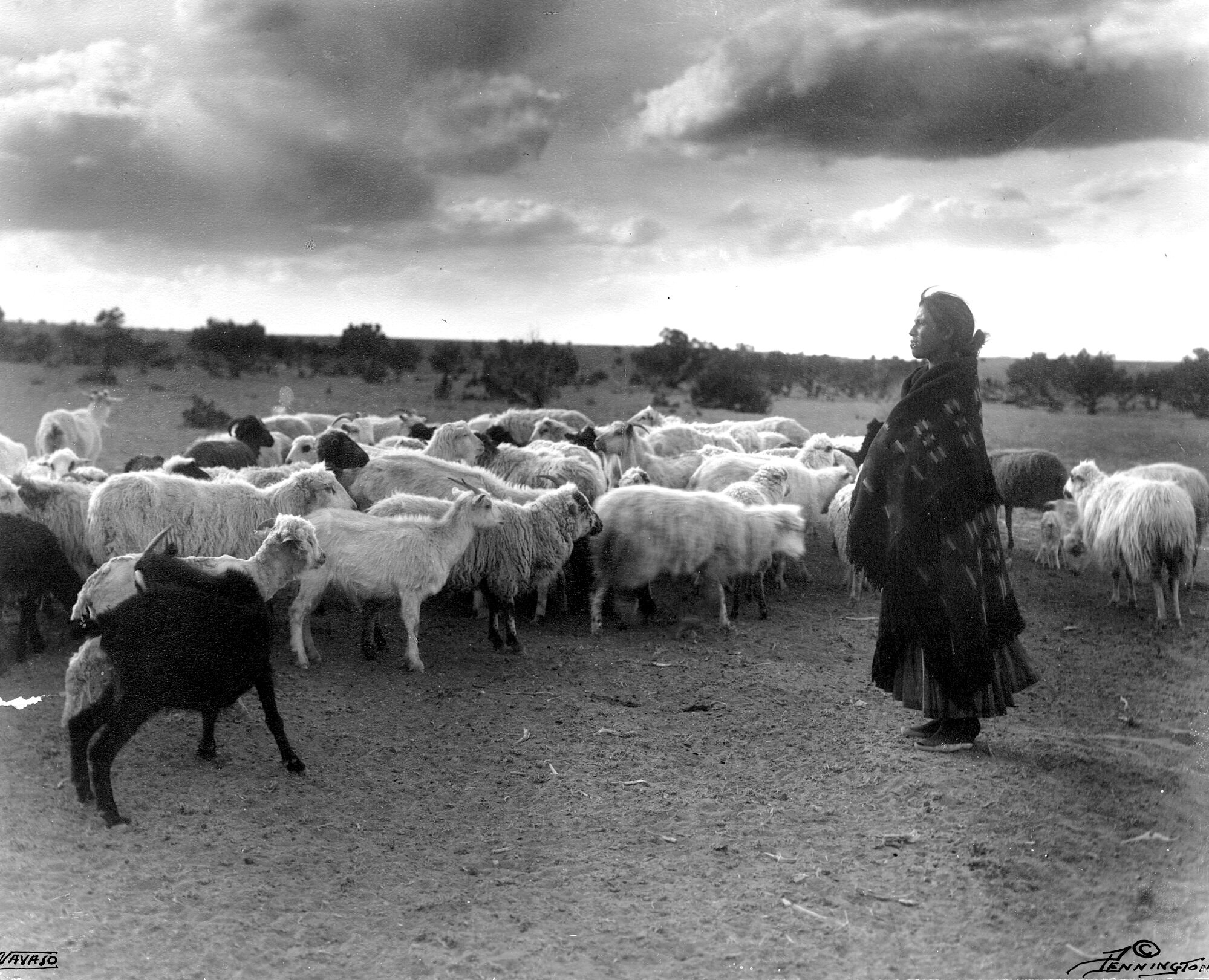

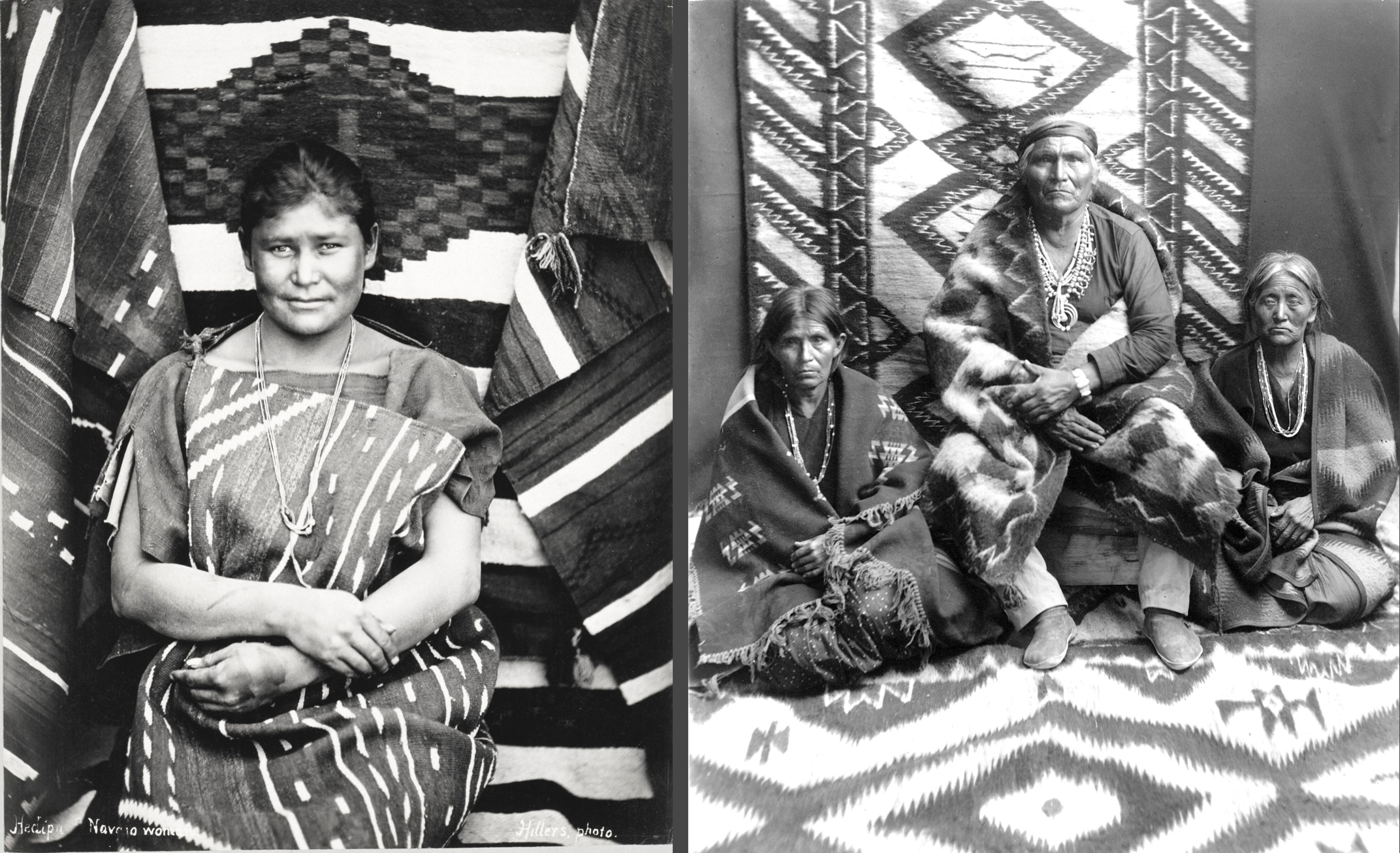

Navajo women woven rugs, carpets, blankets, saddle covers, coats, and clothing textiles so valuable that they eventually became prized commodities throughout the Southwest, contributing greatly to the wealth of Navajo communities. Navajo Churro wool was highly sought after by all trading partners because of its many natural colors. These sheep have a thick, double-coated fleece (coarse topcoat and fine bottomcoat) that comes in a range of natural colors: off-white, creamy white, beige, light tan, gray, blue-gray, brown, red-brown, and black. The introduction of indigo dye by the Spanish settlers and its adoption by the Navajo increased the demand for Navajo weavings. Flock ownership became a symbol of material wealth, and the Navajo churro sheep became an integral part of Navajo pastoral society and cultural identity.

By the first half of the 19th century, a wealthy Navajo household might own 50-100 sheep, with regional leaders maintaining flocks of over 1,000 head and fostering a decentralized trading network throughout the Southwest.

Women, who managed the flocks and weaving, held considerable economic power; larger flocks meant greater wool production, allowing families to trade surplus textiles for metal tools, cloth, and food staples. Thus, sheep provided not only subsistence-they were a source of milk, meat, and wool-but also a durable economic framework that sustained the Diné through colonial disruption, federal oppression, and environmental challenges. Unfortunately, the Navajo Churro sheep also became an integral part of the Navajo Nation's painful history.

The breed came close to extinction twice: once in the 1860s when the U.S. Army decimated Navajo herds, and again in the 1930s during a government-imposed livestock reduction. It also faced a serious threat during the radioactive contamination of Navajo Nation land in the mid-20th century.

The first near-annihilation of Diné people and their sheep

The first near extermination of the race occurred during the U.S. government's campaign against the Navajo in 1863-1868. Colonel Christopher "Kit" Carson, assigned by Brigadier General James H. Carleton to suppress tribal resistance, implemented a scorched-earth policy: his troops destroyed crops and peach orchards, burned homes, killed horses, poisoned wells, and slaughtered thousands of Navajo Churro sheep. This devastating campaign was designed to starve the Navajo into surrender and force them to give up their ancestral homelands to make way for white settlers and miners.

As we've seen, after Carson's campaign, the Navajo people were forced to march from their homelands to the Bosque Redondo internment camp in eastern New Mexico. This forced relocation, known as "The Long Walk," was called "Hwéeldi" or "Place of Suffering" by the Diné, and the campaign had a devastating effect on the Navajo Churro sheep population:

- Before the campaign, there were millions of Navajo Churro sheep in the Four Corners region.

- Navajo families who surrendered were allowed to take their remaining livestock with them.

- The sheep population dwindled dramatically during the internment period, from 6,962 to just 940 in 1868.

- Starvation forced the Navajo to slaughter the animals for meat, even though they needed their wool and milk.

Some Navajos escaped capture and hid with their sheep in remote canyons in New Mexico and Arizona, preserving small flocks of sheep. After three years, the Navajo survivors were allowed to return to a portion of their ancestral lands under the Treaty of Bosque Redondo and were given two "Indian" sheep per person from Hispanic flocks.

The recovery of the Navajo-Churro sheep population was slow and faced additional challenges, but was ultimately successful due to the skill of the Navajo shepherds.

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, livestock once again became the primary form of economic prosperity for the Diné. The average Navajo family owned 100 horses, 300 sheep, and 100 cattle. According to the Navajo-Churro Sheep Association, the total number of sheep on the Navajo Reservation reached over 574,821 head by 1930. The large number of animals led to overgrazing and soil erosion. This prompted the U.S. government to step in and make changes, and the Livestock Reduction Plan was implemented and enforced. (Indigenous Voices of the Colorado Plateau and Lawrence C. Kelly).

A Navajo woman stands near her herd of sheep in either Arizona or New Mexico. Photo by William M. Pennington, taken between 1904 and 1932. Source: Denver Digital Library, Special Collections, [call number X-33103], CO, USA.

Navajo weaver spinning wool into yarn; full-length, seated, with a loom behind her, Torreon, New Mexico, 1930s. Photo by Milton Snow. From the US National Archives, public domain.

Navajo children pose indoors. Both wear Navajo blankets and are seated on traditional carpets. Photo by William M. Pennington, taken between 1904 and 1932. Source: Denver Digital Library, Special Collections, [call number X-32998], CO, USA.

The second near-annihilation of Diné people and their sheep

Federal policies in the 1930s dealt a second blow. Citing overgrazing during the Dust Bowl, the Bureau of Indian Affairs mandated livestock reductions, targeting “unimproved” breeds such as the Navajo Churro. In addition, the large number of sheep, goats, horses and cattle owned by the Diné was considered problematic for the severe drought conditions of the early 1930s, so the U.S. government imposed and implemented a livestock reduction.

In 1933, some livestock was purchased for $1-1.50 (well below market value), but the reduction was so slow that approximately 30% of each household's sheep, goats, and horses were slaughtered by government agents and thrown into arroyos or burned (Navajo-Churro Sheep Association). This horrific culling is still vividly remembered by Navajos, whose relationship with animals is nothing like that of a modern dairy or meat company. Between 1933 and 1945, federal agents killed more than 400,000 Navajo sheep, often shooting them in front of the families who raised them. The same happened to horses. In one documented case, a family was told to bring their herd of 180 horses to a trading post, where the animals were slaughtered and the family received compensation for only 80 of them, and at below-market prices.

For the Diné, the U.S. government's 1933-1945 herd reduction was not only an economic disaster – it was an excruciating cultural and emotional trauma.

Federal herd reduction programs culled 85% of Navajo herds. At the same time, agricultural agencies encouraged crossbreeding with Rambouillet and Suffolk sheep to increase meat production, further diluting Churro genetics.

This cut the average family income in half, pushing 60% of Navajos below the poverty line. Hidden Churro flocks in remote canyons became lifelines, providing most of the wool used to weave Navajo textiles. By 1977, after radioactive contamination of land and water on the Navajo Nation, fewer than 500 purebred Navajo Churro survived, hidden in remote canyons by Diné elders who refused to comply with eradication orders.

Navajo Herder and Flocks, Arizona. Photo by Terry Eiler, 1930-33. Source: U.S. National Archives’ Local Identifier: 412-DA-1933.

A Navajo Rez puppy. Navajo livestock guardian dogs, often called "sheep dogs" or "rez dogs," differ from typical herding dogs in several important ways. Navajo dogs function primarily as guards rather than herders of sheep and goats. Unlike typical herding dogs used by other ranchers to help move herds, these dogs develop social bonds with the livestock they protect. Their primary job is to stay with the herd and defend it from predators, especially coyotes. Navajo Rez dogs are said to be able to cope with sub-zero temperatures in winter and the dry, hot summer temperatures typical of the Colorado Plateau. Photo by Donovan Shortey, Flickr.

The contemporary resurgence

The breed's recovery began in 1977, when Utah State University geneticist Dr. Lyle McNeal worked with Diné elders to locate remaining flocks. Organizations such as the Navajo-Churro Sheep Association and the Slow Food Presidium now coordinate breeding programs, combining genetic data with traditional ecological knowledge. Roy Kady, a founding member, emphasizes two goals: «We are not only restoring the sheep, but also our connection to the land and our ancestors.»

A number of grassroots organizations joined forces to revive the Navajo spinning and weaving traditions associated with the Navajo Churro breed, and to create a market for the Diné unique textiles. By 2005, the Navajo-Churro Sheep Association had registered more than 5,000 Navajo Churro heads and by 2022, there were more than 8,000 sheep (Henry Gass). However, today's Navajo Churro on the Navajo Nation – which, by the way, are all pasture-fed, antibiotic-free, and parasite-free – are still listed as critical by The Livestock Conservancy.

A 2004 USDA study analyzed pedigree data from the Navajo-Churro Sheep Breeders Association to evaluate conservation strategies. Despite a global population of 5,000 registered sheep, researchers found moderate inbreeding (average coefficient of 3.7%) due to the breed's bottleneck in the 1970s. However, geographic dispersal across 42 U.S. states created subpopulations with distinct genetic profiles, providing a buffer against disease. Notably, herd size showed minimal correlation with inbreeding levels (r = -0.07), suggesting that decentralized breeding programs have successfully maintained diversity. (A. N. Maiwashe and H. D. Blackburn).

Sheep Herding with the Navajo Edgewater Clan, by Steven Foreman.

Some thoughts about this history

The Navajo-Churro’s history encapsulates the ecological and cultural violence of colonialism, yet its revival demonstrates indigenous resilience in reclaiming biocultural heritage. Genetic studies confirm that decentralized, community-led conservation can save endangered species, while ethnographic work documents the inextricable bond between the Diné and their sheep.

The economic role of the Navajo Churro sheep goes beyond livestock production; it represents a symbiotic relationship between culture and commerce. Historical data show that at peak herd sizes (prior to 1863), sheep-related activities contributed 80-90% of Navajo wealth. Modern revitalization efforts show that niche markets for traditional products can yield 15-20% higher profit margins than mainstream agriculture. As climate change exacerbates drought in the Southwest, the breed's low water requirements position it as a sustainable economic asset, proving that traditional ecological knowledge and the wisdom embedded in traditional ranching remain vital to 21st century resilience.

Irene Bennalley, a Diné shepherdess, says she learned Churro herding from her grandfather, who secretly preserved breeding stock during the 1930s reduction. Such narratives underscore how cultural memory, not just genetics, required preservation.

Irene Bennalley holds up a rug she made from the wool of the Navajo-Churro sheep she raises on her ranch, the BarQ RZ Ranch, on March 1, 2022, outside Toadlena, New Mexico, in the Navajo Nation. Photo by Melanie Stetson Freeman; courtesy of "The Christian Science Monitor", April 7, 2022.

The contemporary resurgence of the Navajo Churro sheep, though fragile, has the merit of reconnecting Navajo communities with ancestral practices. Today, Navajo Churro sheep embody Diné self-determination.

- Resistance to Assimilation: Rejection of industrialized agriculture in favor of traditional herding.

- Intergenerational wisdom: Weaving and herding preserve language, stories, and kinship ties.

- Environmental stewardship: Herding practices reflect Diné ecological ethics and counter extractive land use.

- Political symbolism: As Jaynie Parrish notes, sheep represent "sovereignty and a foundation for Diné provisioning".

For the Navajo Nation, a connection to the land is a connection to heritage and identity - connections that were lost when the U.S. government nearly exterminated the Navajo Churro sheep in the 19th and 20th centuries. This connection to the sheep is the connection to the land, which is the connection to the culture, which is the connection to the spirituality of the Diné people.

Today, Navajo Churro sheep are actually raised by both Navajo people within the Navajo Nation and non-Navajo ranchers throughout the Southwest. This cooperative conservation effort has been instrumental in bringing the breed back from the brink of extinction. Conservation of the Navajo Churro sheep has become a collaborative effort involving people from diverse backgrounds: «Navajo, Hispanic and Anglo shepherds and producers are all working hard, often together, to protect and continue the growth of this breed and to raise awareness of its endangerment, cultural significance and invaluable qualities as a sustainable breed.» (Heath Herring and Leney Breeden). Many artists and weavers, Navajo and non-Navajo, are now working to transform the special wool of the Navajo Churro sheep into masterpieces of eco-sustainable design. In this way, breeders, shepherds, producers, artists, weavers, members of conservation organizations and associations are meeting, getting to know each other, discussing and exchanging views, breaking down cultural and ideological barriers that have been erected around the traditions and knowledge of the Diné, and creating a cultural encounter that does not dilute the historical identity of the Navajo people, but preserves, enhances and develops the deep and respectful bond the Diné have formed with Mother Earth and her creatures.

100% Navajo Churro wool yarns in their 100% natural colors. Photo and yarns by Cedar Mesa Ranch LLC, Dolores, Colorado. All the fibers come from the sheep raised on the ranch owned and managed by Andrew and Kendra Schafer according to sustainable practices. Both are expert in Integrated Resource Management and Holistic Management for land and business.

Lawrence C. Kelly, The Navajo Indians and Federal Indian Policy, University of Arizona Press, 1974, Tucson, Arizona, USA.

Navajo Livestock Reduction: A National Disgrace, Navajo Community College, 1974.

C.A. Amsden, Navaho Weaving: Its Technic and History, 1934, The Fine Arts Press, Santa Ana, California, in cooperation with The Southwest Museum; reprinted by in 1949 by The University of New Mexico Press, Albuquerque, and in 1991 by Dover Edition.

Indigenous Voices of the Colorado Plateau, Cline Library, Special Collections and Archives Department 2005, Northern Arizona University

N. Maiwashe and H. D. Blackburn, Genetic diversity in and conservation strategy considerations for Navajo Churro sheep, in American Society of Animal Science, 2004, 82:2900–2905

Henry Gass, "Reviving Navajo identity, one sheep at a time" in "The Christian Science Monitor", April 7, 2022.

The Navajo-Churro Shepherds by Heath Herring and Leney Breeden, Stetson Stories.

Navajo Churro Sheep Association official website.

GUARDIAN OF THE NAVAJO SOUL

THE SACRED ROLE OF THE CHURRO SHEEP IN CULTURE AND SPIRITUALITY

The Navajo people's relationship with their sheep was and is profoundly different from that of the commercial livestock industry: these sheep held and still hold deep cultural and spiritual significance within the Navajo culture, representing far more than just an economic resource. The phrase Dibé éí Diné be' iiná át'é ("Sheep is Life") sums up this special relationship.

Black Mesa sheep. Source: Navajo Sheep Project.

«The Navajo-Churro may be considered a ‘local’ domesticated breed, a type of livestock that has adapted well to a regional climate and vegetation, has developed disease resistance, and can make the most efficient use of resources in marginal environments. Smaller than improved breeds, the Navajo-Churro eat less, have narrow bodies, long legs, and light bones that enable them to walk long distances to graze on arid land. Their faces, legs, and abdomens have little fleece to snag on desert plants. They are known for fecundity: ewes mature early, lamb easily, often produce twins and triplets, and fiercely protect their lambs.» (Susan M. Strawn).

The relationship between the Diné and their sheep is deeply rooted in spiritual beliefs and origin stories. According traditional Diné knowledge, they asked their Holy People to send them sheep that they could care for and that would provide them with a sustainable livelihood. This request was fulfilled when the sheep arrived, seen as an answer to their prayers.

In Diné creation stories, the gods came together to create sheep from sacred materials:

- Wild tobacco for their ears

- Precious stones for their eyes

- Willow branches broken into four sticks for their legs

The Wind beings then blew the first breath into them, and the gods sent the sheep to earth upon a rainbow trail. This origin story establishes the Diné as shepherds of these sacred animals since the beginning of time.

In Diné cosmology, the sheep became inseparable from cultural identity. Oral traditions describe the Churro as a sacred gift from the Holy People, embodying the fundamental principle of Hózhó, harmony and balance between humans and nature.

The Holy People scooped handfuls of different colored clouds to form the sheeps’ bodies. White day clouds were gathered into white sheep. Black, nighttime clouds were molded into black sheep. Storm clouds were used to create gray or "blue" sheep. Tan-colored sheep were made from the yellow clouds of twilight. The Rainbow People gathered dusk’s orange and red clouds to form the first brown sheep, the most beautiful and sought after of all. The Rainbow beings gave a part of their beauty to create this sheep and they told the other deities that the brown sheep will be a rare "blessing" to a herd, to test the humility of humankind.

The first sheep were then assembled with wild tobacco for their ears, precious stones as their eyes, a willow branch broken into four sticks became their legs. The deities recited sacred prayers and songs as the Wind beings swept through and blew first breath into them. The deities, satisfied with their creation, sent them to earth upon a rainbow trail and we Navajo have been shepherds of our sacred sheep ever since.

This is the story of T’áá Dibé, the First Sheep. Note that in Diné culture, the rainbow signifies protection and brings blessings to the land because it is the link, the bridge, between the earth and the sky.

As a child, Navajo Nikyle Begay says, I was taught by many elders that we weave for moisture, we raise sheep for moisture. These sacred animals have a connection to the Universe. Their hooves awaken Mother Earth’s energy. Their calls awaken Father Sky. We must recite our prayers. Sing to and for your sheep, sing as you weave, sing to bring harmony. Do this proudly, so you’re heard by the Diyiin Dine’e – The Deities. Collect the sacred plants as you’re out with the sheep, use those plants with your prayers. And smoke their tobacco, let the smoke carry your prayers into the beyond. Show the Universe that as a five-fingered being, you appreciate the moisture, that you appreciate the sheep.

Diné be'iiná Inc. Director Aretta Begay says: We feel everything is connected. The sheep is our food, it's what we eat, and what we wear. It's part of our ritual, our healing and our survival. (First Nations Development Institute)

The Diné people's relationship with sheep is the cornerstone of their cultural identity and intergenerational knowledge. The annual "Sheep is Life" celebration brings the Navajo nation together to honor the sheep, their production, and their use through traditional foods, procedures, and storytelling.

The philosophy of "Sheep Is Life" reveals that sheep are viewed as conscious beings actively involved in relationship-building with Diné people. Sheep are not merely a source of food, but are respected as sentient beings with their own agency. Diné shepherds still sing to their flocks and protect them from predators. When they have to kill one of them for meat, they do it quickly and with dignity, and the entire family shows its gratitude for the gift of life that is given each time it takes an animal for food. This relationship underscores their pivotal role in Diné intellectual and social life, even in death.

Navajo shepherds and sheep, U.S. postcard from 1911. Source: Navajo Sheep Project.

Shearing sheep, obtaining wool to be used in Navajo Indian rug weaving, 1933. Source: Arizona State Museum.

LEFT: Navajo girls spin and card wool, probably in New Mexico. First half of the 20th century. Source: Denver Digital Library, Special Collections, [call number X-33047], CO, USA.

RIGHT: Navajo weaver, probably in New Mexico. First half of the 20th century. Source: Denver Digital Library, Special Collections, [call number X-33049], CO, USA.

LEFT: Hedipa, a Navajo Woman. Photo by John K. Hillers, ca. 1880. Source: Smithsonian American Art Museum, Renwick Gallery, USA.

RIGHT: Studio portrait of Judge Klah, a Navajo judge of Justice of the Peace. He poses with his two wives among beautiful woven blankets. Photo by William M. Pennington, 1900-1938. Source: Denver Digital Library, Special Collections, [call number X-32969], CO, USA.

Navajo-Churro sheep play a vital role in ceremonial practices.

Sheep with four horns are believed to have more spiritual power. When the Navajo people conduct healing or blessing ceremonies, they prefer Churro sheep, specifically those with four horns, because they are perceived to have more strength to contribute to the rituals.

The Navajo people consider the consumption of mutton sacred. They believe that Churro sheep are sacred, and that eating them is a great privilege and honor.

Diné people are taught to maintain spiritual connections through practices such as:

- Singing to and for their sheep;

- Singing while weaving;

- Singing to bring harmony;

- Reciting prayers that can be heard by the Diyiin Dine'e (the gods);

- Collecting sacred plants while out with the sheep;

- Using tobacco smoke to carry prayers "to the other side".

Navajo weaver Tahnibah Natani says: So when you are weaving, actually you're doing a prayer because the warp is considered a representation of rain. The tension cord is lightening. The top of the beam of the loom, the very top, represents the sky, Father Sky. And the bottom bar represents Mother Earth. Everything on the loom has a special song for it. So it becomes a prayer. (Hal Cannon)

The weaving tradition is deeply intertwined with spiritual beliefs:

- According to Diné tradition, Spider Woman provided songs, techniques, and prayers for weaving, while Spider Man built the first looms.

- Weaving is not just a practical craft but "an important expression of artistic creativity and spiritualism."

- Elders teach that "we weave for moisture, we raise sheep for moisture" - connecting these practices to cosmic forces.

- The sheep's hooves are believed to " awaken the energy of Mother Earth," while their calls "awaken Father Sky."

Spider Woman instructed the Navojo women how to weave on a loom which Spider Man told them how to make. The crosspoles were made of sky

and earth cords, the warp sticks of sun rays, the healds [heddles] of rock crystal and sheet lightning. The batten was a sun halo, white shell made the comb. There were four spindles: one a stick of zigzag lightning with a whorl of cannel coal; one a stick of flash lightning with a whorl of turquoise; a third had a stock of sheet lightning with a whorl of abalone; a rain streamer formed the stick of the south, and its whorl was white shell. (Kahlenberg and Berlant 1972; Strawn and Littrell, 2007)

The Navajo Churro sheep exemplifies the holistic Diné worldview in which spiritual beliefs, economic activities, artistic expression, and daily life are inseparable. As described in scholarly literature, Diné philosophy, spirituality, art, and sheep are interwoven like wool in the strongest weave. This interweaving represents a sophisticated indigenous knowledge system that recognizes the interrelationships between humans, animals, and the spiritual world.

Now it is easy to understand not only the economic damage, but also the cultural vandalism and spiritual injury caused by U.S. military campaigns and government policies.

When one considers the historical, sacred, and ecological value of the Navajo Churro, it also becomes clearer why these sheep embody Diné self-determination, sovereignty, heritage, and identity.

Navajo Secrets 2018 Annual Sheep Shearing by Marissa Neal

The Navajo Churro Sheep Ceremony Video by Western Folklife Center

For more info about the work of Coen Engelhard: https://coenengelhard.com/2018/01/31/film-ende/

Framing the Finale: A Reflective Overture

The Navajo Churro Sheep are the result of a respectful, non-violent, and wise interaction between humans, animals, and a land that often refuses to rain. These sheep constitute a "local breed". Local sheep breeds typically have unique genetic characteristics that make them well suited to their native regions, such as disease resistance, hardiness, or particular wool or meat qualities. They often represent important cultural heritage and agricultural biodiversity. In addition to the Navajo-Churro of the American Southwest, examples include the Herdwick sheep of England's Lake District and the Manech of the Basque Country. However, the modern approach taken by the U.S. government and agencies throughout most of the 20th century has favored the hyper-productivity of non-native breeds or hybrids based solely on financial considerations. This approach has denied the value of the genetic diversity of a local breed such as the Navajo Churro and deliberately ignored its cultural value. In short, the pursuit of monetary profit has attempted to swallow like a juggernaut the non-monetary wealth associated with both biological and cultural diversity. «During the twentieth century, Westernized agricultural practices reversed the emphasis on local breeds. Instead, agricultural methods promoted a small number of high-performance (improved) breeds considered superior for greater production of meat and wool within controlled environments (Heise and Christman 1989; Sponenberg and Bixby 2000). These marketing strategies encouraged raising a few improved breeds and threatened the survival of such local breeds as the Navajo-Churro.» (Strawn and Littrell, 2007)

The forced hybridization of the Navajo Churro sheep has its perfect counterpart in the forced assimilation of the Navajo people in the first half of the 20th century. They are interrelated chapters in a broader history of federal policy toward Native Americans during this period.

U.S. government interference with Navajo sheep occurred in several phases, beginning with the initial destruction in 1863 by Kit Carson's troops. After the 1868 Treaty of Bosque Redondo allowed the Navajo to return to their homeland, the U.S. government provided replacement sheep, but these were foreign breeds that contaminated the pure Churro bloodlines. The U.S. government considered certain Navajo Churro traits undesirable, particularly their slow growth and inability to gain fat quickly (though these were valuable adaptations for survival in the desert). Government officials made a concerted effort to get Native communities to switch to what they considered "more desirable" breeds to maximize meat production. The most devastating blow came in the 1930s, as we've seen, when the Bureau of Indian Affairs implemented the Navajo Livestock Reduction Program, ostensibly to prevent soil erosion. This program resulted in the slaughter of tens of thousands of Churro sheep and pushed the breed to the brink of extinction.

On the other hand, the federal government's attempts to assimilate the Navajo people were part of a broader policy aimed at all Native Americans. The government established Indian boarding schools that children were required to attend. In these institutions, staff forced students to cut their hair and wear uniforms; prohibited them from speaking their native language; punished displays of Native culture with beatings, withholding food, or forced labor; and forced them to convert to Christianity.

The government also banned traditional religious ceremonies and implemented policies designed to replace tribal traditions with mainstream American cultural values.

The Dawes Act of 1887 allotted tribal lands to individuals in exchange for U.S. citizenship and the surrender of tribal self-government, resulting in the transfer of approximately 93 million acres from Native American control. The Indian Citizenship Act of 1924 granted citizenship to all Indians living on reservations as part of the assimilation strategy. The Indian Reorganization Act of 1934 attempted to replace assimilation programs with tribal empowerment initiatives. However, the Navajo Nation rejected this act because of distrust of the Bureau of Indian Affairs after the devastating livestock reduction program of 1934.

The combination of these policies-removing children from their communities, banning religious practices, forcing land redistribution, and destroying traditional livelihoods through livestock reduction-created profound cultural trauma and economic hardship for the Navajo people.

The parallel between the forced hybridization of Navajo-Churro sheep and the forced assimilation of the Navajo (Diné) people provides a profound case study of the consequences of destroying biological, genetic, and cultural diversity.

This case illustrates how «Language, religions and knowledge diversities and the environment diversities have been intimately related thoughout human history. However, it is only in our era of globalization, on the light of the continuing process of extinction of cultural and biological diversity, that natural and social sciences have increased their attention on the complex and diverse phenomena of the human relationship with the environment. The growing recognition of the commonalities and the interlinkages of these dual realms of diversity and the fact that the breakdown of these connections underlies many of the environmental and social problems humanity is facing, have let to frame a new field called "biocultural diversity", which is defined as the total variety exhibited by the world's natural and cultural systems.» (Maiero and Shen, 2004)

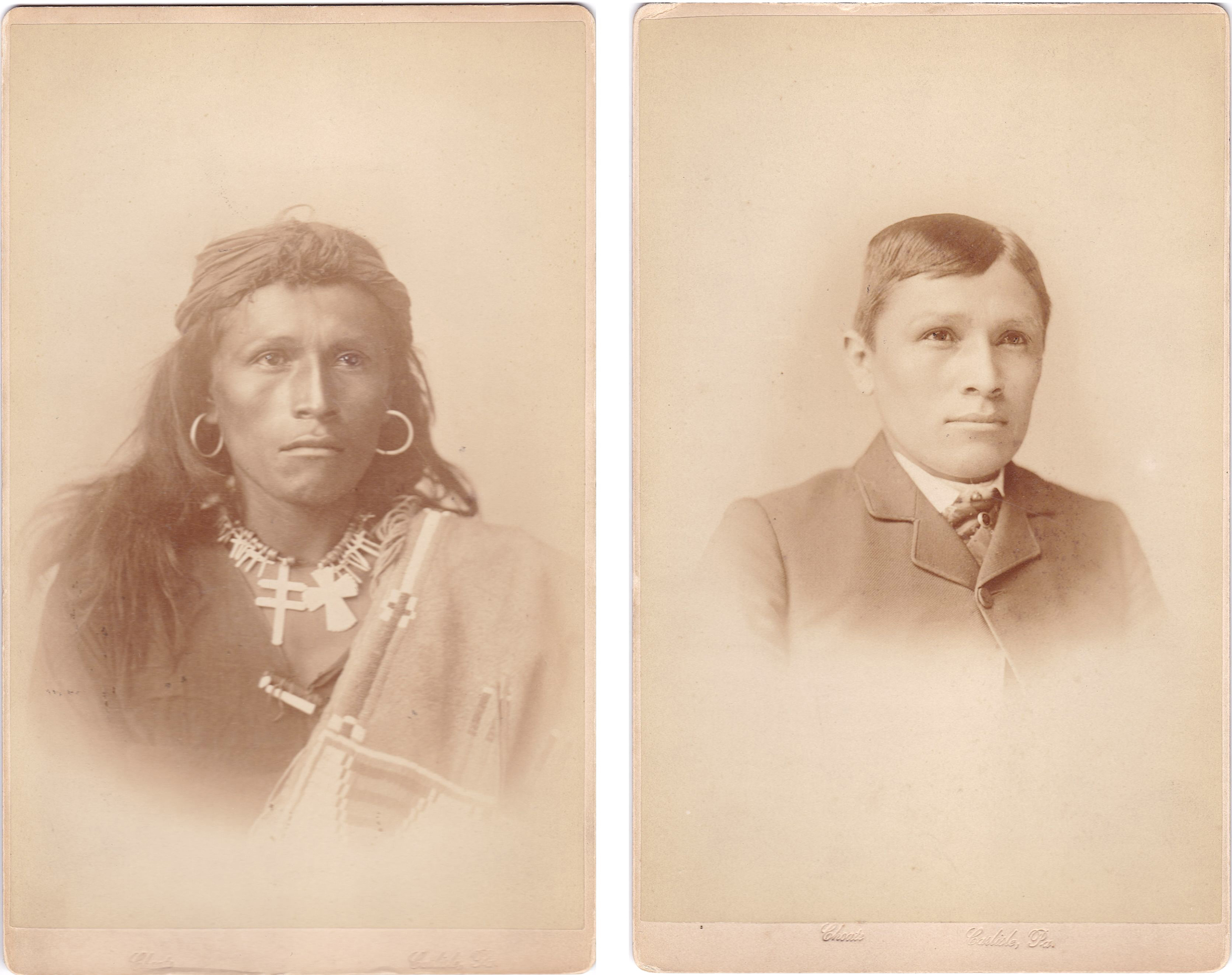

Tom Torlino, a member of the Navajo Nation, entered the Carlisle Indian Industrial School on October 21, 1882 and departed on August 28, 1886. These "before and after" photographs were taken by the school staff: between them there are only 3 years and a half. Source: Carlisle Indian School Digital Resource Center. The Carlisle Indian Industrial School was a federally funded boarding school in Carlisle, Pennsylvania, that operated from 1879 to 1918. Its mission was to assimilate Native American children into mainstream American culture.

When government officials targeted the Churro sheep for elimination, they simultaneously attacked a keystone of Diné cultural identity. Allow me to underscore three critical aspects.

First, the elimination of "unimproved" sheep breeds not only reflects a utilitarian approach that privileges immediate economic productivity over other values, including adaptation to local conditions and cultural significance, but more radically it exemplifies an approach in which the search for short-term monetary gain takes precedence over all other economic considerations, precluding a priori the possibility of sustainable development for land, people, and animals. Diné elders poetically insisted that the land became chronically degraded only after depletion angered the Holy People who controlled the rain. This perspective challenges Western scientific frameworks while offering alternative approaches to understanding ecological relationships. From this perspective, many indigenous cultures have valuable lessons to teach today's experts.

Second, we need to reassess what "progress" and "improvement" should mean in the 21st century. The U.S. government's livestock program was motivated by the belief that it was "doing good by bringing progress and modern range management to an unenlightened people". This raises the question of who defines progress and improvement. Who has claimed the right to do so? Can those who have arrogated to themselves the right to do so continue to do so for all of us? The logic of survival of the fittest and the logic of maximum profit with minimum short term effort are bringing humanity to the brink of an abyss. It's time to listen to different voices and build a different way together.

Third. Today, as global biodiversity faces unprecedented threats and indigenous cultures continue to struggle against homogenizing forces, this historical case offers a crucial lesson: preserving both biological and cultural diversity requires recognizing their interdependence. The destruction of the Navajo-Churro sheep and the forced assimilation of the Diné illustrate that «fostering the health and vigour of ecosystem is one and the same goal as fostering the health and vigour of human societies, their cultures, and their languages.» (Maiero and Shen, 2004)

This understanding challenges us not only to develop more holistic inclusive approaches to both environmental and cultural conservation that respect indigenous sovereignty and knowledge systems, but also to understand that the protection of biodiversity and any conservation effort that is limited to the "green" field is doomed to failure.

La ecología sin lucha social es simplemente jardinería, "ecology without social struggle is simply gardening", as Chico Mendes or perhaps Eduardo Galeano (attribution uncertain) said. I wrote it talking of the struggle of the Guna people in their own land (Kuna Molas of San Blas part 2). I'm saying it now: any protection of biocultural diversity must involve political action and moral choices to be effective. Using vague terms like "eco-friendly," "natural," or "green" and selling any kind of product under these labels is pure "greenwashing," a highly deceptive marketing practice. Drawing a green earth on one's cheeks and shouting "green" slogans is performative activism without substantive action and impact. Saving water, buying responsibly, and separating garbage for recycling are laudable small actions that carry great risk: focusing exclusively on small individual actions can distract from necessary systemic changes in industry, policy, and infrastructure.

Navajo Prayer by Anil Thapa

Anil Thapa is an artist, author and student of Himalayan, shamanic and native wisdom traditions. Influenced from a young age by the Hindu and Buddhist culture of his native Nepal, Anil practiced and honed his skills as a devoted Thankgka artist.

D.P. Sponenberg and C. Taylor, Navajo-Churro sheep and wool in the United States, in "Animal Genetic Resources Information", 2009, 45, 99–105. © Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, 2009.

Susan M. Strawn (Colorado State University), Restoring Navajo-Churro Sheep: Acculturation and Adaptation of a Traditional Fiber Resource, Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings, 2004.

Susan M. Strawn and Marya Littrell, Returning Navajo Churro Sheep for Navajo Weaving, in "Textile", Volume 5, Issue 3, pp, 300-319; 2007, Berg, United Kingdom

Hal Cannon, Sacred Sheep Revive Navajo Tradition, For Now, June 13, 2010, NPR.

Marina Maiero and Xiaomeng Shen, Commonalities between Cultural and Bio-Diversity, ZEF Bonn (Center for Development Research of the University of Bonn), 2004.

Alyx Becerra

OUR SERVICES

DO YOU NEED ANY HELP?

Did you inherit from your aunt a tribal mask, a stool, a vase, a rug, an ethnic item you don’t know what it is?

Did you find in a trunk an ethnic mysterious item you don’t even know how to describe?

Would you like to know if it’s worth something or is a worthless souvenir?

Would you like to know what it is exactly and if / how / where you might sell it?